Opioid Withdrawal Therapy: Autonomic Hypersensitivity Tamed

/Introduction

Image 1: Summarizes the mechanism, recognition, and treatment of OWS

Opioid withdrawal is a common presenting complaint in the emergency department. As opioid use disorder prevalence continues to increase, opioid withdrawal will continue to increase as well. Opioid withdrawal is a debilitating condition resulting from the discontinuation of opioid use in a person that has developed dependence following chronic use of opioid (1). Patients with opioid withdrawal commonly present with symptoms of autonomic hypersensitivity including restlessness, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. On physical examination providers will appreciate mydriasis, yawning, diaphoresis, increased bowel sounds, and piloerection. It is important to recognize the signs and symptoms of opioid withdrawal quickly to minimize time to treatment to provide patients with much needed comfort.

Mechanism of withdrawal

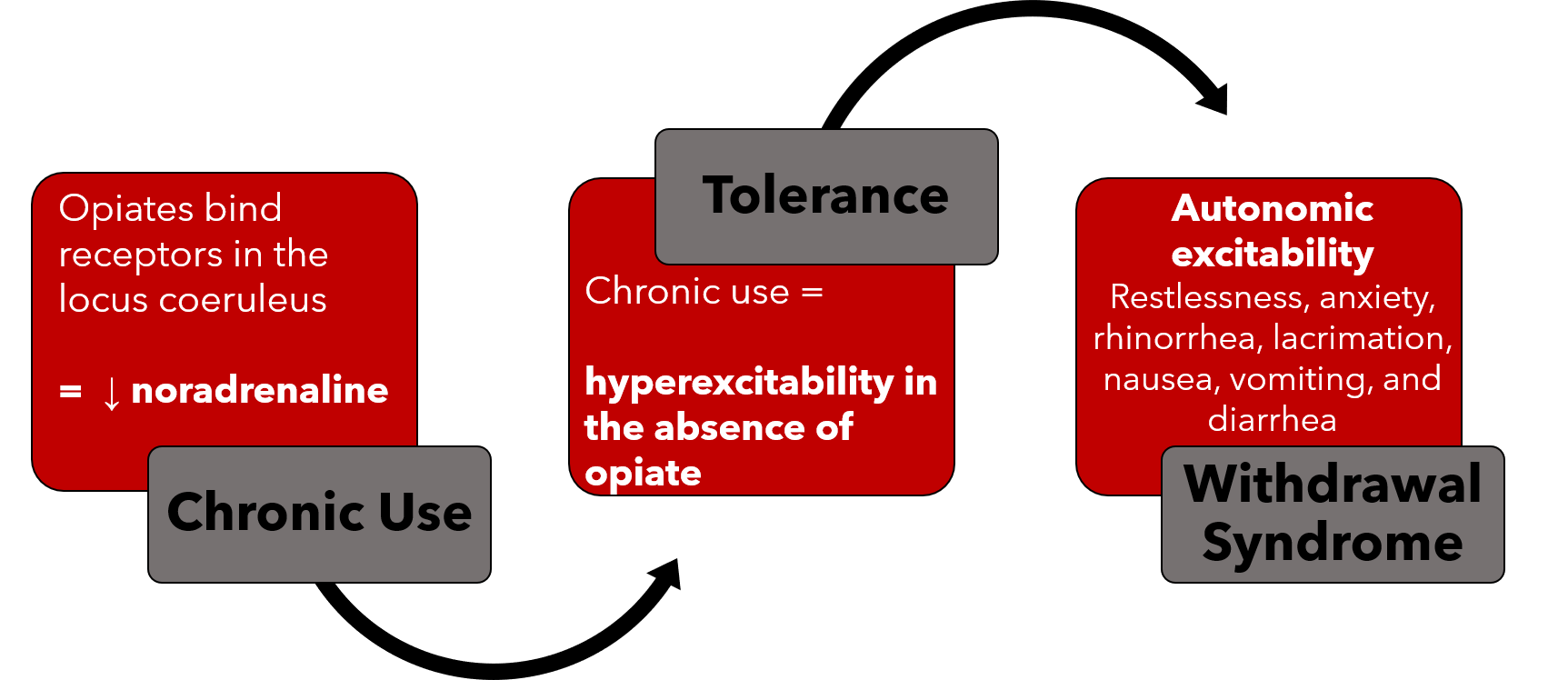

The mechanisms behind opioid dependence and withdrawal are complex. Opioid receptors are G-protein coupled receptors that inhibit cAMP in various tissues resulting in decreased neuronal activation in these tissues. One key location of these receptors is the locus coeruleus, an area of the brain responsible for noradrenergic innervation of the limbic system, cerebral cortex, and cerebellar cortex. When opioid are present, they bind to receptors in the locus coeruleus leading to decreased noradrenaline release and dampened adrenergic tone (1-3).

In patients who chronically use opioid, there is compensatory change in expression of proteins within the opioid receptor which leads to excitability of neurons in the locus coeruleus in the absence of opioid binding (2,3). With discontinuation of opioid use in this population, the increased excitability of these neurons leads to increased noradrenaline release and results in signs and symptoms of autonomic hypersensitivity in the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, and gastrointestinal tract.

Image 2: Summarizes the Mechanism for OWS

Severity of withdrawal is directly related to the dose, duration, and continuity of opioid use (4). WIthdrawal can also be precipitated by the administration of partial opioid agonists, like buprenorphine, or opioid antagonists, including naloxone or naltrexone (1). These medications bind the opioid receptors with increased affinity and precipitate symptoms of withdrawal. Withdrawal secondary to iatrogenic administration opioid partial agonists or antagonists is often more severe due to the sudden increase in noradrenaline release. Physicians must be careful in assessing recent opioid use prior to administration of these medications.

Recognizing opioid withdrawal

It is important to recognize opioid withdrawal in order to facilitate symptom relief for our patients. Opioid withdrawal is a very distressing constellation of symptoms including restlessness, anxiety, rhinorrhea, lacrimation, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea. On a physical exam you may appreciate mydriasis, yawning, diaphoresis, increased bowel sounds, and piloerection.

