Atypical Headaches

/So the patient has a headache. How can one risk stratify them into primary or secondary causes? Patients with a secondary cause of their headache will often present with signs or symptoms that will aid in their diagnosis. There are symptoms that are classically referred to as the "red flag symptoms" that, if present, are suggestive of secondary causes of headaches and can be remembered by the SNOOP2 mnemonic: [3]

Systemic symptoms: fever, chills, weight loss, HIV+, immunocompromised, or history of cancer

Neurologic symptoms: confusion, change in mental status, vision change, seizure, asymmetric reflexes

Onset: acute, sudden, or "thunderclap"

Older patient: >50 years old with new-onset or progressive headache

Previous headache history: first headache or change in character, severity, or frequency

Pregnant or postpartum

It is important to remember that patients presenting any "red flag symptom" require thorough workup and assessment, even if their symptoms are alleviated. [4]

Giant Cell Arteritis

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a chronic inflammatory disease involving large and medium-sized arteries in patients older than 50 years old that typically presents with headaches and is associated with the feared complication of vision loss.

Annual incidence of 20 per 100,000 at risk

More common in females than males (2-3:1). [5]

Virtually never presents in patients younger than 50 years old and peaks in incidence in the 7th decade of life. [6]

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of GCA is incompletely understood. The most common associated condition with GCA is polymyalgia rheumatica, with 30-50% of patients with biopsy diagnosed GCA having an underlying history of polymyalgia rheumatica.

Arterial wall remodeling and intimal hyperplasia occur as a result of CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages, which frequently undergo granulomatous organization with the formation of giant cells.

Of note, the term "temporal arteritis" has fallen out of favor as it undermines the involvement of other vessels involved, such as the aortic arch and the branches of the carotid arteries. [6]

Clinical Presentation [7]

Headache (30-80%)

Fever (20-50%)

Scalp/temporal artery tenderness (30-70%)

Jaw pain/claudication (30-70%)

Monocular or binocular vision loss (12-40%).

Workup

The definitive diagnosis of GCA is not made in the ED as the gold standard diagnostic is a temporal artery biopsy. However, using a combination of physical exam findings, symptoms, and blood work can support the diagnosis.

Lab tests/imaging:

CBC, CMP, ESR, CRP, UA

Consider

CXR (to exclude alternative diagnosis)

ECG (evaluate for coronary involvement)

Although most patients will have a markedly elevated ESR or CRP (89.8% in one study); other studies have shown that 24% of biopsy-proven GCA had a normal ESR. Thus, ESR and CRP are imperfect markers of GCA; additionally, if they are normal, GCA is not excluded. [9]

1990 Criteria for the Classification of Giant Cell Arteritis Established by the American College of Rheumatology

Age ≥50 years at disease onset

New headache (new in onset or type of pain)

Temporal artery abnormality (tenderness to palpation or decreased pulsation, unrelated to atherosclerosis of cervical arteries)

Elevated ESR ≥50 mm/h

Abnormal temporal artery biopsy

*When 3 of the 5 above criteria are met, a diagnosis of GCA is made with a sensitivity of 93.5% and specificity of 91.2%* [8]

Ultrasound and MRI of the temporal artery have not become the standard of care but are currently being studied as a means of diagnosis.

Management

**The treatment of suspected GCA should never be deferred until a temporal artery biopsy is performed, as delay in treatment may result in permanent vision loss. Glucocorticoids are the mainstay of treatment and should be initiated as soon as GCA is strongly suspected**

Patients without vision changes: Prednisone 40-60 mg/day or 1 mg/kg/day (max 60 mg/day) for 2-4 weeks, followed by a taper.

Patients with vision changes: Methylprednisolone 1000 mg/day for 3 days, followed by Prednisone 1mg/kg/day (max 60mg) for 2-4 weeks [10]

In certain circumstances, such as significant premorbid conditions (uncontrolled DM, osteoporosis and morbid obesity), consideration should be made glucocorticoid sparing strategies.

Tocilizumab [12]

Methotrexate [13]

Aspirin - Unless there is an absolute contraindication, patients should receive 81 mg ASA daily to reduce the risk of cardiovascular, ocular, and cerebral events. [10]

All patients should receive urgent ophthalmology consultation as well as PCP and Rheumatology follow-up.

Acute Angle Closure Glaucoma (AACG)

AACG is an eye and vision threatening disease characterized by narrowing or closure of the anterior chamber angle, and is often associated with a headache. [14]

Glaucoma is the second-leading cause of blindness in the world.

