All that Pukes: Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome, Gastroparesis and More

/Feeling sick? Let’s make it quick!

Nausea and vomiting is one of the most frequently encountered complaints in the emergency department. Regardless of etiology, management should include addressing complications, such as dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, and ruling out life-threatening diagnoses.

Gastroparesis is delayed gastric emptying in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Management is centered around prokinetic agents to improve GI motility, as well as antiemetics and IV fluid administration to treat the nonspecific symptoms of nausea and vomiting

Haloperidol is increasingly used in the ED to treat the symptoms of gastroparesis and has been found to decrease rates of hospitalization and analgesic administration

Cyclic vomiting syndrome is characterized by stereotypical episodes of nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain with intervening periods of normal or baseline health in between. Management focuses on 1.) Trigger avoidance and prophylaxis 2.) Abortive therapies 3.) Supportive treatment

Differentiating between cyclic vomiting syndrome and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome involves stopping marijuana usage for at least one week. If symptoms improve or resolve, cannabis hyperemesis is likely

Capsaicin cream has been shown to decrease abdominal pain and nausea and vomiting at 60 minutes when compared to the placebo group in patients with cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome

Droperidol reduced ED LOS and additional emetic administration in patients with Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome.

Normal GI physiology and the pathogenesis of nausea and vomiting

Normal functioning of the GI tract involves the interaction between the gut and the central nervous system. The motor function of the gut is primarily regulated at three main levels [1].

Parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems

Enteric brain neurons

Smooth muscle cells

A major portion of normal GI motility involves the smooth muscles through the peristaltic reflex, which is important for the normal progression of a food bolus throughout the stomach and intestine.Abnormalities within any ofthreelevels can lead toabnormalities with the regulation of associated neurotransmitters, disrupting the peristaltic reflex and leading togastric stasisand decreasedgastric motility[2].

Nausea is primarily associated with the gastric rhythm disturbance from 3 cycles per minute, which is the normal gastric myoelectrical activity, to either increased activity (tachygastria) or decreased activity (bradygastria) [3].

Vomiting is a protective mechanism that allows animals and humans to purge ingested toxins. Induction of vomiting involves numerous afferent and efferent pathways. One is the area postrema on floor of the 4th ventricle which contains the “chemoreceptor trigger zone.” Another is the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the medulla, which acts as a central pattern generator for vomiting [4].

There are 3 basic phases of nausea and vomiting.

Nausea

Associated with tachycardia and increased salivation.

Retching

The contraction of the pylorus and relaxation of the fundus, allowing gastric contents to move to the gastric cardia.

Emesis

The forceful contraction of the abdominal musculature and relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, that allows the backward flow of contents from the stomach out the mouth [5].

Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis (GP) is a syndrome of delayed gastric emptying of solid material in the absence of mechanical obstruction. Although not directly linked to increased mortality, GP is associated with frequent ED visits, increased hospitalization and decreased quality of life [6].

A 2009 study that identified the incidence and prevalence of GP over 10 years in a Minnesota community found that the age-adjusted prevalence of the disease per 100,000 persons was 9.6 for men and 37.8 for women [7].

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of GP is poorly understood. There are many associated conditions, with diabetes mellitus (DM) being the most frequently recognized. Autonomic neuropathy has been thought to be the primary driver of diabetic GP, likely due to the assumption that it is related to diabetic neuropathy. Dysfunction of the Vagus nerve leads to decreased pyloric relaxation and passage of food is therefore prohibited. Hyperglycemia may also play a role, although acute episodes are typically reversible.

Other associated potential causes are Idiopathic, medication induced (narcotics, alpha-2 agonists, calcium channel blockers, dopamine agonists), post-surgical, or in the setting of neurologic disease [8].

Clinical presentation

Patients with GP can present with various, nonspecific complaints.

Most frequently, patients present with nausea (93%), vomiting (68-94%), abdominal pain (46-90%), early satiety (60-86%). Weight loss, dehydration and malnutrition are present in more severe cases [9].