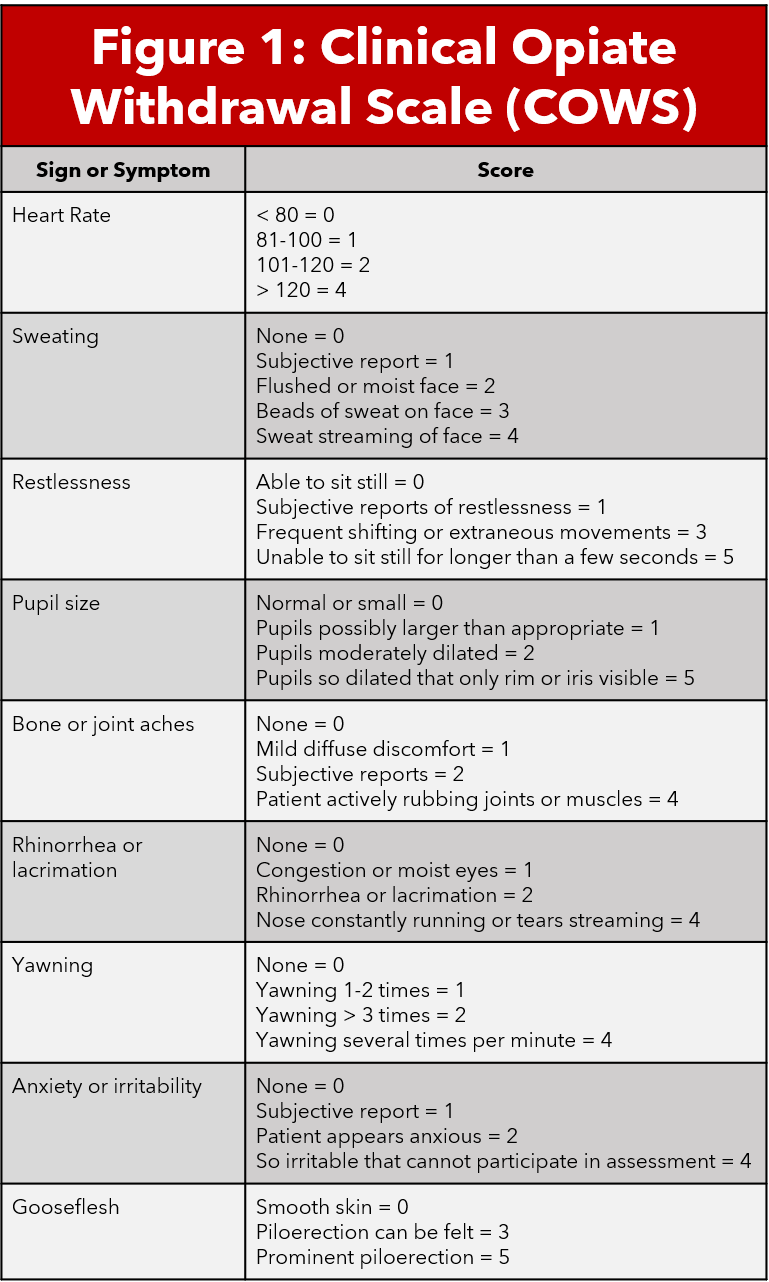

The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Score (COWS) is a validated scale that combines objective physical exam findings and patient subjective assessment of their symptoms to determine the severity of their withdrawal. COWS is an eleven question survey on a 4 point likert scale. Scores less than 5 indicate no withdrawal, 5-12 mild withdrawal, 13-24 moderate withdrawal, and greater than 25 severe withdrawal (5,6). Calculating a COWS score is an important step in determining severity of withdrawal and therefore candidacy for treatment.