Nearly 70 million people in the world between the ages of 40-80 years suffer from acute angle glaucoma. [15]

Pathophysiology

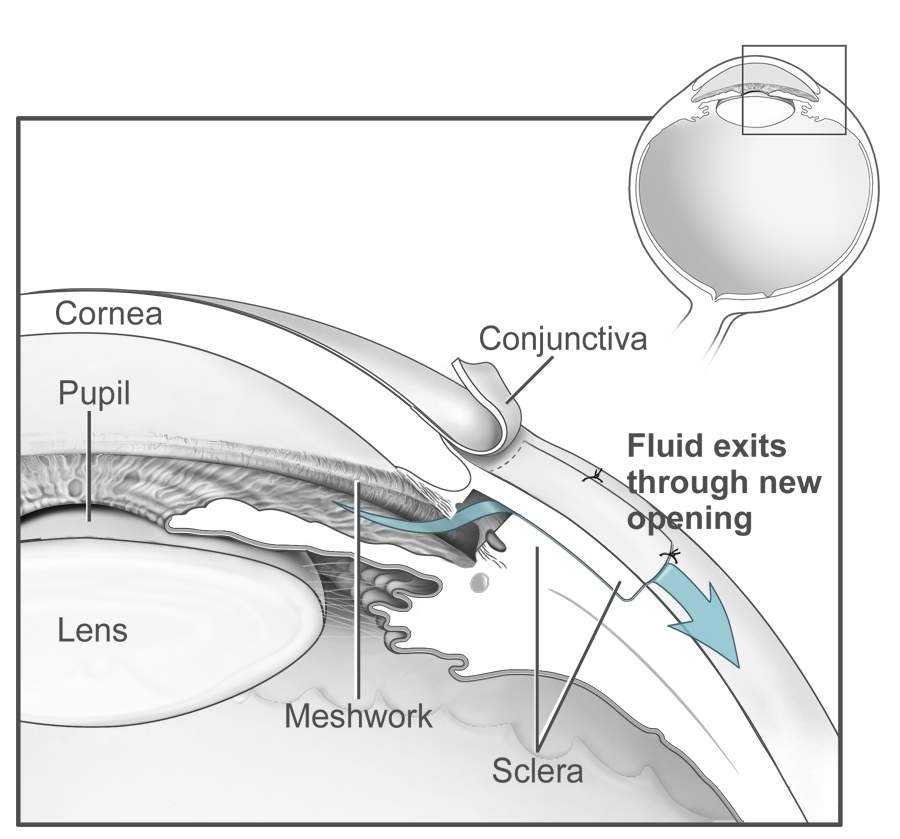

Aqueous humor flows from the ciliary body through the pupil to reach the anterior chamber and exits the eye.

Intraocular pressure is the result of the balance of production and drainage of aqueous humor.

Pupillary block occurs when the pupillary margin blocks the passage of aqueous from the posterior chamber to the anterior chamber.

The resulting rapid elevation of intraocular pressure results in pain and may cause decreased vision.

Clinical Presentation [16]

Jonathan Trobe, M.D., CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Headache

Blurred vision

Monocular, red eye

“Halos” around lights

Nausea and vomiting

Workup

The physical exam is the best diagnostic tool for correctly identifying AAGC and may demonstrate any of the following:

Monocular red, painful eye

Asymmetric mid-dilated pupil that is sluggish or non-reactive to light

IOP >30 mm Hg (often >40)

Optic nerve cupping

Consider BMP as medication management may vary depending on renal function and electrolytes.

There is no role for radiographic studies in the diagnosis of AACG.

Management [17]

http://www.nei.nih.gov/photo/eyedis/index.asp, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ophthalmology, if available, should be immediately consulted for concern of AACG. However, delay in treatment (>1hr) should not be made prior to ophthalmology evaluation, and empiric treatment should be administered.

Goal is to alleviate symptoms by reducing IOP and can be accomplished by taking the following actions and administering the below medications and taking the following actions:

Emergent Ophthalmology Consultation

Recheck IOP q30-60 minutes

Elevate head of bed to decrease IOP

Place patient in well lit room

Start the following medications:

1 drop Topical B-blocker (eg. Timolol 0.5%) q30min x 2

1 drop Alpha-2 agonist (eg. Brimonidine 0.1%)

1 drop Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (Dorzolamide 2%)*

Acetazolamide 250-500 mg IV or 250 mg x 2 PO (1 time after first round of eye drops)

*Separate administration of ophthalmic agents by ≥1 minute.