Workup

The definitive diagnosis of GP is rarely made in the ED, since the gold standard for diagnosis is a gastric emptying scintigraphy of a solid phase meal [10].

ED workup involves recognizing red flags and complications of disease. The history/physical should address signs of alternative, potentially life-threatening diagnoses, including potential neurologic etiology, acute abdominal pathology, or progressive worsening or a change from typical symptom presentation.

Lab tests/imaging

CBC, BMP, LFTs, lipase, UA, bHCG

Consider:

ECG (if >50 or at risk for cardiac disease)

RUQ POCUS

CT abdomen/pelvis

If patient states that these symptoms are similar to prior exacerbations and there are no red flags, no imaging is necessary

Management

Management of GP is multilayered, involving lifestyle modification and diet control, with the primary focus of ED management treating acute attacks and complications of the disease [12].

Lifestyle modifications: nutrition and glycemic control

First line management in patients with GP should be the restoration of fluids and electrolytes in settings of dehydration, nutritional support and optimization of glycemic control in patients with diabetic GP [6].

Nutrition: Small meals that are low in fat and fiber. Liquid emptying tends to be preserved in GP, so blendarized solids may be considered. Oral intake is preferrable, but if unable to tolerate, tube feeding often pursued. Nasogastric tubes are beneficial in the short run as they allow for gastric decompression, but post-pyloric feeding is preferable due to erratic nutritional support from gastric delivery in these patients.

Glycemic control: Good glycemic control (<200) should be the goal as it has been shown that acute hyperglycemia inhibits gastric emptying. Pramlintide and GLP-1 should be avoided, as these medications may delay gastric emptying in diabetics [6].

