Mastering Minor Care: Orbital Infections

/Setting the scene

You sign up for “eye problem” on the board and you walk in the room. You think the eye might be infected… but now what? Do you treat them with antibiotics? Do nothing? Call ophthalmology?

Let’s take a closer look and see just what you need to focus in on your H&P so you can triage and appropriately manage the most common eye infections you might see walk into the ED.

Anatomy of the Eye

Before you put the page out to ophthalmology, let’s review the anatomy of the eye to make sure that your differential and management is appropriately tailored to each patient.

Anatomy Figure 1: Courtesy of course hero module 8 nervous system, under http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/us/ with additional sinus structures drawn by hand

Surrounding Structures on the face (anatomy figure 1)

Frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinuses surround the orbit

Lacrimal glands in the superolateral corner of each eye produce tears which drain medially into the nasolacrimal gland

Orbital septum: membrane connecting from the periosteum of the orbital rim to the upper and lower eyelids

The eyelids are lined with hair follicles and various secretory glands

Valveless superior and inferior ophthalmic veins drain directly into the cavernous sinus

The eye itself can be divided into its superficial structures, layers, as well as various spaces and chambers.

Superficial Structures (anatomy figure 2)

Conjunctiva: loose connective tissue covering the eye and posterior eyelids, highly vascular

Cornea: covers the anterior aspect of the eye

Sclera: the whites of the eye, covers the posterior aspect of the eye, attachment site for extraocular muscles

Anatomy Figure 2: courtesy of the university of melbourne cornea research under creative commons license 3.0

Layers (anatomy figure 2)

Fibrous layer: the outermost layer of the eye made up of the sclera and the cornea (a bulge in the sclera in the front of the eye), has the function of protecting the inside of the eye like skin protects the inside of the body

Vascular Layer: called the “uvea” and consists of the iris, ciliary body, and choroid; main function is to supply blood and nutrients to the eye, but the iris and ciliary body also help with lens accommodation for proper vision

Neural Layer: consists of photoreceptor cells which make up a layer called the retina, contains the fovea (center of vision or the macula), connects to the optic disc at the back of the eye

Chambers (anatomy figure 2)

Anatomy Figure 3: Courtesy of Sight specialists at https://www.sightspecialists.com.au/dry-eye-disease/#. Accessed 7/9/2023. licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 with additional structures drawn by hand

Anterior Chamber: between the cornea and iris, part of the anterior SEGMENT of the eye, filled with aqueous humor secreted by the ciliary body

Posterior Chamber: a small space between the iris and lens, also part of the anterior SEGMENT of the eye, involved in the production of aqueous humor for the anterior chamber

Vitreous chamber: between the lens and the posterior eye wall and optic nerve, makes up the posterior SEGMENT of the eye, is the largest of the three chambers, filled with vitreous humor or fluid to support the structure of the eye and allow for proper light filtering to the retina

“Spaces” (anatomy figure 3)

Don’t forget that another important concept is the pre-septal space vs the post-septal space, which is divided by the orbital septum. Knowing these spaces can be helpful when differentiating peri-orbital vs orbital cellulitis.

Eye Pathology

Now let’s dive back into some common eye disease processes you may see on a typical day in the emergency department. They are arranged by anatomical location of disease process, starting with surrounding eye structures diseases, superficial structure diseases, and anterior chamber diseases. We do not discuss the posterior chamber in this blog post.

Disease processes involving surrounding structures of the eye

CASE 1

A patient presents with an itchy and burning feeling on their eyelids. They notice some crusting on their eyelids, particularly in the morning. They may have a PMHx of atopic dermatitis, rosacea, or eczema. On exam you notice some flaky crusting at the base of the eyelashes and possibly mild inflammation or thickening of the eyelids themselves.

-

Blepharitis

-

Although this process is not always infectious, it can be caused by S. aureus.