If IOP is still elevated despite above treatments, repeat topical agents and administer Mannitol 1-2 g/kg IV over 45 min (contraindicated in CHF, renal disease and intracranial hemorrhage)

Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension (IIH)

IIH is a disorder that characterized by increased ICP associated with headache and visual change, with no identifiable cause of increased ICP on imaging or CSF studies.

1 case per 100,000 per year, though frequency is increasing with the obesity epidemic

Primarily affects women of childbearing age with obesity.

Pathophysiology

Increased production or decreased absorption of the CSF.

Presentation [19]

Headache (84%) - worse upon wakening

Visual Changes (70%) -transient

Double vision (~33%)

Back pain (~60%)

Neck pain (41%)

Tinnitus (60%)

Papilledema- hallmark finding, typically bilateral and symmetric and there is a direct correlation with degree of papilledema and vision loss.

6th nerve palsy

If papilledema is discovered, the following must be performed:

Visual acuity check

Formal visual fields check

Dilated fundoscopy

Measure BP to exclude malignant hypertension (SBP>180/DBP>120)

Workup

If papilledema is present, imaging is necessary:

Head MRI w/ contrast - preferred

Head CT w/ contrast - if MRI not available

CT/MRI Venogram (rule out CVST)

Ophthalmology consultation

CSF studies

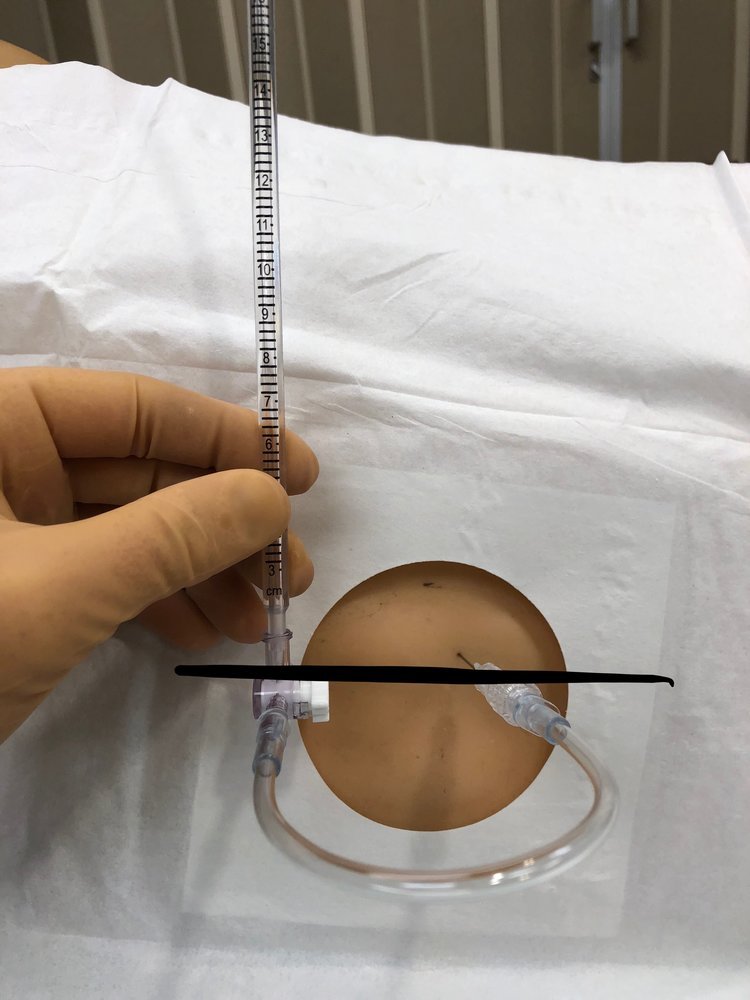

Perform LP in left lateral decubitus and obtain opening pressures

Opening pressure >250 mm = increased ICP

Send CSF for glucose, protein, cell count and culture

Normal in IIH

Management

Short Term: Treatment goal is to alleviate headache and preserve vision.

Patients with sudden visual decline need surgical consultation for potential VP shunt.

