Grand Rounds Recap 11.29.17

/Morbidity and Mortality Conference with Dr. Lagasse

Case One

Malignancy & Sepsis

- Sepsis is the leading cause of mortality in patients who are undergoing chemotherapy for solid organ malignancies.

- Malignancy with sepsis criteria (e.g., SIRS, qSOFA) is an oncologic emergency, and delayed initiation of antibiotics is associated with poor clinical outcomes.

- Patients may not have a true fever but can still be septic; maintain a high index of suspicion for sepsis in patients undergoing active chemotherapy

- We should be starting antibiotics on these patients even if we do not have a clear source.

- Most guidelines, including our own ED protocols, recommend giving antibiotics as soon as possible from arrival to the ED (goal less than <2 hours).

- Use order sets -- evidence shows a decrease in time to antibiotic administration when order sets are utilized, as it gets everyone on the same page (nursing staff, pharmacy and the physicians). Our institution has an EMR-based order set for neutropenic fever.

Case Two

Intraocular Foreign Bodies (IOFB)

- Most frequently seen in young males with a history of ocular trauma; risk factors include use of power tools, metal-on-metal impacts and projectile weapons.

- These are also seen in up to 40% of open globe injuries.

- CT scan is considered the gold standard for diagnosis of IOFB; ocular ultrasound (discussed in this issue of Annals of B Pod) can be used but is contraindicated if you are concerned about an open globe injury.

- MRI is contraindicated if you are concerned for a metallic foreign body, but is the best imaging modality for organic foreign bodies, and should be considered if a CT is negative despite high clinical suspicion.

- IOFBs need to be removed within 24-48 hours of presentation, and these patients should be admitted to the hospital for surgical planning.

- IV antibiotics are required, although there is poor vitreal penetration of antibiotics in general, and often intravitreal injections need to be performed.

- Endophthalmitis is the dreaded complication of a retained IOFB (see our Annals of B Pod issue that discusses endophthalmitis here); post-traumatic endophthalmitis should be considered a retained IOFB until proven otherwise.

Case Three

ED Management of Pleural Effusions & Empyemas

- Empyema occurs as a complication of pneumonia and pleural effusions; the tenets of management include drainage, lung reexpansion and giving appropriate antibiotics.

- Indications for drainage include purulence, an effusion >50% of the hemithorax or imaging concerning for a loculated effusion, as well as for worsening respiratory status or symptomatic control.

- There is no consensus regarding the ideal drain size; per the American Thoracic Society, small bore tubes (20 F or less) are accepted as first-line therapy, as it is tolerated better by the patient with equal clinical efficacy compared to larger tubes.

- However, there is some concern that small-bore catheters (such as a pneumocath) are not adequate in draining pleural effusions, so the smaller chest tubes are recommended over smaller catheters.

- Ultrasound is more sensitive at identifying a pleural effusion than a lateral decubitus CXR, so consider utilizing this in your workup.

- Empyemas require a second or third generation cephalosporin AND metronidazole or an aminopenicillin.

Case Four

Cardiac Dysfunction & Sepsis

- There is a growing body of evidence to support a complex alteration in cardiac function in sepsis, although there is no clear guidelines as to what defines septic cardiomyopathy.

- Cardiac dysfunction in sepsis is associated with increased mortality, so this is important for the Emergency Physician to understand and recognize early on in the resuscitation.

- Shock states can co-exist; the above patient had both distributive and cardiogenic shock.

- Some patients respond well to fluid resuscitation in sepsis, but some patients have persistent low stroke volumes despite volume expansion; these are the patients who will have cardiac dysfunction in sepsis and have an ultimate greater mortality.

Endocarditis & Sepsis

- Patients with endocarditis are especially prone to cardiac dysfunction in sepsis due to the pathophysiology of their underlying disease.

- Endocarditis patients need standard sepsis care to include antibiotics, IV fluids and vasopressors; however, inotropes should be considered early in these patients, and dobutamine is recommended by the European Society of Cardiology as a second line agent after levophed in endocarditis

Case Five

Transport of Critically Ill Patients

- Intrahospital transport of critically ill patients must be performed when benefit outweighs the risk.

- Most of the studies on this concept have been based around patients being transported from an ICU setting to somewhere within the hospital (such as radiology), but they can likely be extrapolated to our role in the ED.

- For ICU patients, the benefit of transport is usually some type of change in their management; for example, transporting a patient to radiology for a CT scan could identify an etiology for their sepsis or hypotension.

- In the ED, we are not the patient's ultimate destination, but we can provide a high level of care as well for an unstable, critically ill patient, so we may be a safer place instead of sending a patient to the ICU.

- Sometimes the destination matters: we will transport an unstable patient from the ED to the OR for definitive management, or to the cath lab for cardiac intervention.

- Risk factors for adverse events during transport include: sedation before transport, a PEEP > 6, a high number of infusion pumps and recent treatment modification prior to transport.

- The Society of Critical Care Medicine does have guidelines about the transport of these patients, which includes making sure you have the appropriate personnel (usually a nurse plus one other staff member), appropriate equipment (including monitoring, drugs and a BVM).

- Johns Hopkins has an intrahospital transport team, and has seen some improvement in their adverse events in this arena, although they do not transport patients out of the ED.

- Communication is key: make sure the receiving team knows the severity of the patient's illness so there are no surprises, and talk to your team -- giving nurses discrete plans for deterioration in transport can be helpful.

- For patients with severe metabolic acidosis with high minute volume requirements, be cognizant of how a patient will be transported from a respiratory standpoint; bagging is inferior to a transport ventilator, as a vent can maintain a constant minute volume and avoid worsening acidosis.

- Ultimately, we must use our best clinical judgement about what destination is the best for the patient, and communicate the potential for deterioration with the clinical team.

Case Six

DDAVP & Intracranial Hemorrhage (ICH)

- Antiplatelet agents include agents that are reversible and non-reversible; the latter agents can affect platelet function for up to 20 days.

- It remains controversial in the literature whether antiplatelet agents influence ultimate neurologic outcome in patients with ICH.

- DDAVP (desmopressin) has been shown to reverse lab abnormalities caused by COX-1 inhibitors and ADP receptor inhibitors.

- There is a paucity of literature on the topic, but several small studies focusing on patients with ICHs on antiplatelet agents showed improvement in platelet function tests at the one hour mark after receiving DDAVP, but the effect may be transient.

- DDAVP in general has a low risk of serious side effects, is relatively inexpensive and is weight-based.

- You may consider a single dose of DDAVP (0.4 mcg/kg) in ICH patients exposed to antiplatelet agents; our institution does not currently have a standardized policy regarding this, so discuss with your consultants before administering this drug.

R1 Clinical Diagnostics: Heart Blocks with Dr. Iparraguirre

Please see Dr. Iparraguirre's primer on heart blocks here.

Case One

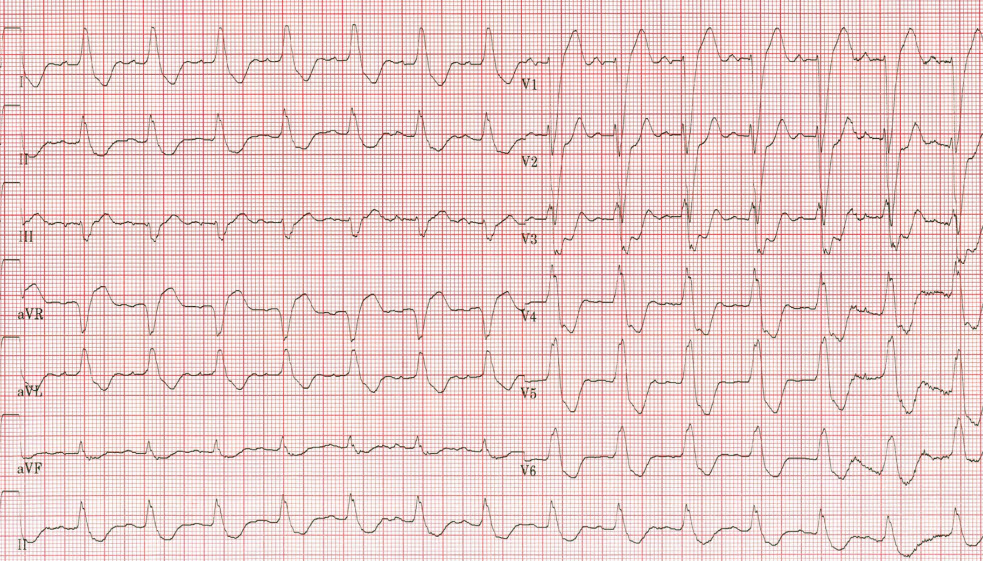

The patient is a male in his 60s who presents to the ED with lightheadedness. He reports that he has had some nausea and vomiting with limited PO intake over the last few days. On exam he is found to be bradycardic in the 50s with an irregular rhythm. His EKG is notable for a bradycardic rate with intermittently non-conducted p waves without any PR prolongation, concerning for Mobitz II.

Given his recent gastroenteritis, there was concern that this was due to electrolyte abnormalities. He was admitted to the hospital for monitoring and pacemaker evaluation. This is different than the management of Mobitz I, who have a low risk of progression to complete heart block and can be monitored or discharged home depending on the clinical picture.

Case Two

The patient is a male in his 60s who presents with dyspnea and chest pain for a week. He has a history of CHF, HTN and DM. He is found to have significant peripheral edema on exam with orthopnea. A CXR is notable for pulmonary edema, and he does have JVD on exam. He is bradycardic in the 50s but maintaining a normal blood pressure. An EKG is notable for complete discordance of the p waves with the QRS segment with a bradycardic rhythm.

He is found to be in complete heart block and is admitted to the hospital for a pacemaker. If he were to deteriorate from a hemodynamic standpoint, it is rare that atropine will help, although most algorithms still include atropine administration for symptomatic bradycardia. These patients typically require transcutaneous or transvenous pacing until definitive management with a pacemaker.

Case Three

The patient is an elderly female with a history of CAD, HTN and GERD who presents with acute onset of abdominal pain. On exam, she is uncomfortable appearing and diaphoretic. Her EKG is notable for a LBBB with inappropriate ST depression (excessive concordance) in the precordial leads by Sgarbossa Criteria.

The cath lab is activated and the patient goes for PCI.

R2 Cpc with Dr. nagle and Dr. Lafollette

The patient is a male in his 70s who presents with AMS. He has a history of previous ACA stroke, a seizure disorder on Keppra, dementia and urinary retention. He presents from his nursing home for generalized AMS; per the nursing home and EMS, the patient is usually ambulatory and interactive and was last seen normal sometime yesterday evening. There is no report from the nursing home of any recent illness, fever or trauma.

The patient is found to have relatively normal vitals but remains globally altered. He responds to yes/no commands but cannot otherwise verbally communicate. His lungs are clear and his abdomen is benign. He has an otherwise non-localizing neurologic exam. An EKG is notable for sinus tach. Labs are notable for a UA with >100 WBCs and a otherwise laboratory evaluation with a normal lactate.

The differential for this patient's AMS includes:

- Seizures

- Acute change in mental status does support this

- Non-convulsive status should be considered in any patient with a seizure disorder who is acutely altered

- UTI could lower seizure threshold

- Age and dementia history also contribute to increased risk profile

- Acute Stroke

- Non focal exam but still a possibility given his history

- Consider imaging the posterior vasculature (CTA head/neck) in patients with global alteration and any brainstem findings (nystagmus, ocular movement abnormalities, etc)

- Metabolic or infectious encephalopathy

- Has evidence of UTI on laboratory exam; could his AMS be due to a recrudescence of his previous stroke given his UTI? Unlikely as alteration in UTI is confusion > gait abnormalities > focal weakness mimicking prior deficit

- PNA unlikely given normal CXR

- Encephalitis and meningitis unlikely given lack of supporting evidence

- In general, acute change in mental status instead of gradual decline does not support primarily infectious process

- Complex Migraine

- No history of such in this patient

- Toxicologic

- Unlikely to be a toxicity of any of his listed medications

- Remainder of tox labs and urine drug screen were negative

- Presentation does not fit clear toxidrome

Ultimately, neurology was consulted and the patient underwent a continuous EEG in the Emergency Department and was found to be in non-convulsive status epilepticus (NCSE) with seizure activity in the left frontotemporal lobe.

NSCE

- Defined as status epilepticus without prominent motor symptoms for 30 minutes.

- Can also be brief intermittent seizure activity without convulsions without full recovery of consciousness between attacks.

- NSCE represents up to 25% of all status cases; up to 24% of all ICU patients with generalized altered mental status may be in non-convulsive status.

- Can be diagnosed in the ED; patients in NSCE will usually have epileptiform activity within 30 minutes of being hooked onto EEG.

- Things to look for on physical exam include: changes in behavior; subtle motor findings such as facial twitching; ocular involvement; automatisms; or changes in speech.

- Populations at risk include: elderly patients with fluctuating or profound AMS; critically ill patients who are obtunded or in a coma; patients who are post-generalized convulsive status but not returning to baseline; or a previous history of seizure, stroke or neurotrauma.

- Treatment should be done in conjunction with the admitting team but often benzodiazepines can be diagnostic and therapeutic.

This patient required multiple AEDs to break his NCSE but ultimately did well.

mastering minor care: Abscess management with Dr. paulsen

- There are over 4 million annual visits to the ED for abscesses; the incidence is increasing, thought to be secondary to the rise of resistant bacteria as well as IV drug use.

- There is fair interrater reliability at diagnosing an abscess, and moderate reliability regarding whether an abscess would need to be drained.

- Point of care ultrasound increases our ability to manage skin and soft tissue infections appropriately; sensitivity of bedside ultrasound for diagnosing the presence of an abscess is as high as 97% with a specificity of 83% and a LR of 5.5.

- Analgesia for abscesses include lidocaine field blocks as well as oral medications such as NSAIDs or even opiates depending on the severity of the abscess.

- The size of the incision matters: needle aspiration has a significantly higher failure rate at seven days (74%) compared to a conventional I&D (20%)

- Another drainage technique, especially in more aesthetic areas, is to perform a loop drainage. In this procedure, a penrose drain or other small rubber catheter is placed through two smaller incisions through the abscess. Studies have shown that failure rates are commensurate with traditional I&D but with better pain control and cosmetic outcomes.

Is irrigation necessary?

- Probably not. In one study, irrigation was not associated with decreased need for repeat intervention. This is something that can be done, but is not necessary in all cases.

Is packing necessary?

- Probably not. In one study, there was no change in treatment failure in the patients who received packing, but those patients had more pain, so guidelines recommend simply to consider packing in some patients. You can also consider loop drainage in patients instead.

Is primary closure ever an option for abscesses?

- There is not a lot of literature on this, but in select healthy patients with abscesses on the trunk or extremities, a single mattress suture was found to decrease the time for wounds to heal. There is no significant evidence as to whether this increases failure rates, however.

Who needs antibiotics?

- Practice patterns are wildly variable. For all comers with uncomplicated abscesses, failures at 30 days are similar in patients who received antibiotics versus placebo, suggesting antibiotics are unnecessary for many patients with abscesses. However, guidelines suggest antibiotics for anyone with evidence of a purulent infection with systemic signs of infection, those who are immunocompromised, and those who have failed I&D. In our institution, clindamycin has poor sensitivities (<70%); consider bactrim or doxy instead.

- Most patients can be safely discharged with close follow-up for a wound check. In rare cases, some patients may need to be admitted for surgical management or IV antibiotics.

r4 clinical soapbox: patient turnover with Dr. goel

- Patient handoffs are defined as "a transfer and acceptance of patient care achieved through communication" but are fraught with the potential for patient harm.

- Hand off in the ED includes change of shift, admission to an inpatient service and transfer from another hospital.

- There are specific ACGME requirements for handoffs and transfer of care.

- Medical errors attributed to problems with handoff account for up to $1.7 billion dollars a year in health care expenditures.

- Studies focusing on handoffs in the ED have shown that a majority of clinicians feel distracted during handoff by clinical duties, and there are varied opinion on who is responsible for patient care once handoff or admission has occurred.

- Problems inherent to the handoff process include lack of standardization, poor communication, and time constraints.

- While there are many facets to errors in handoffs, a standardized handoff process has been shown to reduce overall medical errors.

- These standardized handoffs include common processes such as IPASS or SBAR.

- Human error can be mitigated by recognizing the inherent dangers of patient handoff; these can be mitigated by consciously creating a clear signout plan for your colleague, reassessing patients when you assume care, and consider the integration of EMR or a standardized written or verbal handoff process.

R3 Taming the SRU: lytics in pulmonary embolus with Dr. McKee

The patient is a male in his 50s with a recent lower extremity injury as well as a history of HTN and obesity. He first presented to our sister community hospital with acute onset shortness of breath. He was found to have laboratory evidence of right heart strain, but was unable to get a CTPA. He was admitted to the outside hospital ICU on a heparin drip due to high clinical concern for PE, but got progressively hypoxic and hypotensive there. A bedside cardiac ultrasound showed a dilated RV with flattening of the septum. The decision was made to transfer the patient to our hospital for consideration for catheter-directed thrombolytics due to a history of a remote GI bleed.

He was originally slated to go to the cath lab, but was redirected to the Emergency Department due to instability. On arrival, he was hypoxic on BiPAP, tachypneic and hypotensive. The decision was made to intubate the patient due to his worsening respiratory failure. However, after intubation he developed profound hemodynamic instability and sustained a cardiac arrest.

Massive PE and Shock

- In patients with massive PE, hypoxia is not the killer -- hemodynamic collapse is.

- Increased RV strain ultimately leads to decreased LV preload, causing progressive hypotension, obstructive shock and cardiac arrest. Additionally, RV coronary perfusion and O2 deliver is ultimately compromised, contributing to a component of cardiogenic shock as well.

- IV fluids should be given judiciously with respect to where you think the patient is on the Starling curve.

- Instead, early and aggressive vasopressor and inotrope support should be considered.

- Consider the use of pulmonary vasodilators to offload the RV.

- If the patient codes, what is the role of systemic thrombolysis? The evidence is poor and there is no consensus on timing, dosing or administration methods.

The patient ultimately received tPA and had sustained ROSC. After a prolonged hospital stay he was discharged home with some residual disabilities and an ECOG score of 3.