Evidence based medicine

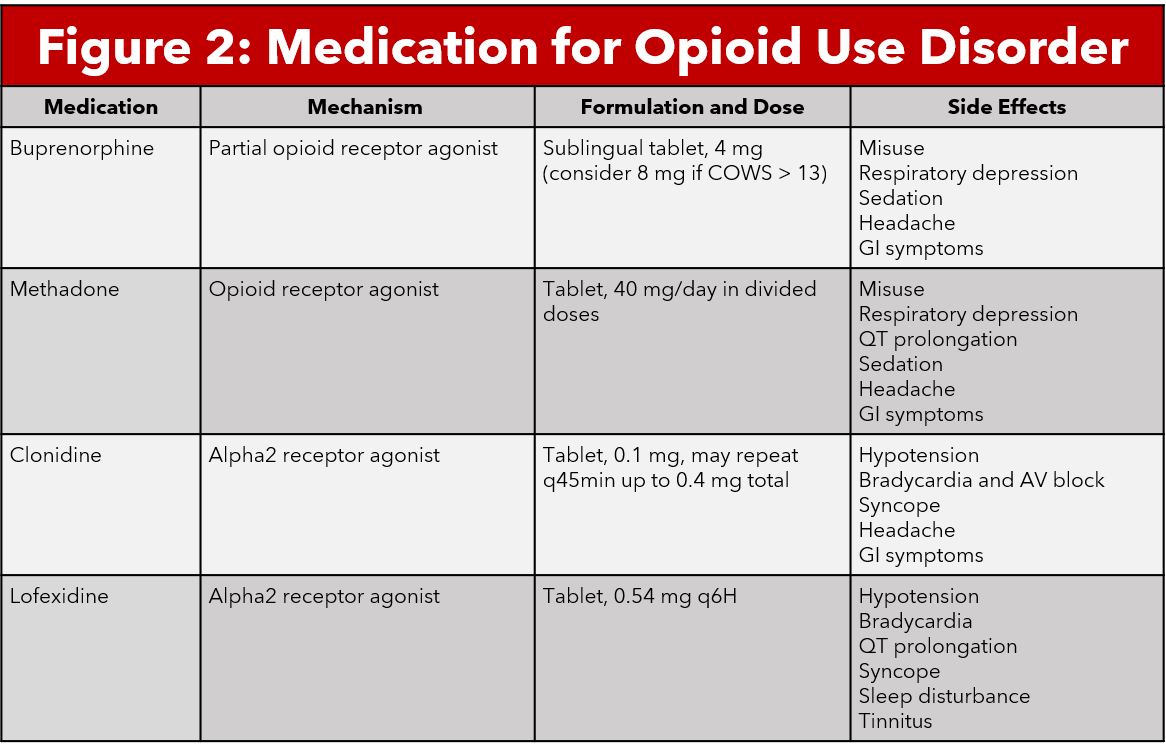

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is a partial opioid agonist that binds to mu opioid receptors with high affinity. Buprenorphine time to peak action is 30-60 minutes and has a duration of action up to 72 hours for high doses. Buprenorphine has also been shown to cause less respiratory depression and sedation compared to other opioid medications (7, 4). These qualities make this medication a good candidate for treatment of opioid withdrawal symptoms. The medication most commonly comes in the form of a sublingual tablet. Given that buprenorphine has such a high affinity, clinicians should not administer the medication within 24 hours of opioid use as this may precipitate withdrawal (7).The use of buprenorphine in the emergency department is indicated in patients with COWS > 7 (5,6).

A 2017 Cochrane Review involving 27 studies and 3,408 patients compared the use of buprenorphine for opioid withdrawal compared to other interventions including methadone, alpha2-adrenergic agonists, symptomatic management, or placebo. The Cochrane review found that buprenorphine was more effective than alpha2-agonists in ameliorating the intensity of opioid withdrawal, increasing the duration of treatment, and minimizing adverse effects. Retention in and completion of treatment was notably higher in the buprenorphine group, likely secondary to the lesser side effect profile. Buprenorphine was equal to methadone in alleviating withdrawal symptoms with similar side effect profiles. There were no significant differences between the duration of treatment or amelioration of withdrawal symptoms between tapering strategies of buprenorphine for opioid withdrawal. Notably, few studies within the review examined different dose tapering therefore this should be further examined (8).

Methadone

