Consultant Corner: Acute Management of the Dislocated Shoulder, Part 2

/Shoulder dislocations are a bread-and-butter emergency medicine presentation—common, painful, and often deceptively complex. As the most frequently dislocated large joint, the shoulder demands a confident, systematic approach from every emergency physician. With a wide range of injury patterns, reduction techniques, and potential complications, mastering the management of shoulder dislocations is essential not only for successful reduction but also for preventing long-term morbidity. In this post which is PART TWO of the series, we will discuss pain management with intra-articular lidocaine in addition to a variety of reduction techniques with included videos. See PART ONE of this series for more general information on background / epidemiology, anatomy, history and physical exam, and imaging techniques.

pain management with Intra-Articular Shoulder Block

Studies have shown shoulder dislocations can be reduced with the use of intra-articular anesthetic in the acute setting. However, the use of an isolated shoulder block may be difficult in patients that are unable to relax, experiencing muscle spasms, or are further out from their time of injury. There are three methods of performing an injection to access the glenohumeral joint – anterior, posterior, and lateral. All of these approaches can be done through either landmark-guided or ultrasound-guided techniques. As there are multiple other spaces present in the shoulder (subacromial space, acromioclavicular joint), it is important to ensure that the injection goes into the glenohumeral joint to improve outcomes for reduction.

Original footage with Dr Simpson (orthopedic surgeon) and Dr Brower (ER physician) and our UCMC medical students as patients.

For all of these techniques, positioning involves having the patient sitting upright on the stretcher or in a chair. The different approaches are all reliable with regards to access to the glenohumeral joint with varying success numbers based on different cadaver testing (24). When performing a landmark-based block, it is often easy to palpate the divot in the glenohumeral joint when the shoulder is dislocated.

To enter the glenohumeral joint anteriorly, one can palpate the patient’s coracoid process and insert the needle just one finger-breadth lateral to the coracoid aiming distally and inferiorly. Even with the humeral head dislocated, the bony landmark of the coracoid is unchanged, which should allow ease of access into the glenohumeral joint.

To perform a posterior injection, one can palpate the soft spot posteriorly, which is typically 2cm distal and 2cm medial to the posterolateral border of the acromion. The needle should be aimed anteriorly towards the coracoid process, which one can palpate with their other hand to aim in that direction.

For the lateral approach, palpate to the edge of the acromion and then go ~2 cm below it where you should be able to feel the lateral sulcus, which is a groove created when the humeral head is dislocated from the glenoid. This will be your site of injection (16). This lateral approach “alternative technique”, which is more often used by emergency physicians, is seen in this companion video in addition to the anterior and posterior techniques.

Once you have identified the site of injection, take your spinal needle and enter the joint at your chosen location, aspirating as you advance. Upon entering the joint capsule, you should get a blush of blood from a hemarthrosis similar to when performing a hematoma block. You can then inject your anesthetic as discussed above.

Of note, this is a sterile procedure and the site of injection should be prepped with chlorhexidine or betadine. Typically, this procedure is performed with a 20 or 22-gauge 3.5 cm needle (i.e., a spinal needle). Using a spinal needle is essential, as traditional needles will often not reach the glenohumeral joint. Lidocaine 1% without epinephrine or bupivacaine without epinephrine are the most commonly used anesthetics for this block and always ensure to calculate the maximum safe weight-based dosing before proceeding with the block (see MDCalc for a useful calculator) (16). This is especially imperative in polytrauma patients who may be requiring local anesthetic for other procedures. Typically, 10 mL of anesthetic will be injected into the joint for this procedure and you should wait 10-20 minutes before proceeding with reduction (14,17).

Two blogs summarizing an ultrasound-guided approach to intra-articular lidocaine injection can be found here: ALiEM and emDOCs. These include videos under ultrasound guidance of injection techniques as well.