Pharmacologic Agents

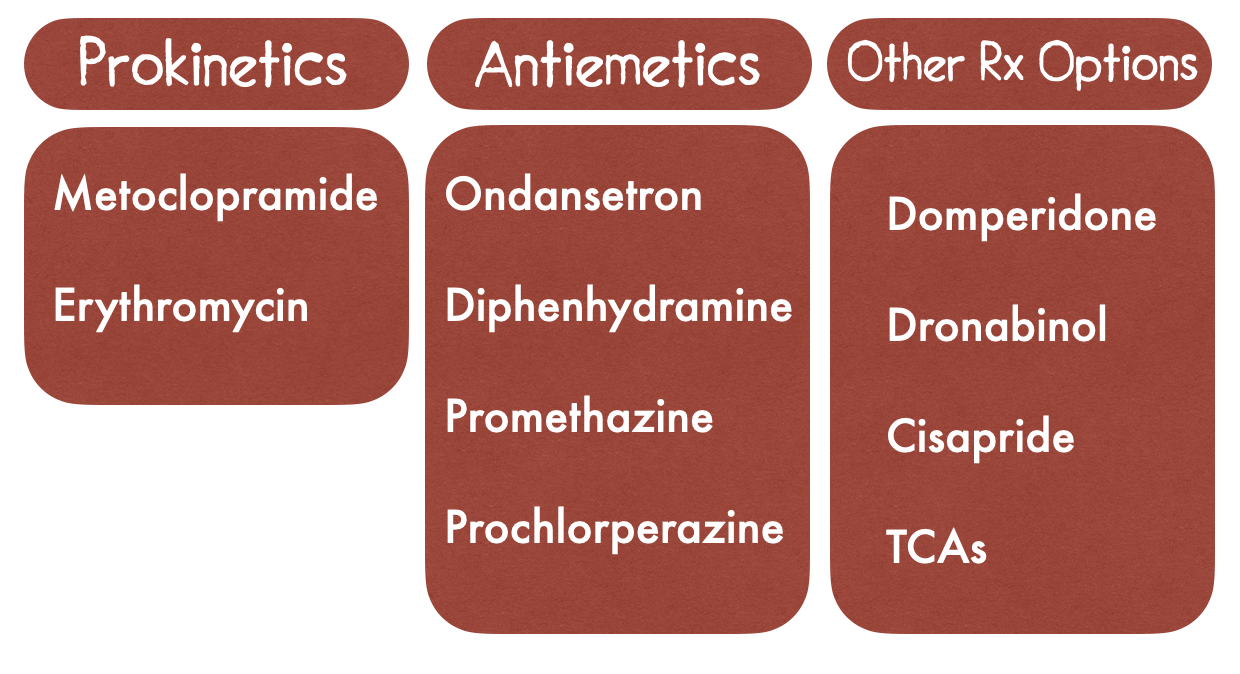

Many patients continue to experience symptoms after optimal lifestyle modifications. Management of GP involves usage of prokinetic agents to improve gastric motility as well as antiemetic usage for symptom control.

Prokinetics - The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology recommends prokinetics as the first line therapy for GP

Metoclopramide

Central and peripheral dopamine receptor antagonist, a 5-HT4 agonist and a weak 5-HT3 receptor antagonist

Improves gastric emptying by improving gastric antral contractions and decreasing postprandial fundus relaxation

Only FDA approved medication

5-10 mg TID

“Drug holidays” due to concern for extrapyramidal symptoms

Erythromycin

Motilin receptor agonist with prokinetic properties

Stimulates motilin receptors in GI tract to increase stomach-muscle contraction

IV 3.0 mg/kg TID for acute GP

Long term usage concerning for antibiotic resistance and C. Diff [6].

Antiemetics - For symptom control that is persistent following treatment with prokinetics. Does not improve gastric emptying. Use in gastroparesis is based on efficacy in controlling nonspecific nausea and vomiting [13].

Ondansetron (Zofran)

5-HT3 antagonist

4-8mg TID

Diphenhydramine (Benadryl)

First gen antihistamine

12.5- 25 mg q6-8h

Often used more reliably for nausea from motion sickness. Can also treat dystonic reactions for antipsychotic medications

Prochlorperazine (Compazine)

D2 dopamine antagonist

Promethazine (Phenergan)

First gen antihistamine

Other Treatment considerations

Domperidone

D2 dopamine antagonist, only available in patients who have failed metoclopramide or with severe side effects

Cisapride

5-HT4 agonist that stimulates antral and duodenal motility, only available in the US through investigational limited-access program due to drug-drug interactions resulting in cardiac arrhythmias

Dronabinol

Synthetic THC analog that is used as a second-line therapy in patients with refractory nausea and whom would benefit from appetite stimulation. Limited to short term use because of adverse effects like marijuana-like highs and binge eating

TCAs

In open label trials, low-dose nortriptyline, has been demonstrated to decrease symptoms of N/V in patients with diabetic gastroparesis. However, caution should be used as TCAs can potentially decrease the rate of gastric emptying [6,14].

Haloperidol undermining gastroparesis symptoms (HUGS) in the emergency department

Background - In 2017, a retrospective review was performed at a large urban emergency department in California. Patient with a diagnosis of diabetic GP who had received a 5mg IM injection of haloperidol between 2012 and 2015 were included in the study.

Methods - These patients were compared to themselves during their most recent hospital encounter in which haloperidol was not used. ED length of stay (LOS), additional antiemetics, hospital LOS and morphine equivalent dosage of analgesia for each visit were recorded and compared

Results - Haloperidol usage was associated with a statistically significant decrease in hospital admission (5/52 [10%] vs 14/52 [27%]) as well as analgesia administration. There was a decrease in the LOS in the ED (median 9.2h vs 25.4h) that was not statistically significant, although likely clinically significant [10].

Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome

Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome (CVS) was first described in 1882. The syndrome is defined by recurrent, stereotypical episodes of nausea and vomiting with periods of normal or baseline health in between. Social functioning, work, and education are majorly impacted in these patients, and they often will seek care in an emergency department many times prior to being diagnosed. A majority (93%) of these patients will not receive their diagnosis in the ED and close to 32% of patients will be completely disabled by the time they receive a diagnosis [15].