Methadone is a synthetic opioid agonist that primarily binds to mu opioid receptors, including in the locus coeruleus (9). Methadone is used for opioid detoxification, opioid withdrawal therapy, and chronic pain management in certain populations. Methadone comes in both oral and intravenous forms, with a long half life and duration of action of approximately 24 hours (9,10). Because methadone is an opioid agonist, it does carry the risk of respiratory depression in large doses or with concomitant comorbidities. Other adverse effects include somnolence, weight gain, sexual dysfunction, QTc prolongation and constipation. Providers should be aware that patients who use chronic methadone can develop tolerance and eventually dependence (10).

A 2013 Cochrane Review involving 23 randomized controlled trials and 2,467 patients compared methadone to any other pharmacologic treatment for the management of opioid withdrawal. Other pharmacologic treatments included other opioids, alpha2-adrenergic agonists, anxiolytics, an herbal supplement, and placebo. There was no significant difference between the groups on completion of treatment, number of participants abstinent at follow-up, severity of withdrawal symptoms, or adverse reactions (11). Notably, the later Going et. al Cochrane Review (2017) determined that buprenorphine and methadone were more effective than alpha2-agonists and symptomatic management at managing the severity of opioid withdrawal symptoms (8).

Alpha2-adrenergic: Clonidine and Lofexidine

Alpha2-agonists bind to multiple subtypes of alpha2 receptors found in various tissues throughout the body. Binding to the alpha2 receptor causes inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and reduces cAMP, causing hyperpolarization and decreased noradrenergic neurons and decreases release of noradrenaline in the locus coeruleus. This reduces the symptoms of autonomic hypersensitivity in opioid withdrawal (12). Several medications fall in this alpha2-agonist category including clonidine and lofexidine.. Clonidine is a medication used for the treatment of hypertension, anxiety, ADHD, chronic pain, and opioid withdrawal. Lofexidine is an alpha2-agonist that was recently FDA approved for use for opioid withdrawal in the United States in May 2018. Several studies have postulated that lofexidine causes less hypotension, therefore it may be the better choice for use in opioid withdrawal management (13-15).