Anterior Dislocation Reduction Techniques

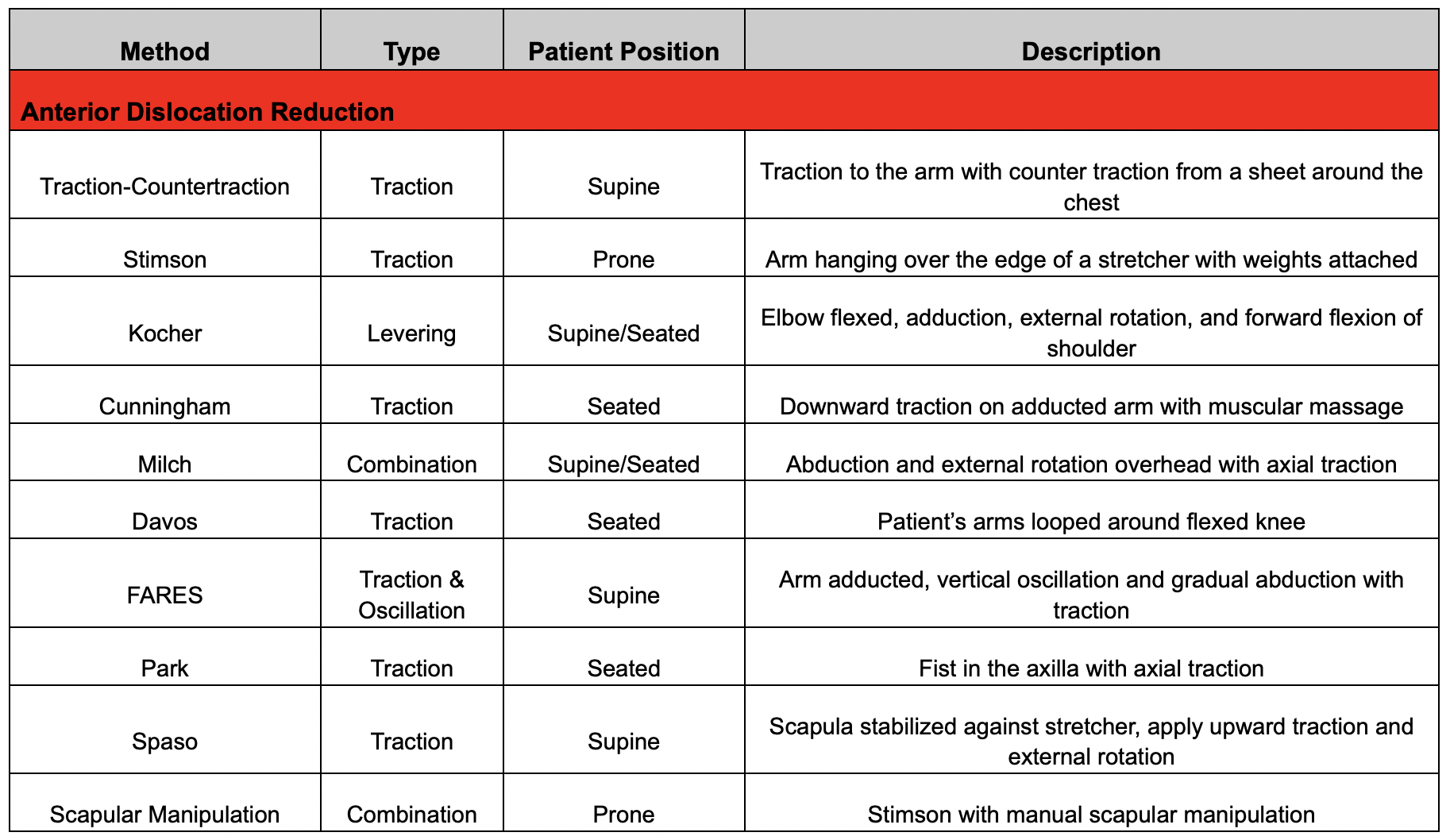

There are a plethora of reduction techniques described in the literature with a selection discussed below. However, literature has not demonstrated that any one technique is superior to another and often operators will combine multiple techniques to achieve reduction with the report success rate of achieving reduction being >90% for anterior dislocations (16,20). The key is to know several techniques well and be comfortable with them so you are facile in implementing and switching between them (16).

Below a description of these methods is a table with a summary of each method for ease of use. Videos of each maneuver are included below too.

1) Traction-Countertraction

The patient is supine and a sheet is placed around the affected axilla (over the chest and behind the back) and the affected upper extremity is pulled inferiorly and laterally at about a 45º angle. The affected upper extremity is also slowly externally rotated during the maneuver. While performing traction on the affected limb, an assistant is pulling countertraction through the sheet to aid in the reduction (1).

2) Stimson

This technique is often more successful if the arm is mildly abducted (i.e., not fully adducted and pinned to their body). The patient is placed prone with the affected shoulder hanging off the side of the bed allowing it to drop to the ground. Ensure the bed is raised enough so the hand does not touch the ground. Apply Coban or tie an ace wrap around the patient's wrist and apply weights to this apply traction to the extremity. Typically, 10-15 pounds will be sufficient and weights can be added to the wrist in 5 pound increments. If no weights are available, bags of IV fluids can be substituted. Ensure that the patient is not holding the weights in their hands as that will prevent muscle relaxation. Wait ~30 minutes to allow the joint to reduce itself. When the shoulder is reduced, the patient may feel a subjective clunk. The provider may also flex the elbow and provide some manual downward traction to aid in the reduction maneuver. Additionally, the provider can combine scapular manipulation (see #10 below) and deltoid massage to aid in reduction (1,16).

3. Kocher

This maneuver is performed with the patient seated either upright or supine. With the patient’s elbow flexed to 90º, the operator grasps the forearm at the elbow and distal humerus applying axial traction with the elbow adducted against the body. Slowly externally rotate the shoulder to 70-85º until resistance is felt. The goal is to have the hand abducted from the body and not in front of them. The shoulder is then forward flexed as far as possible by the operator with continued applied axial traction leading to reduction of the humeral head (1,16).

This maneuver is often combined with the Cunningham and Milch maneuvers (see #’s4 and 5 below) as follows. Specifically, the Cunningham maneuver can be applied prior to externally rotating the arm by massaging the trapezius, deltoid, and bicipital muscles with the other hand (or by another operator). Typically, perform massage for ~5 minutes to achieve adequate muscle relaxation. Then proceed with external rotation to 70-85º of the arm and forward flexion. If reduction is not achieved at this point, proceed with the Milch maneuver by continuing abduction of the arm raising to above their head. At this point, bring the arm forward while keeping it externally rotated before internally rotating the shoulder like a swimmer’s front crawl stroke causing the humeral head to slip back into the glenoid (16).

ORIGINAL FOOTAGE FROM DR SIMPSON (ORTHOPEDIC SURGEON) AND DR BROWER (ER PHYSICIAN) FEATURING UCMC MEDICAL STUDENTS AS PATIENTS

4) Cunningham

This maneuver is performed with the patient sitting upright with the operator standing or sitting in front of the seated patient. The patient’s arm is held adducted against the torso with the elbow flexed to 90º. Have the patient then place their hand on your shoulder. In this position, the operator should apply gentle downwards traction on the arm with one hand while massaging the trapezius, deltoid, and bicipital muscles with the other hand (this can also be performed by another operator). While doing this, instruct the patient to shrug superior and posteriorly (i.e., bring their shoulder back and push their chest out) to facilitate reduction. Typically, you will need to massage the muscles for ~5 minutes to achieve adequate relaxation (16).

5) Milch

This maneuver is performed with the patient seated upright or supine. The operator places a hand with the fingers on the superior aspect of the affected shoulder using the thumb to stabilize the dislocated humeral head in a fixed position while abducting and externally rotating the arm using the other hand. Once the arm is fully abducted into an overhead position, apply gentle axial traction to the arm and use your thumb to manipulate the humeral head over the glenoid rim. If reduction has not occured, the operator can bring the arm forward while keeping it abducted and externally rotated before internally rotating the shoulder like a swimmer’s front crawl stroke causing the humeral head to slip back into the glenoid (1,16).

6) DAVOS

This maneuver involves having the patient essentially reduce their shoulder themselves. The patient should be seated upright with the head of the stretcher at 90º. The patient should then flex their knee ipsilateral to the dislocated shoulder and loop their arms around the knee (i.e., hold the wrist of the dislocated arm with the unaffected arm). The patient’s arms can be secured using 4-inch silk tape or an ace wrap. One operator can sit on the patient’s foot to help stabilize their leg and hold their arms in place on the flexed knee. Another operator can then lower the head of the stretcher until the bed is flat and ask the patient to slowly lean their upper body back to a lying position while keeping their elbows adducted. Additional neck extension helps to create traction on the dislocated shoulder allowing it to roll forward and reduce (21).