-

1) Eyelid hygiene with warm compresses and gentle scrubbing with baby shampoo

2) If conjunctiva have associated inflammation, could consider topical antibiotics such as erythromycin ointment

3) Follow up with ophthalmology within 1 week

CASE 2

A patient presents with complaints of a painful bump on or around their eyelid. They state that it started as a small bump but over the last few days has gotten bigger and redder and is very painful. On exam, they have an erythematous and tender nodule isolated to the margins of the eyelid.

-

A hordeolum (or a stye)

-

Usually these develop after the small glands that line the eyelid get plugged. Frequently, patients have a history of chronic blepharitis. Similar to blepharitis, they are also often caused by S. aureus. Usually these form on the outer part of the eyelid, but can sometimes form on the inner part of the eyelid.

-

1) Supportive care with warm compresses, usually resolve within 1 week without intervention

2) Referral to ophthalmology for incision and drainage if not resolved within 1-2 weeks or causing significant discomfort to patient

CASE 3

A patient presents with complaints of swelling between their nose and left eye, that has been ongoing for a few days with slowly worsening discomfort. They also feel like they have noticed some discharge intermittently in the affected eye. On exam, they have a swollen and erythematous area starting at the medial canthus of the eye and extending inferiorly towards the bridge of the nose.

-

Dacrocystitis

-

This is caused by obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct which often leads to inflammation and infection of the attached lacrimal sac. Pressure over the lacrimal sac may often express purulent material through the medial canthus, allowing for culture. Most often this is caused by gram positive organisms such as S. aureus, S. pneumo, and H. flu but can in some cases be caused by Pseudomonas.

-

In infants, this can represent a medical emergency as it can quickly lead to orbital cellulitis and sepsis. Hospitalization and emergent ophthalmology consultation are warranted, in addition to IV broad spectrum antibiotics.

In adults, treatment consists of massages with warm compresses and treatment with antibiotics to cover MRSA. Adults can safely follow up with ophthalmology within 1-2 days.

Of note, most kids above age 1 can be treated similar to adults, assuming normal course of infection, normal vaccination status, and no known history of immunocompromise otherwise.

CASE 4

A patient presents with a few days of progressively worsening swelling and discomfort of their upper eyelid. They are not sure if it hurts more with eye movement, but do notice some slightly blurred vision. They deny fevers. On exam, you notice swelling and erythema to the upper eyelid, with normal extra ocular movements and normal conjunctiva. Patient’s visual acuity is also normal.

-

Likely peri-orbital (or pre-septal) cellulitis

-

The orbital septum is a thin fibrous membrane that forms a barrier between the superficial eyelids and the structures of the orbit itself.

Peri-orbital cellulitis is an infection of the superficial eyelids. On exam, there will be no pain with extra ocular movements, and general no complaints of ophthalmoplegia or diplopia.

Orbital cellulitis is when infection spreads into the orbit itself, and often starts first as pre-septal cellulitis. Patients will have a history of a few days of eyelid swelling and discomfort followed by worsening pain including pain with extra ocular movements and a “deeper” pain of the eye itself. Patients will often have objective visual acuity impairment as well as a fever or leukocytosis.

-

1) If only peri-orbital cellulitis is considered, oral antibiotics for “skin” bacteria can be prescribed and patient can be discharged. patients should follow up with ophthalmology within a few days.

2) If orbital cellulitis is a consideration based on red flags on history or exam, obtain CT imaging (CT maxillofacial with IV contrast) and consult ophthalmology in the emergency department as patient may require admission with IV antibiotics.

Disease processes involving superficial structures of the eye

CASE 1

A patient presents with redness of the eye associated with discharge for the last few days. When they wake up in the morning, they notice their eye feels “stuck shut” and they have to clean the crusted discharge off to open it. They also feel as if their vision is a bit blurry.

-

Conjunctivitis

-

Viral conjunctivitis is characterized by conjunctival injection, watery discharge, and usually associated with a viral prodrome 1-2 days prior

Bacterial conjunctivitis is also characterized by conjunctival injection but has a more purulent thick discharge and there is often not a viral prodrome prior.

-

Whether viral or bacterial, these are usually self-limited infections that only require supportive care (i.e. saline eyedrops for “burning” or “gritty” feeling of discomfort.

1) Consider topical antibiotics such as erythromycin ointment or polymyxin eye drops for more severe symptoms

2) Perform fluorescein exam to rule out corneal abrasions and ulcerations

3) No ophthalmology required unless significant corneal involvement found

4) If history suggests STD such as gonorrhea, consider empiric topical and systemic treatment for gonorrhea and consult ophthalmology in the emergency department as these infections have a higher risk of corneal ulceration and perforation

CASE 2

A patient presents with severe pain and eye redness that developed over the last day. They note some sensitivity to bright lights, and on exam are wearing sunglasses. When removed, you note significant conjunctival injection with a hazy opacity over the corneal surface.

-

Bacterial keratitis, also known as a corneal ulcer

-

These often start as traumatic corneal abrasions that, untreated, become secondarily infected causing corneal ulcers. Contact lens wearers are at increased risk for this process.

Corneal ulcers are most frequently caused by Pseudomonas (especially if they wear contact lens), as well as S. aureus, S. pneumo, and mycobacterium.

-

1) Fluorescein exam is key in diagnosis and must be performed in all patients

2) Prescribe topical fluoroquinolone eye drops such as moxifloxacin

3) Discontinue contact lens usage

4) If ulcer is > 2 mm or directly in the visual axis (middle of cornea), emergent ophthalmology consult in the emergency department is warranted. otherwise, patient can follow up with ophthalmology within 1-2 days for repeat exam.

CASE 3

A patient presents with pain on their forehead and around / in their eye. Symptoms began as mild eye irritation a few days ago, and rapidly progressed to pain and redness. They report blurred vision as well as photophobia and redness / watery discharge of the eye. They have recently been under a lot of stress due to family problems that they do not want to elaborate on. On exam you note conjunctival injection and skin lesions, some of which appear vesicular, on the forehead and around the orbit.

-

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus or ocular shingles

-

A “Hutchinson sign” - or vesicular lesion(s) on the tip of the nose indicates a 2-3-fold increase in the risk of ocular involvement.

However, patients with ANY lesions on the the face in the ophthalmic distribution of the trigeminal nerve - including but not limited to the tip of the nose - should prompt a full eye examination and ophthalmology consultation in the emergency department.

-

1) Treatment with topical gancyclovir

2) Systemic treatment with oral acyclovir or valacyclovir

3) Consultation of ophthalmology in the emergency department as patients require very close follow up

4) Consideration of topical steroids such as prednisolone acetate for patients with more severe corneal lesions. This helps prevent long term corneal scarring and other complications which unfortunately can be fairly common in this disease process.

CASE 4

A 50 year old female presents with mild blurry vision and watery discharge of her eye for the last several weeks. Over the last few days she feels like it has progressed with worsening blurry vision and discharge, as well as new eye redness. She does endorse eye discomfort, but states it is not frankly painful. She has recently been under a lot of stress due to taking care of her elderly parents. On exam, you note conjunctival injection and a small amount of watery discharge.

-

The presentation of “red eye” is fairly common in the emergency department. Because this patient endorses some discomfort, the ddx is very broad, and should include conjunctivitis (viral, bacterial, and allergic), keratitis, scleritis, episcleritis, corneal abrasion or ulceration, uveitis. Severe etiologies such as acute angle closure glaucoma or optic neuritis are less likely as the patient only endorses mild discomfort and not severe pain.

-

As with all red eye presentations you should perform a visual acuity, tonopen pressure check, fluorescein exam, as well as a slit lamp examination. If these do not reveal any abnormal findings, then you can safely rule out most dangerous etiologies of red eye, especially if the patient has no pain.

However, on this patient the Woods lamp exam with fluoresceine is KEY in making the diagnosis. You note classic dendritic or “tree branching” lesions, consistent with viral keratitis, most likely HSV keratitis. Corneal scrapings (performed by ophthalmology) can be used to confirm a diagnosis.

-

The most common cause of viral keratitis with dendritic lesions is HSV-1, representing approximately 50% of the cases. Approximately 1.5 million cases occur yearly, with 40,000 resulting in severe permanent visual impairment. HSV keratitis can occur as a primary infection or as part of a reactivation syndrome precipitated by stress or underlying illness.

-

Similar to zoster ophthalmicus described in case 3, treatment involves topic ganciclovir, as well as oral anti-virals such as acyclovir or valacyclovir in patients with more severe disease.

Patients with mild disease can follow up with ophthalmology within a few days, but more diffuse lesions should prompt an ophthalmology consultation in the emergency department.

Disease processes involving the anterior segment of the eye

CASE 1

A patient presents with a complaint of a red and painful eye associated with blurry vision. On exam, you note an odd shaped pupil and conjunctival injection. The patient reports intolerance of any light being shined in their eye during exam. Pupils are appropriately reactive despite pain with this exam.

-

For the patient with a painful eye, you should consider uveitis, acute angle closure glaucoma, optic neuritis, or orbital cellulitis. There are other possibilities but these are the most common.

-

Given the history, you should have a high suspicion for uveitis.

Physical exam will reveal conjunctival injection with ciliary flush (this is a ring of red or violet conjunctival and episcleral blood vessels spreading out from the cornea with decreased inflammation farther from the cornea). This differs from simple conjunctivitis which has a more even distribution of inflammation. Occasionally in uveitis, you will see oddly shaped pupils due to the uvea’s involvement with pupillary shape.

Fluorescein exam will likely be unremarkable, but slit lamp exam will reveal classic “cell and flare”.

If you would like to learn more about uveitis, please visit our blog post dedicated to this topic at https://www.tamingthesru.com/blog/bread-butter-em/uveitis where you will also find images of “cell and flare” listed above.

-

Uveitis is defined as inflammation of the uvea, which consists of the iris, ciliary body, and / or choroid.

The most common cause is idiopathic, but all infectious, inflammatory, and traumatic processes should be considered. Frequent causes include HSV, HIV, VZV, TB, CMV, Syphilis, Sarcoidosis, IBD, ankylosing spondylitis, Bechet’s disease, multiple sclerosis, JIA, Kawasaki’s disease, toxoplasmosis.

-

1) Appropriate work up in conjunction with emergency ophthalmology consultation. work up often includes labs for HIV, RPR, HLA-B27, and imaging such as a CXR for TB

2) Treatment of presumed cause from work up

3) Topical steroids such as prednisolone acetate 1% to reduce inflammation and / or cyclopentolate eye drops to reduce pain from ciliary spasm

CASE 2

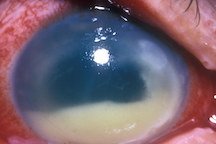

An elderly female presents with complaints of a red eye with discharge noted. She is also concerned as she cannot see anything other than blurry shapes out of that eye. She reports routine outpatient cataract surgery in the same eye about 8 days ago. On exam, you see a cloudy cornea with surrounding conjunctival injection, and a white layer of fluid overlying the bottom of the cornea. Patient’s visual acuity from that eye is 20/200.

-

Endophthalmitis, which is an infection of the vitreous and aqueous intraocular fluids.

-

1) Exogenously, meaning bacteria or fungi gets into the eye from outside the body. This most often happens due to an eye surgery, although can also happen after traumatic injuries to the eye such as puncture wounds.

2) Endogenously, meaning bacteria spreads from an infection in another part of the body such as a UTI or meningitis. Common risk factors for endogenous spread include immunocompromise, diabetes, malignancy, IV drug use, endocarditis, or chronic steroid use.

-

1) This is a true ophthalmologic emergency. consult ophthalmology immediately.

2) Patient will require admission to the hospital and injection of antibiotics or antifungals directly into the eye, also known as intra-vitreal antibiotics.

3) Patients may require drainage of infection in the OR through a surgery known as a vitrectomy.

CASE 3

A patient presents with a sudden onset unilateral headache behind their right eye. They had just finished watching a movie in the theater and noticed onset of headache while watching the movie that progressed to a severe headache by the end of the movie. They also report blurry vision and weird “circles” that they see when looking at lights. They are holding an emesis bag. On exam, you note a fixed and dilated pupil with a hazy cornea and associated conjunctival injection.

-

Acute angle closure glaucoma, which is an acute obstruction of aqueous humor at the outflow tract in the anterior chamber causing a rapid increase in intra-ocular pressure.

-

Ocular pressure testing with intra-ocular pressures > 30 mmHg in the right clinical context are essentially diagnostic for acute angle closure glaucoma. Pupil of the affected eye must also be mid-dilated and non-reactive as part of the diagnosis.

-

1) Consult ophthalmology - this is ophthalmologic emergency!

2) Rapidly reduce intra ocular pressure with appropriate medications.

-topical beta blocker eye drops (timolol 0.5%) to reduce aqueous humor production

-topical muscarinic agonist eye drops (pilocarpine 1-2%) to decrease pupil size and facilitate an increase in aqueous humor outflow. only works at intra-ocular pressures < 40 mmHg

-topical alpha 2 agonist eye drops (brimonidine 0.15%) to increase trabecular outflow

-topical steroid eye drops (prednisolone 1%) to decrease inflammation and scar formation

-systemic IV acetazolamide (500 mg) to reduce aqueous humor production

-systemic IV mannitol (1-2 g / kg) to draw fluid out of the vitreous humor by osmotic pressure

Conclusion

When approaching a patient with an “eye problem”, it’s easy to become overwhelmed by the breadth of potential diagnoses that need to be considered. Asking yourself a few key questions in addition to your standard history will help you narrow your differential and guide your approach to diagnosis and treatment. Is the eye painful or painless? Has their vision been affected; if so, how?

Additionally, physical exam is key in clinching the diagnosis. Try to think through and identify which structures or chambers of the eye are affected. Be sure to use the slit lamp if there is concern for corneal or scleral disruption and remember that eye issues might be due to structures surrounding the orbit as opposed to within the orbit itself.

With this approach in mind, you should feel confident triaging and managing some of the more common eye complaints that you’ll encounter in the ED.

Post by Bronwyn Finney, MD and Rachel Haupt

Dr. Finney is a PGY-4 and Chief Resident in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati and Mastering Minor Care Section Editor

Rachel Haupt is a 4th year medical student at the University of Cincinnati Medical Center with intentions to apply to EM residencies this application cycle.

Editing by James Li, MD and Anita goel, md

Dr. Li is an Assistant Professor at the Washington University of St. Louis in Emergency Medicine and a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2021.

Dr. Goel is an Assistant Professor at the University of Cincinnati and a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2018.

References

Azari, Amir A., and Neal P. Barney. "Conjunctivitis." Jama 310.16 (2013): 1721. Web.

Silverman, Michael A., and Barry E. Brenner."Acute Conjunctivitis.": Overview, Clinical Evaluation, Bacterial Conjunctivitis. Web. 15 Jan. 2016

American Academy of Ophthalmology. Preferred Practice Pattern: Blepharitis. October 2012 revision. Available at: http://one.aao.org/preferred-practice-pattern/blepharitis-ppp--2013. Accessed November 10, 2014.

O’Brien TP. The role of bacteria in blepharitis. Ocul Surf 2009;7(2 suppl):S21-2

Silkiss, RZ, Paap, MK, Ugradar, S, The Association between Mask Wear and Chalazion Formation during the Covid-19 Pandemic, AJO Case Reports, 2020.

Taylor RS, Ashurst JV. Dacryocystitis. [Updated 2019 Mar 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470565/

Pinar-Sueiro S, Sota M, Lerchundi TX, Gibelalde A, Berasategui B, Vilar B, et al. Dacryocystitis: Systematic Approach to Diagnosis and Therapy. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2012 Jan 29.

Watts P. Preseptal and orbital cellulitis in children: a review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012; 22(1): 1-8

Sweeney A.R., Yen M.T. (2020) Eyelid Infections. In: Albert D., Miller J., Azar D., Young L. (eds) Albert and Jakobiec's Principles and Practice of Ophthalmology. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-90495-5_75-1

Walls, R. M., Hockberger, R. M., & Gausche-Hill, M. (2018). Rosen's Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical practice (9th ed., Vol. 1 & 2). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier.

Bae C, Bourget D. Periorbital Cellulitis. [Updated 2022 Jul 18]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470408/

Bragg KJ, Le PH, Le JK. Hordeolum. [Updated 2022 Aug 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441985/

Phelps, Paul O., Ringisen, Alexander L., Yen, Michael T, and Burkat, Cat N. “Vasculature of orbit.” AAO: EyeWiki. Web. Available at: https://eyewiki.aao.org/Vasculature_of_Orbit#:~:text=the%20external%20carotid.-,Orbital%20Veins,fissure%20into%20the%20cavernous%20sinus.

“Eye: Anatomy.” Lecturio. Web. Available at: https://app.lecturio.com/#/article/3896?return=__app__%2Fsearch%2Fconcepts%2Feye%2520anatomy

Duplechain A, Conrady CD, Patel BC, et al. Uveitis. [Updated 2023 Apr 3]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540993/

Khazaeni B, Khazaeni L. Acute Closed Angle Glaucoma. [Updated 2023 Jan 2]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430857/

Vicky S.K Chen, Jonathan Hsi-Dar Penm. “Management of Eye Disorders and the Pharmacist's Role: Eye Infections.” Encyclopedia of Pharmacy Practice and Clinical Pharmacy. Elsevier,2019,Pages 580-597. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-812735-3.00538-0.

Welder JD, Kitzmann AS, Wagoner MD. “Herpes Simplex Keratitis”, EyeRounds.org; 31 Dec 2012. Available from: https://eyerounds.org/cases/160-hsv.htm

Adams S, Knight D. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus. JETem. 3(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.21980/J88H07

Romito K and Husney A. “Eye anatomy and function”, MyHealth.Alberta.ca; 24 Jan 2022. Available from: https://myhealth.alberta.ca/Health/Pages/conditions.aspx?hwid=hw121946#hw121946-Credits

“Eye Anatomy”, Exeter Eye; 26 Jun 2023. Available from: https://www.exetereye.co.uk/the-eye/eye-anatomy/#:~:text=The%20iris%20is%20the%20colored,posterior%20chambers%20of%20the%20eye

Yiallouros M. “Anatomy and function of the eye”, KinderKrebsInfo.de; 21 Nov 2016. Available from: https://kinderkrebsinfo.de/doi/e182894

Boyd K and McKinney JK. “What is Uveitis?”, American Academy of Ophthalmology; 8 Dec 2022. Available from: https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-uveitis

MAnasco C, McIntosh B, Koyfman A, Long B. “Approach to the Red Eye”, emDocs; 31 Aug 2020. Available from: http://www.emdocs.net/approach-to-the-red-eye/

Weiner G. “Demystifying the Ocular Herpes Simplex Virus”, EyeNet Magazine; Jan 2013. Available from: https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/demystifying-ocular-herpes-simplex-virus

Langridge C, Williams D, Koyfman A, Long B. “Acute angle closure glaucoma: ED relevant management”, emDocs; 10 Feb 2017. Available from: http://www.emdocs.net/acute-angle-closure-glaucoma-ed-relevant-management/

Mukamal R, DeAngelis KD, Turbert D. “What is Endophthalmitis?”, American Academy of Ophthalmology;27 Oct 2022. Available from: https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/what-is-endophthalmitis

Purcell M, Conroy MJ, Koyfman A, Bright J. “Endophthalmitis Highlights”, emDocs; 12 Jan 2016. Available from: http://www.emdocs.net/endophthalmitis/