The prevalence of CVS is estimated to be 1.9-2.3% with an incidence of 3.2/100,000 population. The average age of diagnosis in the pediatric population is around 9.6 years, with symptom onset around 5 years [16]. In adults, the average age of symptom onset is 21 with an average age of diagnosis of 34. Adults can develop the disease without any episodes in childhood. There is a female predominance [17].

Pathophysiology

Like GP, CVS pathophysiology is not well understood. There are several proposed mechanisms including association with migraine headaches, sympathetic hyperresponsiveness, stress response caused by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, mutations in mitochondrial DNA (particularly in pediatrics) as well as potential cannabis usage [18].

Clinical presentation

In general, symptoms begin in the morning or on waking, with nausea and vomiting following within one hour. The nausea is not completely relieved by vomiting. Emesis rate peaks at 6x/hour. The episodes peak and then decline over the next 8 hours. These episodes are also associated with abdominal pain (60-80%), fever and/or diarrhea (33%), headache (43%), vertigo (26%), and photophobia (38%)

Differences by age

Pediatric:

Shorter episodes (1-2 days) that occur up to 12 times per year.

Triggers are more common and include infection as well as psychological or specific foods.

Adult:

Episodes generally last longer (3-6 days) but will have fewer cycles per year (4-5).

Triggers are less common for adults [20].

Official Criteria

Pediatric: North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN)

At least 5 episodes, or a minimum of 3 over 6 months

Episodes of N/V lasting 1h to 10 days with 1 week in between

Stereotypical pattern and symptoms

Return to baseline health between episodes

Symptoms not due to another disorder

Adult: Rome IV criteria:

Stereotypical episodes of vomiting with acute onset lasting less than 1 week

More than 3 discrete episodes in the past year with at least 2 episodes in past 6 months

Absence of vomiting between cycles, although more mild symptoms may be present [19].

Workup

Like GP, diagnosis of CVS is a diagnosis of exclusion. The emergency department workup should focus on evaluating for red flag symptoms (focal neurologic deficits, acute abdomen) and addressing complications (dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities)

Management

If there is no underlying etiology to address, treatment of CVS is based on three main components

Trigger avoidance/Prophylactic therapy

Abortive therapy

Supportive care [15].

Trigger avoidance & Prophylactic therapies

Patients will be aware of their own triggers. Although avoidance is not always practical, patients should be counseled on discharge, particularly if there is an association with cannabis usage.

Decision to use prophylactic therapy depends on the frequency and severity of the attacks. Generally warranted if:

Attacks occur monthly or last more than 1-2 days in children and adolescents.

If there are >4 episodes/year or last >2 days in adults.

If attacks are severe enough to require hospitalization or cause substantial absenteeism from school or work [21]

Prophylactic medications include:

Amitriptyline

First line

75-100mg per day

More effective in those with family history of migraines

Anticonvulsants (topiramate, zonisamide, levetiracetam)

Second line

Topiramate (100mg), zonisamide (400mg), levetiracetam (1000mg)

Mitochondrial supplementation

Adjunctive therapy

Very limited evidence

Coenzyme Q10 (200mg BID), Riboflavin (200mg BID) [15].

Abortive therapy

Abortive medications should be given to any patient with known CVS as soon as the nausea prodrome begins. Patients with delayed intervention (especially >24 hours after symptom onset) are more likely to require hospital admission [22].

Primary choices for abortive medications include sumatriptan and aprepitant

Sumatriptan: Moderately effective if given early in the prodromal phase and may have some effect if given within one hour of vomiting. has shown to provide anecdotal evidence of improvement in children with personal or family history of migraines and can be considered

6mg subcutaneous for adults (Hejazi et al)

Aprepitant: Oral neurokinin 1 antagonist antiemetic. Second line choice. Low quality evidence, suggestion reflects expert opinion

125mg orally on day 1 and 80 mg on day 2 and 3 [15].

Supportive care

Care in the emergency department typically focuses on supportive care during an acute episode of CVS. Acute phase treatment goals include preventing dehydration, improving N/V and abdominal pain.

Hydration

Dextrose, saline and potassium replacement

10% dextrose with 0.45-0.9% NS (Stanghellini et al)

Symptomatic control

5-HT3 antagonists such as ondansetron are often effective in controlling nausea, as are antihistamines promethazine and diphenhydramine.

Benzodiazepines can be considered for admitted patients requiring deep sedation or sleep induction

Lorazepam IV 1-2mg q3h (Hejazi et al)

IV opioids or Toradol may initially be needed to control the severe abdominal pain, but caution should be taken with opioids, as it can worsen gastric emptying [15].

What about Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome (CHS)?

This condition is associated with chronic, daily marijuana usage and characterized by daily vomiting episodes. Patients endorse diffuse abdominal pain that improves with hot showers/baths. Pathophysiology is unclear and duration of usage varies widely [23].

What’s this I hear about Capsaicin cream?

One randomized double-blind study done at a single urban academic trauma center compared N/V via previously validated visual analog scales (VAS). It was a small study with overall 30 patients included (17 treatment, 13 control). Endpoint was patients reported VAS at 30- and 60-minutes following administration of 5g of topical 0.1% capsaicin cream. In the treatment group, there was a statistically significant decrease in mean nausea VAS at 60 minutes compared with placebo and higher proportion of capsaicin group patients had complete resolution of nausea [23].

Although the study was limited by its small sample size, the trial helped to investigate alternative therapies for efficacious treatment of CHS.

But what about Droperidol? We haven’t talked about droperidol!

Droperidol is a highly popular medication used to treat nausea, vomiting, headaches and abdominal pain. There was one retrospective review performed at a single tertiary level metropolitan hospital that compared the length of stay and additional antiemetic administration between patients who received Droperidol and those who did not. In the droperidol treatment group, the median length of stay was significantly lower compared to the no droperidol treatment group (6.7h vs. 13.9 hours) and the frequency of Zofran and Compazine administration in the control group was double that of the droperidol group.

There have been several other studies done that evaluated the usage of droperidol in generalized nausea and vomiting as well as post-operative nausea and vomiting, but few that are specific for the more functional GI disorders [24].

Differentiating CVS and CHS?

The symptoms between these presentations are very similar and it is often hard to differentiate between these two syndromes. Patient must stop marijuana usage for at least one week. If symptoms resolve, cannabis hyperemesis is likely.

References

Camilleri M. Autonomic regulation of gastrointestinal motility. In: Clinical Autonomic Disorders: Evaluation and Management, Low PA (Ed), Little, Brown, Boston 1992. p.125.

Camilleri M. Gastrointestinal motility disorders in neurologic disease. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. https://www.jci.org/articles/view/143771. Published February 15, 2021. Accessed January 23, 2022.

Koch, K. L. (2014). Gastric Dysrhythmias: A potential objective measure of nausea. Experimental Brain Research, 232(8), 2553–2561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-014-4007-9

Carpenter, D. O. (1990). Neural mechanisms of emesis. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology, 68(2), 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1139/y90-036

The vomiting patient in the ED: Evaluation and management. Relias Media - Continuing Medical Education Publishing. (n.d.). Retrieved January 26, 2022, from https://www.reliasmedia.com/articles/13681-the-vomiting-patient-in-the-ed-evaluation-and-management

Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L. Clinical guideline: Management of gastroparesis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(1):1837. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.373

Jung, H. K., Choung, R. S., Locke, G. R., Schleck, C. D., Zinsmeister, A. R., Szarka, L. A., Mullan, B., & Talley, N. J. (2009). The incidence, prevalence, and outcomes of patients with gastroparesis in Olmsted County, Minnesota, from 1996 to 2006. Gastroenterology, 136(4), 1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.047

Parkman, H. P., Hasler, W. L., & Fisher, R. S. (2004). American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on the diagnosis and treatment of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology, 127(5), 1592–1622. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.055

Soykan, I., Sarosiek, I., Sivri, B., & McCallum, R. W. (1998). Demographic, clinical characteristics, psychological profiles, treatment and follow-up of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology, 114. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5085(98)83424-0

Ramirez R, Stalcup P, Croft B, Darracq MA. Haloperidol undermining gastroparesis symptoms (hugs) in the emergency department. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;35(8):1118-1120. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.03.015

Abell TL, Bernstein VK, Cutts T, et al. Treatment of gastroparesis: A multidisciplinary clinical review. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00760.x. Published February 14, 2006. Accessed January 23, 2022.

Zheng T. Management of gastroparesis. Gastroenterology Hepatology. https://www.gastroenterologyandhepatology.net/archives/november-2021/management-of-gastroparesis/. Accessed January 23, 2022.

Manouchehr Saljoughian PD. A new approach to managing gastroparesis. U.S. Pharmacist – The Leading Journal in Pharmacy. https://www.uspharmacist.com/article/new-approach-to-managing-gastroparesis. Published February 15, 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022.

Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, Abell TL, Gerson L. Clinical guideline: Management of gastroparesis. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;108(1):18-37. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.373

Venkatesan, T., Levinthal, D. J., Tarbell, S. E., Jaradeh, S. S., Hasler, W. L., Issenman, R. M., Adams, K. A., Sarosiek, I., Stave, C. D., Sharaf, R. N., Sultan, S., & Li, B. U. (2019). Guidelines on management of cyclic vomiting syndrome in adults by the American neurogastroenterology and motility society and the Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Association. Neurogastroenterology & Motility, 31(S2). https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13604

Fitzpatrick, E., Bourke, B., Drumm, B., & Rowland, M. (2008). The incidence of cyclic vomiting syndrome in children: Population-based study. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 103(4), 991–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01668.x

Kumar, N., Bashar, Q., Reddy, N., Sengupta, J., Ananthakrishnan, A., Schroeder, A., Hogan, W. J., & Venkatesan, T. (2012). Cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS): Is there a difference based on onset of symptoms - pediatric versus adult? BMC Gastroenterology, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230x-12-52

Li, B. U. K., & Misiewicz, L. (2003). Cyclic vomiting syndrome: A brain–gut disorder. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America, 32(3), 997–1019. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0889-8553(03)00045-1

Williams, S. E., & Bursch, B. (2017). Diagnostic and treatment approaches associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders in children and adolescents. Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315670355-22

Fleisher DR, Gornowicz B, Adams K, Burch R, Feldman EJ. Cyclic vomiting syndrome in 41 adults: The illness, the patients, and problems of Management. BMC Medicine. 2005;3(1). doi:10.1186/1741-7015-3-20

Gui, S., Patel, N., Issenman, R., & Kam, A. J. (2019). Acute management of pediatric cyclic vomiting syndrome: A systematic review. The Journal of Pediatrics, 214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.06.057

Abdulkader ZM, Bali N, Vaz K, et al. Predictors of Hospital Admission for Pediatric Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome. J Pediatr 2021; 232:154

Ramzy Wby M. Topical capsaicin & cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. REBEL EM - Emergency Medicine Blog. https://rebelem.com/topical-capsaicin-cannabinoid-hyperemesis-syndrome/. Published September 12, 2020. Accessed January 23, 2022.

Lee, C., Greene, S. L., & Wong, A. (2019). The utility of droperidol in the treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Clinical Toxicology, 57(9), 773–777. https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2018.1564324

Authorship

Written by: Olivia Gobble, MD, PGY-1, University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine

Peer Review, Editing, and Posting: Jeffery Hill, MD MEd, Associate Professor, University of Cincinnati Department of Emergency Medicine