Feeling "Dizzy"

/This month we have the pleasure of discussing the chief complaint of “dizziness” with Dr. William Knight. In the attached podcast much of our discussion regarding this symptom focuses on stroke as a cause of this complaint. Even so, it is important to remember that not all patients who present to the emergency department with dizziness are experiencing a stroke. Quite the opposite; the majority of patients seeking care for feeling “dizzy” or “lightheaded” or “imbalanced” will have a cause other than restriction of blood flow to, or bleeding into, the posterior fossa. One national survey found that of patients presenting to the ED for “dizziness”, half had a medical (i.e. non-vestibular and non-neurological) cause for their symptoms.1 The differential diagnosis for dizziness is wide in etiology as well as severity. It is important to consider that this chief complaint could represent anything from carbon monoxide poisoning to the combination of chewing tobacco and carnival rides.

Even so, posterior circulation stroke (PCS) warrants discussion considering the potential difficulty in diagnosis as well as the serious consequences if missed. When compared head to head with that of anterior circulation stroke (ACS), PCS has been found to have delay in consultation with neurologic services and administration of tPA.2In this cross sectional study, all patients that received tPA for acute ischemic stroke were divided into either ACS or PCS groups following diagnostic testing and characteristics regarding patient demographics, risk factors, “door to needle time” (i.e. how long until tPA was administered) and time until stroke team/neurology specialty evaluation. Though pre-hospital transport time and other variables remained consistent across both groups, PCS patients had delay in treatment and specialty evaluation by approximately 15 minutes. Fortunately, no significant clinical outcome difference was found, however, the pattern for delay in action raises concern. A statistically significant difference in NIH stroke scale was found between the two groups, with PCS having a lower average rating of 6 (compared to 13 for ACS). It is possible to infer that the combination of less obvious physical examination findings in combination with potentially less classic stroke presentation may lead to delay in consideration of stroke on the differential.

Dr. Knight provides insight into the best way to avoid the trap of dismissing truly sick dizzy patient; that of high clinical suspicion. It can be all too easy to quickly run through a history and physical exam while the patient lays on a gurney, but these are situations where the inconvenience of some more thorough medical history and patient ambulation is certainly worth your time. Keep in mind traditional risk factors for stroke including atherosclerotic and thromboembolic precipitators/associates such as diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, positive smoking history, advanced age, and atrial fibrillation.3Other things to consider in history include the chronology of symptoms and surrounding events. An example Dr. Knight provides is that of acute head and/or neck trauma with temporal and abrupt association of dizziness symptoms that should raise your concern for vertebral artery dissection. Physical examination can be key in detecting subtle findings that can greatly change a patient’s diagnostic trajectory. Specifically, regarding basilar artery occlusion (BAO), a feared subset of PSC more famously known for its potential of resulting in “locked in syndrome”, oculomotor palsies, truncal and limb ataxia, oropharyngeal dysfunction and limb weakness are found to be the most common signs that can be found on exam.4 It is also prudent to be wary of atypical nystagmus (such as vertical or alternating horizontal) as a potential signal for posterior circulation injury.

These warnings paint a grisly picture for the dizzy patient, but fortunately there are some ways to find re-assurance in the evaluation of this group. One study5 set out to evaluate for any benign appearing patients with a chief complaint of dizziness who were actually suffering from an intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). As a population based study, a database was reviewed to find all patients with dizziness who were found to have an NIH stroke scale score of <2 who were found to have an ICH on head CT. Of 591 ICH cases reviewed, only 13 (2.2%) met these two criteria. Further examination found that none of these 13 had a normal neurologic examination and that only one case had isolated dizziness as a symptom. Though this study is limited for our purposes in the sense that this is not regarding ischemic stroke patients, it does further emphasize the importance to heavily consider CNS pathology in the patient who is dizzy plus (i.e. dizzy plus additional physical exam finding/symptom/traumatic history, etc).