A 2016 Cochrane Review involving 26 randomized controlled trials and 1,728 patients compared alpha2-agonists including clonidine, lofexidine, guanfacine, and tizanidine with methadone, symptomatic medications, or placebo. There was moderate evidence that alpha 2-agonists were more effective than placebo at reducing opioid withdrawal symptoms. Completion of therapy was also significantly more likely with alpha-2 agonists compared to placebo. Methadone appeared to decrease withdrawal severity compared to alpha2-agonists, however this difference was insignificant. Alpha2-agonists were found to have more adverse events compared to methadone and placebo, with hypotension being the primary adverse effect experiences. Lofexidine was much less likely to result in hypotension compared to clonidine (13).

A 2017 double blind randomized controlled trial was completed as an FDA registration trial to study the safety and efficacy for lofexidine in opioid withdrawal therapy. This study included 264 patients who had established opioid dependence. The patients were randomized to receive either lofexidine or placebo for management of opioid withdrawal symptoms. Lofexidine was found to significantly decrease opioid withdrawal scores compared to placebo. Participants in the lofexidine group also remained in the study longer than those with placebo (14). A follow up 2019 multicenter, double blind, randomized placebo controlled study was also completed to examine the use of two different doses of lofexidine for opioid withdrawal symptoms compared to placebo. The study included 603 participants from 18 different centers in the United States. Both doses of lofexidine were found to significantly decrease opioid withdrawal symptoms compared to the placebo (15).

Naloxone prescriptions at discharge

While naloxone is not a medication that treats withdrawal symptoms, it is important for clinicians to consider providing naloxone prescriptions at discharge to reverse potentially life threatening overdose after leaving the hospital. Naloxone is an opioid antagonist with high affinity for the opioid receptor. Given this high affinity, naloxone will displace any opioids bound to receptors after administration. This results in rapid reversal of respiratory and CNS depression in patients following opioid overdose (16, 17). This mechanism can also result in precipitated withdrawal after administration. Naloxone is available in intravenous, intramuscular, and intranasal formulations, although the most common home prescription naloxone is the intranasal formulation.

A 2018 systematic literature review examined all existing literature related to naloxone distribution in emergency departments. Of the studies examined, it was determined that the emergency department may be a good opportunity to provide naloxone prescriptions and education for people at risk for overdose. These studies also commented on many barriers to providing naloxone prescriptions, therefore further efforts must be made to assist in implementation of naloxone administration programs in the emergency department (18). One retrospective cohort study has been completed since the publication of this systematic review which examined 291 overdose encounters in the emergency department. Almost three quarters of these patients were given naloxone on discharge. The authors did not find a significant difference between those who did and did not receive naloxone in repeat hospitalizations or death (17). Still, there are several states that require high risk patients to be co-prescribed naloxone along with opioid prescriptions, as is the case in Ohio.

University of Cincinnati Emergency Department Protocols

The University of Cincinnati Medical Center Emergency Department has a protocol for managing patients with opioid withdrawal. First, patients should be educated on Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) with the assistance of our Early Intervention Program (EIP). All patients with substance use disorder should receive an EIP consult. If the patient does not have interest in MOUD, you should treat the patient symptomatically using clonidine for restlessness, naproxen for pain, and ondansetron for nausea control. If the patient is interested in MOUD, assess the severity of their withdrawal by using COWS. If they have a score of 8 or greater, administer 4 mg sublingual buprenorphine. After administration, observe the patient for about an hour prior to recalculating their COWS score. If it remains elevated, continue to administer 4 mg buprenorphine every hour with a maximum total dose of 16mg. If the patient’s symptoms resolve and they are deemed appropriate for discharge, provide the patient with a prescription for naloxone and refer the patient to outpatient resources per EIP instructions. It is very important that these patients have timely follow up in order to continue MOUD and facilitate sobriety.