IV steroids

Serial LP’s

Long term: Prevent recurrence of headaches

Weight loss, salt and fluid restriction

Acetazolamide (250-500 mg BID)

+/- Topiramate or Furosemide

Patients with a known diagnosis of IIH with an exacerbation of headache without red flag symptoms (SNOOP2) or papilledema do not need neuroimaging or repeat lumbar puncture. [19]

Trigeminal Neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is characterized by recurrent brief episodes of unilateral electric shock-like pains, abrupt in onset and termination, in the distribution of one or more divisions of the fifth cranial (trigeminal) nerve that typically are triggered by innocuous stimuli [20-21]

Annual incidence of 4-13 per 100,000 people

Affects females > males (1:1.5-1:1.7)

Pathophysiology

Compression of the trigeminal nerve by an aberrant loop of artery or vein is the main mechanism of TN (80-90%), however a small portion of cases result from multiple sclerosis or brainstem lesions, such as schwannomas (10%).

Presentation [22]

Paroxysmal attacks of intense, sharp or stabbing, superficial pain in the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve.

Pain lasts 1-5 seconds

Associated with “trigger zones”, with light touch in these areas triggering an attack (chewing, talking, brushing teeth, cold air, smiling or grimacing)

May have autonomic symptoms such as lacrimation, conjunctival injection and rhinorrhea

A more mild, continuous pain between attacks is present in up to 1/2 of patients

Workup

The diagnosis of TN is clinical diagnosis, which can be made using the criteria listed below: [23]

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, Third Edition (ICHD-3) diagnostic criteria for TN

A. Recurrent paroxysms of unilateral facial pain in the distribution(s) of one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve, with no radiation beyond, and fulfilling criteria B and C

B. Pain has all of the following characteristics

Lasting from a fraction of a second to two minutes

Severe intensity

Electric shock-like, shooting, stabbing, or sharp in quality

C. Precipitated by innocuous stimuli within the affected trigeminal distribution

D. Not better accounted for by another ICHD-3 diagnosis

Once the diagnosis of TN is suspected on clinical grounds, a search for secondary causes should be undertaken. [24]

MRI w/ and w/o contrast

Head CT and CTA (if MRI not available)

Trigeminal reflex testing (rarely used)

Management

First line agents:

Carbamazepine - Starting dose: 100-200 mg BID, increasing by 200 mg daily as tolerated until sufficient pain relief (typical maintenance dose is 600-800 mg daily; max 1200 mg/day)

Oxcarbazepine - Starting dose: 300 mg BID, gradually increased by 300 every third day as tolerated until sufficient pain relief, till total dose of 1200-1800 mg/day.

** It is recommended patients are tested for HLA-B*15:02 prior to initiating to reduce risk of SJS/TEN (more common in Oxcarbazepine)

2nd line agents can be added to 1st line agents for patients unresponsive to treatment, or used as mono therapy in patients intolerant of or who have contraindications to first line agents: [25-27]

Gabapentin - 300-1200 mg TID (start with 300 mg QD, then increase by 300 QD until 1200 mg/day)

Lamotrigine - 400 mg QD (consult neurology for dosing as titration is complex)

Baclofen - 40-80 mg QD (start with 15 mg daily given over 3 doses, with gradual titration to 40-80 mg)

Botulinum toxin injections

Rescue therapy for confirmed TN patients presenting to the ED in pain: [28-30]

IV Lidocaine - 5mg/kg infusion over 1 hour has been shown to provide relief for up to 24 hours. Requires continuous cardiac monitoring and frequent BP checks.

IV Phenytoin or Fosphenytoin - 15mg/kg over 30-120 minutes (no more than 50 mg/minute )

SQ Sumatriptan - 3mg SQ followed by oral 50 mg qd x 7 days

Patients refractory to medical management should be considered for surgical intervention.

References

Edlow JA, Panagos PD, Godwin SA, Thomas TL, Decker WW; American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(4):407-436. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.001

Goldstein JN, Camargo CA Jr, Pelletier AJ, Edlow JA. Headache in United States emergency departments: demographics, workup and frequency of pathological diagnoses. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(6):684-690. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01093.x

Dodick DW. Pearls: headache. Semin Neurol. 2010;30(1):74-81. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1245000

Edlow JA, Panagos PD, Godwin SA, Thomas TL, Decker WW; American College of Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients presenting to the emergency department with acute headache. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;52(4):407-436. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.07.001

Hoffman GS. Giant cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):ITC65-ITC80.

Increase in age at onset of giant cell arteritis: a population-based study. AU Kermani TA, Rheum Dis. 2010 Apr;69(4):780-1. Epub 2009 Oct 22.