7) FARES (Fast, Reliable, and Safe)

The patient is supine in this reduction maneuver, and an oscillating motion is performed during the entirety of the manipulation. The operator holds the patient’s wrist and hand with their arm fully extended at the elbow to provide gentle axial traction. The arm is then slowly abducted away from the body while continuously oscillating the arm ~10 cm up and down. At 90º of abduction, supinate the arm so that the palm is facing up and keep abducting until the arm is above the head (i.e., ~120º of abduction). At this point, bring the arm forward like in the Milch technique (see #5 above) (1,16).

8) Park

This maneuver is performed with the patient sitting upright with the operator standing in front of the seated patient. With the forearm supinated and the elbow flexed at 90º, the provider places their fist into the axilla of the dislocated shoulder and applies steady axial traction with the other hand while simultaneously applying adduction pressure to the lateral epicondyle of the elbow. An assistant may also manipulate the scapula to move the glenoid fossa closer to the humeral head, as well as downward counterpressure to the unaffected shoulder. This technique may require 30 seconds or more of steady pressure (see this blog post by ALiEM for some great videos of this maneuver) (22).

9) Spaso

With the patient supine, the provider stands adjacent to the affected arm holding the forearm at the wrist with the elbow fully extended. The provider then forward flexes the arm to 90º while applying gentle axial traction followed by a small amount of external rotation at the shoulder. Typically, reduction will occur spontaneously after several minutes of traction, but the provider can also use their other hand to aid in reduction by pushing the humeral head toward the glenoid. There may be a palpable or audible click when the shoulder has been reduced (see this blog post by LITFL for some great videos of this maneuver) (1,23).

10) Scapular Manipulation

In this maneuver, the patient is placed prone with the affected shoulder hanging off the side of the bed allowing it to drop to the ground (similar to the Stimson maneuver discussed above). The goal of this maneuver as noted by Neha Rauker on EM:RAP UC Max is to “tip the glenoid down and scoop up the humeral head” (i.e., internally rotating and medializing the scapula) (16). The provider uses one hand to apply gentle axial traction to the humerus while also stabilizing the superior aspect of the scapula with the thumb of that hand. Using the other hand, palpate the inferior tip of the scapula and apply medial force on the inferior angle using the thumb toward the spine. Reduction is often subtle without any palpable clunk. When multiple operators are available, this maneuver can be combined with many of the maneuvers discussed above (1,16).

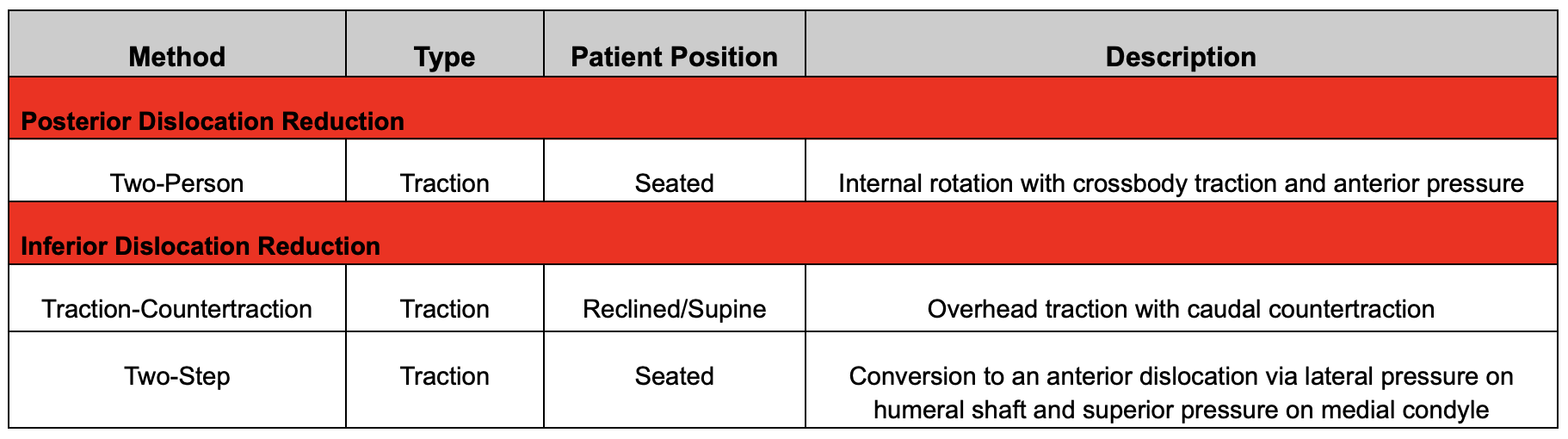

Posterior Dislocation Reduction Techniques

Posterior dislocations are rare (<3% of dislocations) (2). Moreover, diagnosis of a posterior dislocation is often difficult even with imaging. A posterior shoulder prominence may be observed with the arm in a fixed, adducted and internally rotated position (2).