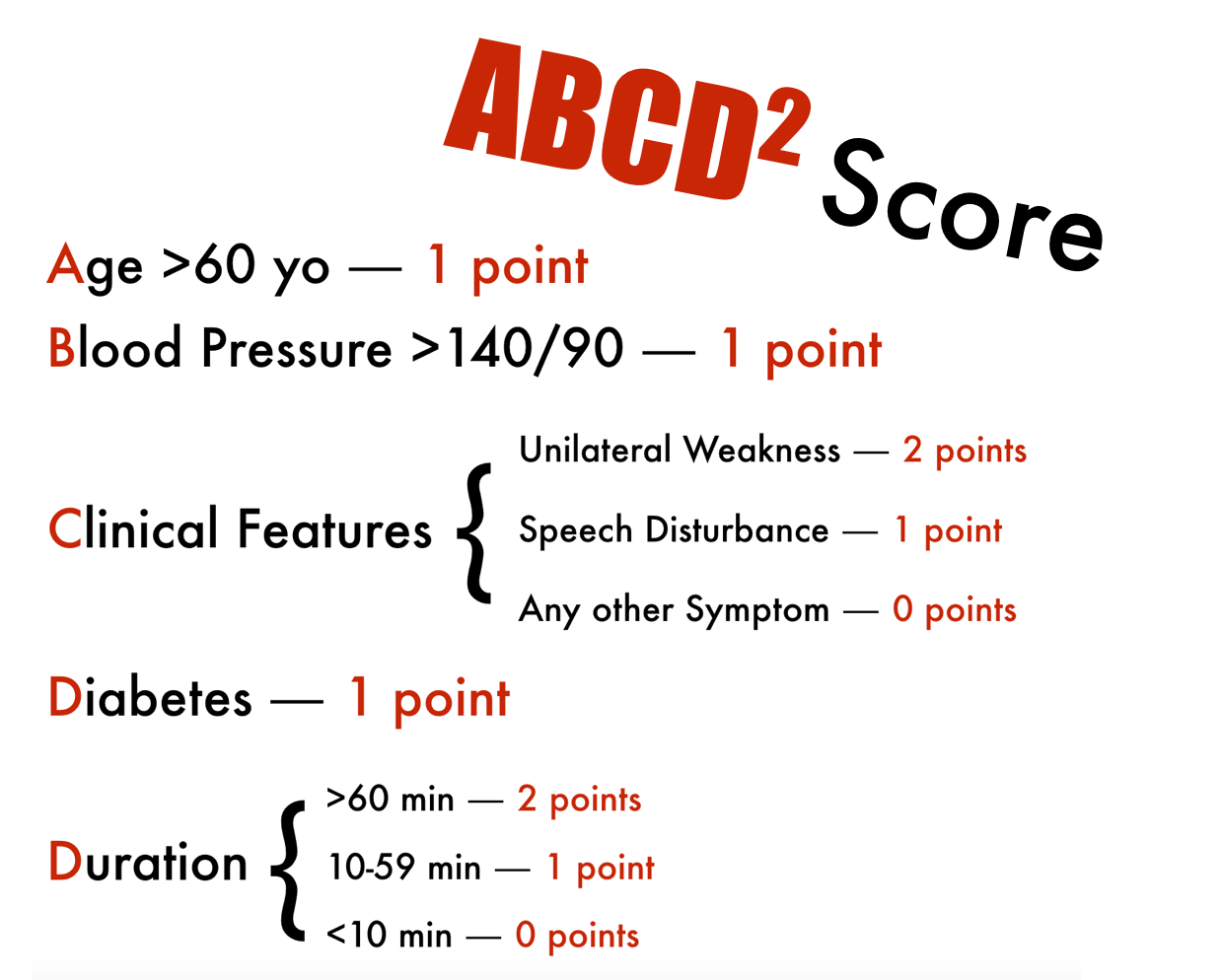

Other efforts have been made to help risk stratify patients for ischemic PSC. In a retrospective observational study6 the ABCD2 score was applied to patients with a chief complaint equitable to dizziness to evaluate for its effectiveness as a screening tool for ischemic stroke/TIA as cause of that symptom. In the following interpretation, it is important to note that as there were not specific time values available for duration of symptoms on most patients that all patients were assigned a 60+ minutes score in their evaluation for the study.

On review, of patients with an ABCD2 score of less than or equal to 3, only 5 of 512 patients had a cerebrovascular diagnosis as cause of their symptoms. Of those 5, all had at least 2 vascular risk factors. Among their findings they also report a positive likelihood ratio ranging from 1.3 for a score of 3 to the range of 7-8 for a score in the range of 6-7. Although this study does have its limitations and certainly doesn’t provide the evidence necessary to effectively rule out stroke through its application, it can be a useful tool for reinforcement of your assessment of a patient’s risk for stroke when presenting with dizziness.

As for imaging, keep in mind Dr. Knight’s advice; unless you’re looking for intracranial bleeding, non-contrast CT scan of the head won’t offer you much in regards to PSC. Look here7 for some interesting reading regarding hyper dense posterior circulation arteries on CTA and what their presence may imply. We won’t go into it or MRI further, otherwise this post will go on...

References

- Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA Jr, et al. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc 2008;83:765–75.

- Sarraj, Amrou, et al. "Posterior circulation stroke is associated with prolonged door‐to‐needle time." International Journal of Stroke (2013).

- Datar, Sudhir, and Alejandro A. Rabinstein. "Cerebellar Infarction." Neurologic clinics 32.4 (2014): 979-991.

- Demel, Stacie L., and Joseph P. Broderick. "Basilar Occlusion Syndromes An Update." The Neurohospitalist 5.3 (2015): 142-150.

- Kerber, Kevin A., et al. "Does intracerebral haemorrhage mimic benign dizziness presentations? A population based study." Emergency Medicine Journal 29.1 (2012): 43-46.

- Navi, Babak B., et al. "Application of the ABCD2 score to identify cerebrovascular causes of dizziness in the emergency department." Stroke 43.6 (2012): 1484-1489.

- Goldmakher, Gregory V., et al. "Hyperdense basilar artery sign on unenhanced CT predicts thrombus and outcome in acute posterior circulation stroke." Stroke 40.1 (2009): 134-139.