Smetana GW, Shmerling RH. Does this patient have temporal arteritis?. JAMA. 2002;287(1):92-101. doi:10.1001/jama.287.1.92

Sait MR, Lepore M, Kwasknicki, R, et al. The 2016 revised ACR criteria for diagnosis of giant cell arteritis - can this avoid unnecessary temporal artery biopsies? Int J Surg Open. 2017;9:19-23.

Kermani TA, Schmidt J, Crowson CS, et al. Utility of erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein for the diagnosis of giant cell arteritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2012;41(6):866-871.

Baig IF, Pascoe AR, Kini A, Lee AG. Giant cell arteritis: early diagnosis is key. Eye Brain. 2019;11:1-12. Published 2019 Jan 17. doi:10.2147/EB.S170388

Tocilizumab for induction and maintenance of remission in giant cell arteritis: A phase 2, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. AU Villiger PM, Adler S, Kuchen S, Wermelinger F, Dan D, Fiege V, Bütikofer L, Seitz M, Reichenbach S

2021 American College of Rheumatology/Vasculitis Foundation Guideline for the Management of Giant Cell Arteritis and Takayasu Arteritis. Maz M, et al.

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of adjuvant methotrexate treatment for giant cell arteritis. AU Hoffman GS,

Primary Angle Closure Preferred Practice Pattern(®) Guidelines. Prum BE, Jr, Herndon LW Jr, Moroi SE, Mansberger SL, Stein JD, Lim MC, Rosenberg LF, Gedde SJ, Williams RD

Bonomi L, Marchini G, Marraffa M, et al. Epidemiology of angle-closure glaucoma: prevalence, clinical types, and association with peripheral anterior chamber depth in the Egna-Neumarket Glaucoma Study. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(5):998-1003.

Bagheri N, Wajda B, Calvo C, et al. The Wills Eye Manual, Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016.

Jackson J, Carr LW III, Fisch BM, et al. Care of the Patient with Primary Angle Closure Glaucoma: Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline. St. Louis, MO: American Optometric Association

Guluma, K., & Lee, J. E. (2018). Ophthalmology. In Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice (9th ed.). Philadephia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders.

Mollan SP, Hornby C, Mitchell J, Sinclair AJ. Evaluation and management of adult idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(6):485-488. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2018-002009

Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Love S, Coakham HB Brain. 2001;124(Pt 12):2347.

Neuropathic pain in the general population: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. van Hecke O, Austin SK, Khan RA, Smith BH, Torrance N Pain. 2014;155(4):654. Epub 2013 Nov 26.

Trigeminal neuralgia--a prospective systematic study of clinical characteristics in 158 patients. Maarbjerg S, Gozalov A, Olesen J, Bendtsen L Headache. 2014 Nov;54(10):1574-82. Epub 2014 Sep 18.

Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition.

Practice parameter: the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the European Federation of Neurological Societies. Gronseth G, Cruccu G, Alksne J, Argoff C, Brainin M, Burchiel K, Nurmikko T, Zakrzewska JM Neurology. 2008;71(15):1183.

Efficacy and Safety of Gabapentin vs. Carbamazepine in the Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Meta-Analysis.Yuan M, Zhou HY, Xiao ZL, Wang W, Li XL, Chen SJ, Yin XP, Xu LJ Pain Pract. 2016;16(8):1083. Epub 2016 Feb 19.

Clinical effectiveness of lamotrigine and plasma levels in essential and symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia. Lunardi G, Leandri M, Albano C, Cultrera S, Fracassi M, Rubino V, Favale E Neurology. 1997;48(6):1714.

Baclofen in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: double-blind study and long-term follow-up.Fromm GH, Terrence CF, Chattha AS Ann Neurol. 1984;15(3):240.

The Effect of Intravenous Lidocaine on Trigeminal Neuralgia: A Randomized Double Blind Placebo Controlled Trial.Stavropoulou E, Argyra E, Zis P, Vadalouca A, Siafaka SRN Pain. 2014;2014:853826. Epub 2014 Mar 10

Treatment of refractory trigeminal neuralgia with intravenous phenytoin.Tate R, Rubin LM, Krajewski KC Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68(21):2059

Sumatriptan alleviates pain in patients with trigeminal neuralgia.Kanai A, Suzuki A, Osawa S, Hoka S Clin J Pain. 2006;22(8):677.

Authorship

Written by Casey Glenn, MD

Dr. Glenn is a PGY-1 University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine