Traumatic Shoulder Injuries

/The shoulder is a complex joint consisting of bony, tendinous, cartilaginous, muscular, and neurovascular structures. Trauma to this complex is common, and deserves attention by the emergency clinician, as injuries to the various structures comprising the shoulder carry significant morbidity and often occur in young, healthy individuals. Traumatic shoulder injuries are very common, and account for 4.35% of all injury-related emergency department visits in the United States (1). In this post, we will discuss common traumatic shoulder injuries seen in the emergency department with attention paid to the evaluation, management, disposition, and special considerations for patients presenting with acute traumatic shoulder injuries.

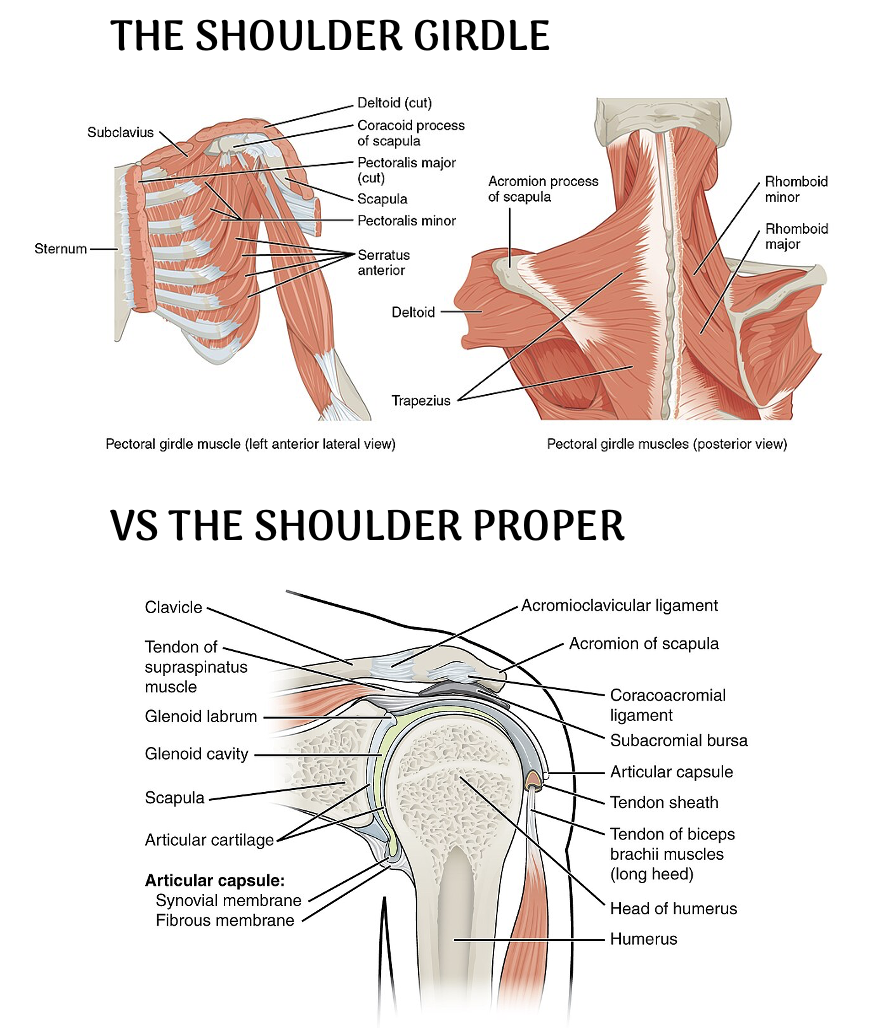

Overview and Review of Anatomy

A lot of people use the word “shoulder” to mean anything from the collarbone to the upper arm, but anatomically it’s really two related systems: the shoulder girdle, which moves and positions the scapula, and the shoulder joint, which actually moves the arm. Understanding which structure you’re referring to matters—especially when you’re describing injuries to consultants or translating findings into language patients can understand.

The shoulder girdle—made up of the clavicle and scapula—anchors the upper extremity to the torso and controls the big, positional movements of the scapula. Its three functional joints (sternoclavicular, acromioclavicular, and the scapulothoracic articulation) allow elevation, depression, protraction, retraction, and rotation of the shoulder blade. These motions set the “starting position” for everything the arm does. In addition, crossing within the shoulder girdle are several large and important nerves and vessels, including the brachial plexus, the axillary artery, and the axillary vein. It is important to be aware that all of these structures can be injured when the shoulder is injured, making a complete physical exam a high priority when an injury in this area is discovered.

The shoulder joint, or glenohumeral joint, or the “shoulder proper”, is the ball‑and‑socket articulation between the humeral head and the glenoid. This is the joint responsible for the arm’s sweeping range of motion: flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation, and circumduction. The key relationship is simple but clinically important: the girdle moves the base, and the joint moves the arm.

Physical Examination and Imaging

General evaluation of patients presenting to the emergency department with acute traumatic shoulder injuries should follow a standard trauma evaluation. After completing an ATLS trauma assessment from head to toe to assess for life-threatening injuries, dedicated examination of the shoulder structures can be completed. Special attention should be paid to a thorough neurovascular examination as well as provocative maneuvers as indicated.

Some sort of imaging is often obtained in the initial evaluation of acute trauma to the shoulder. While simple radiography is typically first-line and should be completed for most patients presenting with acute shoulder trauma, there is some role for ultrasound (often used in identification of shoulder dislocations for example) , CT (evaluation of complex fracture), and MRI depending on history. For example, most ligamentous, tendinous, and labral injuries will ultimately require MRI imaging, but this is rarely indicated in the acute emergency department setting. If there is concern for vascular injury (i.e. clavicular fractures with distal pulse asymmetry or diminished brachio-brachial index), CT angiography may be indicated.

A great video example of the complete shoulder exam can be found in this companion post, also on Taming the SRU.

BONY INJURIES: Fractures of the Shoulder Girdle

Account for 20-35% of acute shoulder injuries seen in the Emergency Department (1,2).

1) Proximal Humerus Fractures

Risk Factors: older age, osteoporosis, female sex

Mechanism: usually direct impact (i.e. fall from standing)

Fracture Patterns:

Anatomic Neck - High risk for avascular necrosis of the humeral head

Surgical Neck

Greater tuberosity

Lesser tuberosity

Humeral head split fracture – Occurs when the humeral head splits as it is forced medially against the glenoid

ED Management: Most proximal humerus fractures are managed nonoperatively and can be discharged from the emergency department in a sling with close orthopedic follow-up. Indications for surgery are based on two primary classification systems (AO/OTA and Neer Classification) that classify fractures based on fracture location, displacement, and comminution. Common surgical indications include displaced surgical neck fractures, greater tuberosity fractures with >5mm of displacement, and comminuted humeral head fractures (including head split and those with intra-articular extension) (3).

Any open fracture or fracture that involves a non-reducible shoulder dislocation requires emergent orthopedics consultation.

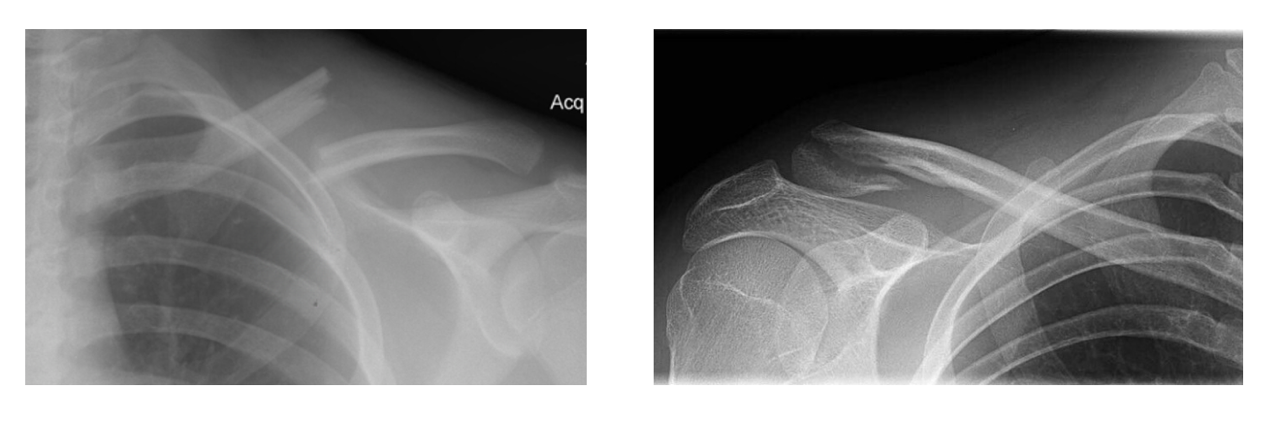

2) Clavicle Fractures

Risk Factors: Old age, young age

Mechanism: Direct impact (i.e. fall on lateral shoulder), birth trauma (i.e. newborn)

Fracture Patterns. The Allman Classification characterizes clavicle fractures by their anatomic location (4):

Group 1- Middle third

Most common, accounts for 79-81% of all clavicle fractures

Generally managed nonoperatively

Usually result in apex-superior angulation, which can cause skin tenting and open fracture

Comminution can cause Z-type pattern, which carries high risk for nonunion

Group 2 - Lateral Third

Accounts for 19% of all clavicle fractures

Generally managed nonoperatively

Group 3 - Medical Third

Rare, accounts for <2% of all clavicle fractures

Usually with posterior displacement of the medial fragment

High risk for neurovascular injury, as the subclavian vessels, brachial plexus, and even trachea underly the medial clavicle

Generally require operative management

ED Management: Most isolated clavicle fractures are managed nonoperatively and can be discharged from the emergency department in a sling. Emergent orthopedics consultation is indicated for all open fractures, posteriorly displaced medial third fractures, and with any evidence of neurovascular compromise. Fractures with skin tenting resulting in blanching are at high risk of becoming open and should also be evaluated emergently. Z-type fractures with >2cm of overlap and severely comminuted fractures will often be repaired surgically; however, they can be safely discharged from the ED with close orthopedics follow-up (5).

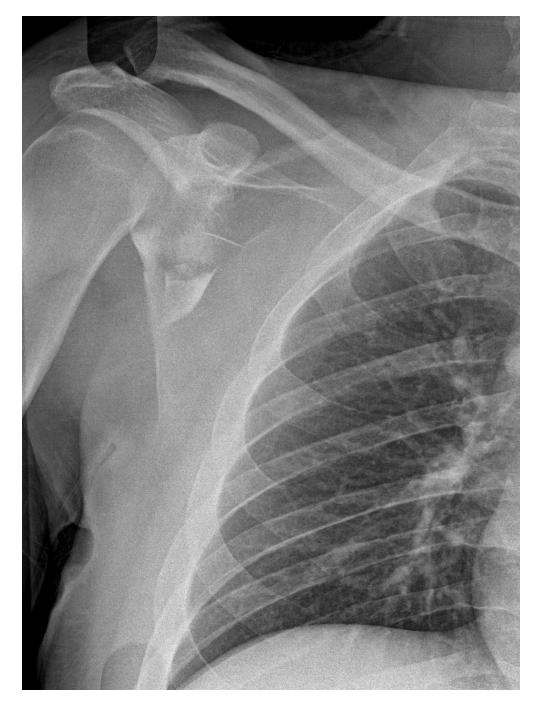

3) Scapular Fractures

Accounts for 3-5% of acute shoulder fractures seen in emergency departments (6).

Risk Factors / mechanism : High-energy trauma (i.e. high speed MVC)

Evaluation often requires CT imaging, usually associated with other injuries (rib fractures, lung injury, etc)

Fracture Patterns

Scapular Body (45-50%)

Scapular body fractures are rarely unstable, and can almost always be managed nonoperatively

Scapular body fractures indicate high-energy mechanism, and co-occur with thoracic injury (rib fractures, pulmonary contusion, pneumothorax) 21-22% of the time (17)

Glenoid Fossa (35%)

Highly variable

Glenoid rim fractures are usually caused by acute shoulder dislocation

Intraarticular fractures should be evaluated with CT imaging

Processes: Coracoid, Acromion (15%)

Acromion fractures can result in subacromial impingement syndrome

ED Management: The vast majority of isolated scapula fractures are managed nonoperatively. Intraarticular glenoid fractures and process fractures may require cross-sectional imaging and operative repair; however, this rarely needs to occur on an emergent basis and most patients can safely be discharged from the emergency department with a sling. Fractures of the scapular body indicate high-energy trauma, and the patient MUST be evaluated for additional intrathoracic injury (rib fractures, pneumothorax, pulmonary contusion, blunt cardiac injury, etc). CT imaging of the thorax is generally indicated for patients with scapular body fractures, and many of these patients will be admitted for 24-48 hours of observation due to the risk of concomitant intrathoracic injury (6,17).

It is important to remember that fractures involving the scapula and ipsilateral clavicle are at high risk for scapulothoracic dissociation. This limb-threatening condition occurs when the entire shoulder girdle separates from the thorax, usually with lateral distraction. This poses high risk to neurovascular structures, and emergent orthopedics consultation is required (18).

Shoulder Dislocations

Account for 13-17% of acute shoulder injuries seen in the Emergency Department (1,2).

Shoulder dislocations are common, representing 13-17% of traumatic shoulder injuries seen in emergency departments (1). Please see consultant corner posts (Part One, Part Two). for an in-depth discussion on acute management of the dislocated shoulder in the emergency department.

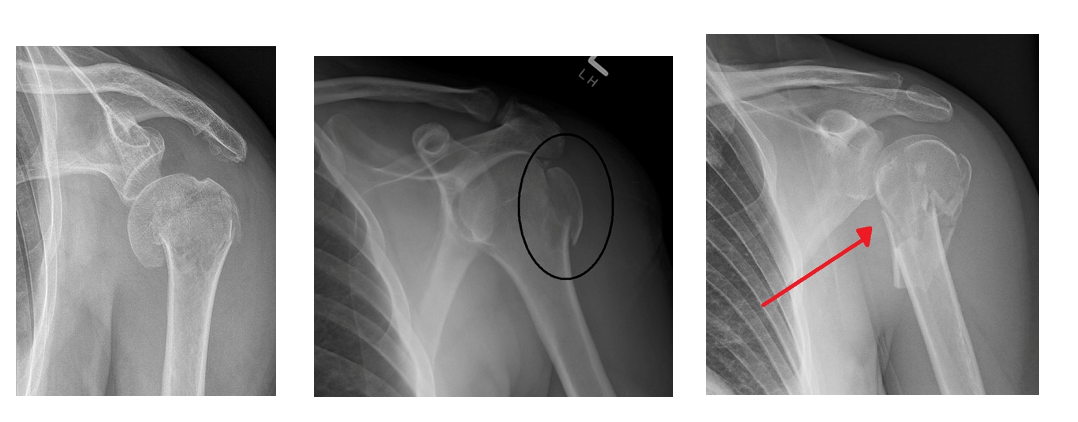

Anterior dislocation

Most common: Accounts for >95% of acute shoulder dislocations

Generally results from direct impact

Posterior Dislocation

Less common: Accounts for 2-4% of acute shoulder dislocations

Generally results from muscle spasm seen with seizure, electrocution

Inferior dislocation

Extremely rare: Accounts for <1% of acute shoulder dislocations

Typically results from hyperabduction

Shoulder dislocations are often associated with impaction fractures of the humeral head (Hill-Sachs fracture) and/or the glenoid rim (Bankart lesion).

ED Management: Most shoulder dislocations can undergo closed reduction and discharge from the emergency department in a sling with orthopedics follow-up. Many techniques exist for closed reduction. Analgesia can often be accomplished with an intraarticular block, but sometimes systemic procedural sedation is required. Generally, dislocations associated with fracture of the humeral head should still undergo attempt at closed reduction. If reduction cannot be achieved, emergent orthopedics consultation is indicated (7,8).

Soft Tissue Injuries

Account for 45-48% of acute shoulder injuries seen in the Emergency Department (1,2)

1) Acromioclavicular Separation

The scapula attaches to the lateral end of the clavicle via the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments. Disruption of this complex results in separation of the acromion process and the clavicle, termed acromioclavicular (AC) separation. Severity ranges from partial tear of the acromioclavicular ligament without instability (Rockwood Type I classification) to complete rupture of the acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular ligaments with superior (type IV/V) or inferior (Type VI) displacement of the clavicle.

Mechanism: Generally caused by direct impact

ED management: Generally, can be placed in a sling and discharged from the emergency department with orthopedic follow-up. Rockwood Type I-III are generally managed nonoperatively, while Types IV-VI often require surgery. Emergent orthopedics consultation is usually not indicated and reserved for cases of severe associated injury or evidence of neurovascular compromise (6).

2) Rotator Cuff Injuries

There are many muscles and tendons involved in the shoulder girdle and shoulder proper. The most common tendinous injuries in patients usually involve the rotator cuff muscles. This musculotendinous complex consists of four muscles—the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis, and teres minor. Injuries range from mild overuse tendinopathy to full-thickness tears to one or more of these tendons. The most commonly injured rotator cuff tendon is the supraspinatus (14).

Mechanism: Shoulder movement in unstable position, often co-occurs with shoulder dislocation

Risk Factors: Old age (>60), activities that place the shoulder in unstable positions (throwing activities, rowing, rock climbing, etc)

Provocative physical exam maneuvers

Supraspinatus Tear

Difficulty with initial 15 degrees of shoulder flexion (Drop arm test, positive Jobe/Empty Can Test)

Infraspinatus Tear

Difficulty with external rotation at 0 degrees of abduction (ER lag sign)

Teres Minor Tear

Difficulty with external rotation at 90 degrees of abduction (Hornblowers sign)

Subscapularis Tear

Difficulty with internal rotation at 0 degrees of abduction (IR lag sign) (14,15)

ED Management: Most rotator cuff injuries can be placed in a sling and discharged from the emergency department with orthopedics follow-up. The diagnosis will rarely be made in the emergency department, as MR is generally the gold standard for diagnosing soft tissue injuries of the shoulder. Emergency department management involves physical exam maneuvers, occasionally ultrasound, a neurovascular assessment, and X-ray imaging to exclude concomitant fracture and dislocation. Emergent orthopedics consultation is generally not indicated (7,16).

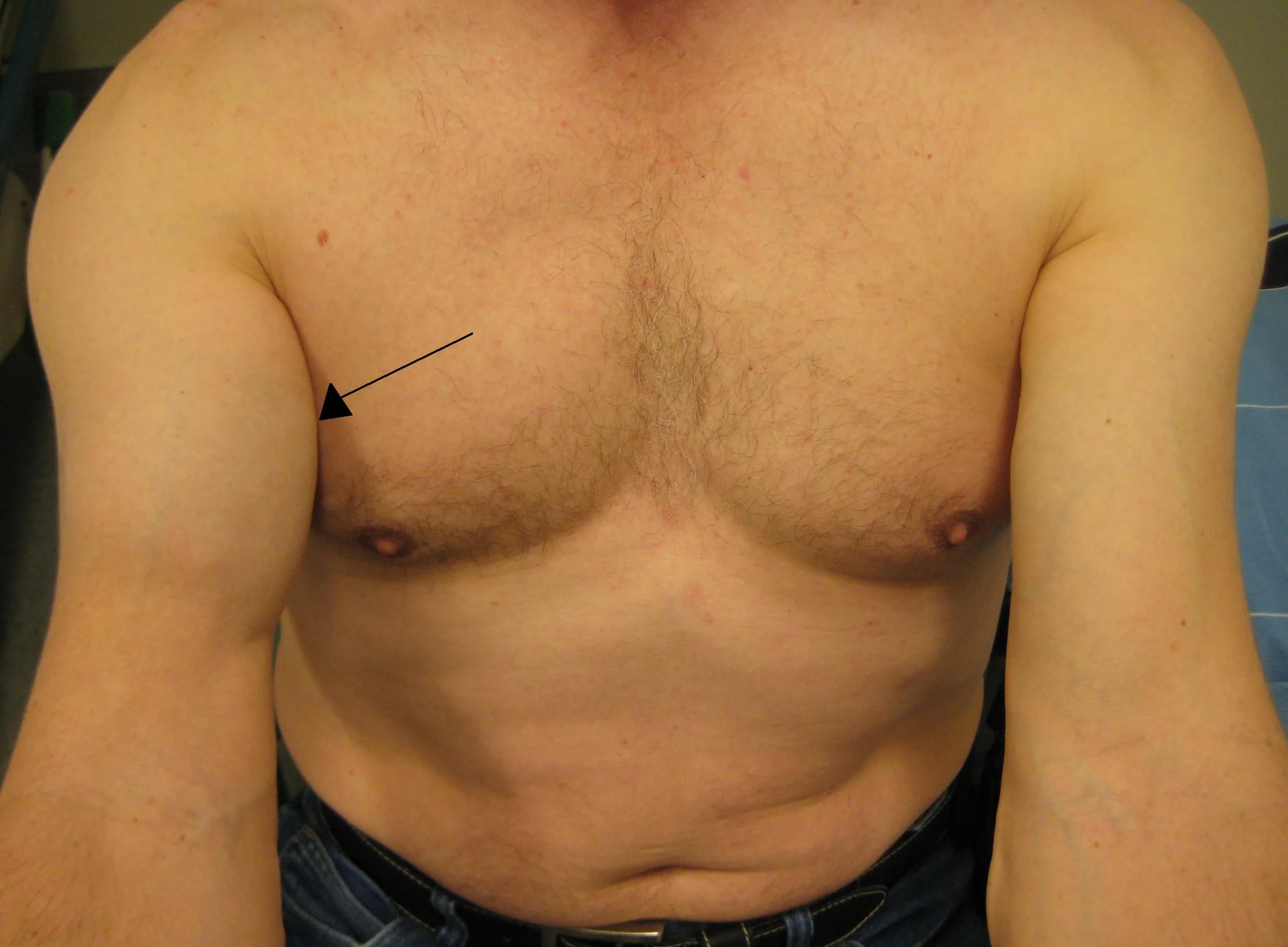

3) Biceps Tendon Tear

Mechanism: Resisted elbow flexion, often co-occurs with rotator cuff injury

Risk factors: Old age, activities that place large forces on the biceps brachii (weight-lifting, bicep curls)

Provocative physical exam maneuvers

Pain with resisted supination of the forearm

Biceps asymmetry when compared to the contralateral arm (Popeye sign)

ED Management: Similar to rotator cuff injuries, most (suspected or diagnosed) biceps tendon tears can be managed in the ED with a sling and orthopedics follow-up without emergency consultation at the time of injury.

4) Injuries to the Labrum

The labrum is a fibrocartilage ring that lines the glenoid fossa to provide cushion and extend the articular surface of the shoulder joint. Injuries to the labrum are common and often coincide with other acute shoulder injuries to include rotator cuff tears and shoulder dislocations. The symptoms can range from mild pain to severe a catching and popping sensation while the joint is ranged.

Risk Factors: old age, activities that place the shoulder in unstable positions (throwing activities)

Mechanism: Often caused by subluxation or dislocation of the shoulder joint, direct impact, or overuse

Labrum Tear Patterns

Posterior tears—Most common. Most common symptom is pain

Anterior tears—Less common. Most common symptom is a sensation of joint instability

Superior tears—The “SLAP” tear (superior labrum, anterior-to-posterior) is a specific pattern that often follows shoulder subluxation/dislocation. Superior labral tears are more likely to require operative repair than other types of labral tears. This is because the short head of the biceps tendon partially originates on the superior labrum, making it integral in structure of this complex (9,10).

ED Management: As with suspected rotator cuff tears, suspected labral tears can generally be placed in a sling for comfort and discharged from the emergency department with orthopedics follow-up. ED management again involves a detailed physical exam, neurovascular assessment, and X-ray imaging to rule out acute osseous injury.

5) Adhesive Capsulitis

Adhesive capsulitis, also known as frozen shoulder, involves complex chronic pathophysiology that ultimately results in fibrosis, adhesions, and immobility within the glenohumeral joint. Primary adhesive capsulitis develops spontaneously and cannot be attributed to a traumatic injury or immobility. Secondary adhesive capsulitis is more common and generally occurs following traumatic shoulder injury and subsequent extended immobility (11).

Risk Factors: Diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, metabolic syndrome, age >60, prolonged shoulder immobility

Symptoms: gradual onset of joint pain, stiffness, and ultimately immobility

Exam: Unlike other acute shoulder pathology, adhesive capsulitis is characterized by decreases in both active and passive range of motion (11,12)

Treatment: Physical therapy, increasing range of motion exercises, occasionally surgical lysis of adhesions

ED Management: The treatment of adhesive capsulitis in the emergency department setting is rare. Given its insidious onset, treatment should involve optimization of comorbidities (glycemic control, euthyroidism), ROM exercises, and a referral to orthopedics. There is, however, an emergency provider role in the prevention of adhesive capsulitis. Given the condition’s association with shoulder immobility, it is important to counsel patients regarding the risk of developing adhesive capsulitis any time they are placed in shoulder immobility (i.e. sling) for another acute shoulder pathology. Patients should be encouraged to remove their sling daily and allow for some passive range of motion (such as letting their arm hang and swing in small circles). This should be limited by pain, and care should be taken in patients with significant fractures involving the humeral head or glenoid fossa (13).

Summary

The shoulder joint is a complex structure, and acute injuries can range from mild tendinopathies to severe fracture-dislocations that require emergent surgical intervention. It is incumbent upon the emergency clinician to evaluate for these severe injuries, as many carry significant morbidity. General management in the emergency department involves a thorough physical examination, neurovascular assessment, radiographic imaging, symptom control, and an orthopedics referral. Additional adjuncts such as ultrasound, cross-sectional imaging, provocative maneuvers, and closed reductions can be employed as needed based on this initial evaluation. Most shoulder injuries are safe to be discharged from the emergency department with orthopedics follow-up; however, injuries resulting in irreducible shoulder dislocations, open fractures, scapular fractures, and evidence of neurovascular compromise all warrant emergent specialist involvement and may necessitate admission to the hospital for monitoring or surgical intervention.

POST BY Solomon Sindelar, MD

Dr. Sindelar is a PGY-1 resident at the University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine Residency.

EDITING BY ANITA GOEL, MD

Dr. Goel is an Associate Professor at the University of Cincinnati, a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2018, and an assistant editor of Taming the SRU.

REFERENCES

Reiad TA, Peveri E, Dinh PV, Owens BD. Epidemiology of Shoulder Injuries Presenting to US Emergency Departments. Orthopedics. 2025;48(2):e81-e87.

Enger M, et al. Shoulder injuries from birth to old age: A 1-year prospective study of 3031 shoulder injuries in an urban population. Injury. 2018;49(7):1324-9.

Triplet J. Proximal Humerus Fracture. OrthoBullets. Updated 22 Oct 2025. Accessed 8 Jan 2026.

Pecci M, Kreher, JB. Clavicle Fractures. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):65070.

Serpico M, Tomberg S. The emergency medicine management of clavicle fractures. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;49:315-25.

Myers D, Weatherford B. Scapula Fractures. OrthoBullers. Updated 30 Jan 2025. Accessed 8 Jan 2026.

Simon LM, Nguyen V, Ezinwa NME. Acute Shoulder Injuries in Adults. Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(5):503-12

LeBrun D. Anterior Shoulder Dislocation. OrthoBullets. Updated 27 Dec 2021. Accessed 8 Jan 2026.

Alexeev M, Kercher JS, Levinia Y, Duralde XA. Variability of glenoid labral tear patterns: a study of 280 sequential surgical cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30(12):2762-6.

Steffes MJ, McCullock PC. SLAP Lesions. OrthoBullets. Updated 31 May 2025. Accessed 9 January 2026.

Sarasua SM, Floyd S, Bridges WC, Pill SG. The epidemiology and etiology of adhesive capsulitis in the U.S. Medicare population. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):828

Mullen JP, Hauer TM, Lau EN, Lin A. Adhesive Capsulitis of the Shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2025;41(7):2176-8.

Steffes MJ. Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Shoulder). OrthoBullets. Updated 18 April 2025. Accessed 9 January 2026.

Bedi A, et al. Rotator Cuff Tears. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10(1):8.

Levine W. Rotator Cuff Tears. OrthoBullets. Updated 28 April 2025. Accessed 9 January 2026.

Alraddadi A, et al. The association between a rotator cuff tendon tear and a tear of the long head of the biceps tendon: Chart review study. PLoS One. 2024;19(3):e0300265.

Brown C, Elmobdy K, Raja AS, Rodriguez RM. Scapular Fractures in the Pan-scan Era. Acad Emerg med. 2018;25(7):738-43.

Jones T, Szatkowski J. Scapulothoracic Dissociation. OrthoBullets. Updated 13 September 2021. Accessed 9 January 2026.