AUTHORED BY Bailee Stark, MD (@baileestark)

Dr. Stark is a first-year Emergency Medicine resident at the University of Cincinnati.

Reviewed, Edited, and POST BY ADAM GOTTULA, MD (@LAERTEZZ) & Ryan Lafollette, MD (@Lafoller)

Dr. Gottula is a fourth-year Emergency Medicine resident at the University of Cincinnati and future Anesthesia Critical Care Fellow at The University of Michigan with an interest in critical care and HEMS.

Dr. LaFollette is an Assistant Professor and Assistant Program Director at the University of CincinnatiEmergency Medicine Residency Program.

References

Shah M, Huecker MR. Opioid Withdrawal. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526012/

Nestler EJ. Under siege: The brain on opiates. Neuron. 1996;16(5):897-900. doi:10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80110-5

Burma NE, Kwok CH, Trang T. Therapies and mechanisms of opioid withdrawal. Pain Manag. 2017;7(6):455-459. doi:10.2217/pmt-2017-0028

Herring AA, Perrone J, Nelson LS. Managing Opioid Withdrawal in the Emergency Department With Buprenorphine. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73(5):481-487. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.11.032

Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(2):253-259. doi:10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007

Tompkins DA, Bigelow GE, Harrison JA, Johnson RE, Fudala PJ, Strain EC. Concurrent validation of the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) and single-item indices against the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment (CINA) opioid withdrawal instrument. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105(1-2):154-159. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.001

Cisewski DH, Santos C, Koyfman A, Long B. Approach to buprenorphine use for opioid withdrawal treatment in the emergency setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(1):143-150. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.013

Gowing L, Ali R, White JM, Mbewe D. Buprenorphine for managing opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD002025. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002025.pub5

Anderson IB, Kearney TE. Use of methadone. West J Med. 2000;172(1):43-46.

Brown R, Kraus C, Fleming M, Reddy S. Methadone: applied pharmacology and use as adjunctive treatment in chronic pain. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80(949):654-659. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.022988

Amato L, Davoli M, Minozzi S, Ferroni E, Ali R, Ferri M. Methadone at tapered doses for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003409.pub4

Gorodetzky CW, Walsh SL, Martin PR, Saxon AJ, Gullo KL, Biswas K. A phase III, randomized, multi-center, double blind, placebo controlled study of safety and efficacy of lofexidine for relief of symptoms in individuals undergoing inpatient opioid withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;176:79-88. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.02.020

Gowing L, Farrell M, Ali R, White JM. Alpha₂-adrenergic agonists for the management of opioid withdrawal. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD002024. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002024.pub5

Gorodetzky CW, Walsh SL, Martin PR, Saxon AJ, Gullo KL, Biswas K. A phase III, randomized, multi-center, double blind, placebo controlled study of safety and efficacy of lofexidine for relief of symptoms in individuals undergoing inpatient opioid withdrawal. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;176:79-88. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.02.020

Fishman M, Tirado C, Alam D, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Lofexidine for Medically Managed Opioid Withdrawal: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J Addict Med. 2019;13(3):169-176. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000474

Kaucher KA, Acquisto NM, Broderick KB. Emergency department naloxone rescue kit dispensing and patient follow-up. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(8):1503-1504. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.020

Papp J, Vallabhaneni M, Morales A, Schrock JW. Take -home naloxone rescue kits following heroin overdose in the emergency department to prevent opioid overdose related repeat emergency department visits, hospitalization and death- a pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):957. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4734-5

Gunn AH, Smothers ZPW, Schramm-Sapyta N, Freiermuth CE, MacEachern M, Muzyk AJ. The Emergency Department as an Opportunity for Naloxone Distribution. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(6):1036-1042. doi:10.5811/westjem.2018.8.38829