For closed reduction, sedation may be required. Do not attempt reduction if 3 weeks have passed since initial injury. Additionally, closed reduction is contraindicated in patients with a humeral head defect that comprises >20% of the articular surface.

ORIGINAL CONTENT WITH DR SIMPSON (ORTHOPEDIC SURGEON) AND DR BROWER (ER PHYSICIAN) AND OUR UCMC MEDICAL STUDENTS AS PATIENTS

Closed reduction requires two persons. First, the shoulder is forward flexed to 90 degrees. Internally rotate the arm to disengage the humeral head from the glenoid rim. Maintain cross-body traction provided by the assistant, while the primary operator simultaneously applies gentle, anteriorly directed pressure to the posterior humeral head. Once achieved, the reduction is completed with external rotation. Confirmed reduction as outlined in the post-reduction management.

Inferior Dislocation Reduction Techniques

1) Traction-Countertraction

The patient is typically reclined or supine with their arm held abducted above the head. To reduce, extend the arm at the elbow and then place overhead traction in the direction of the length of the humerus. A sheet is often placed around the affected shoulder and counter-traction is pulled toward the feet. Once reduction has occurred, place the arm in adduction and supinate the forearm (1).

2) Two-Step

In this technique, an inferior dislocation is converted to an anterior dislocation and then reduced using any of the techniques discussed above. In this technique, the operator will stand at the head of the bed and will place one hand on the abducted humeral shaft and the other hand on the medial epicondyle. Conversion to an anterior dislocation involves simultaneously applying lateral pressure on the humeral shaft while pulling superiorly on the medial epicondyle. This maneuver moves the humeral head from the infraglenoid position allowing rotation anteriorly around the glenoid rim while guiding the affected arm into an adducted position (1). From here, employ any of the above anterior dislocation reduction techniques.

Post-Reduction Management

Following successful reduction, it is important to obtain post-reduction x-ray imaging to confirm appropriate reduction and to evaluate for any bony injuries such Bankart and Hill-Sachs lesions, though these are often of limited clinical significance acutely. Radiographic views to confirm reduction are an axillary view, AP, lateral and a scapular-Y view. Additionally, it is imperative to repeat and document a post-reduction neurovascular and skin exam. Specifically, ensure there is no evidence of axillary nerve injury by assessing sensation to light touch over the lateral aspect of the deltoid and have the patient fire the deltoid muscle to assess motor function (16). Older patients with dislocations have a higher rate of having a concomitant rotator cuff tear associated with their injury so documenting an appropriate exam in conjunction with a good history is important.

Place the patient in a sling-and-swathe, though some orthopedists and sports medicine physicians now believe that a simple sling can also suffice. Counsel patients that they do not need to sleep in the sling. The duration of immobilization varies depending on the literature with some resources recommending immobilization for a minimum of 3-4 weeks (1). However, other resources recommend immobilizing patients age <40 years in a sling for 10 days with patients age ≥40 years in the sling for 5-7 days only to avoid potential complications such as a frozen shoulder (16).

Typically, rehabilitation begins with isometric contractions for muscle rehabilitation and passive ROM exercises such as pendulum exercises (especially important for older patients). For ROM restrictions, patients with anterior dislocations should be advised to avoid external rotation past neutral and no abduction past 90º for the first 4-6 weeks after injury. In contrast, in posterior dislocations, restrictions involve limiting internal rotation for 4-6 weeks. Return to non-contact athletic activities is typically appropriate once the patient regains full strength and can perform ROM without pain. Timing of return to contact sports is not well studied, but a general rule of thumb is to avoid contact sports for a minimum of 2 months from the time of injury (1). Given variability in recommendations for immobilization and rehabilitation, it is important that patients have close orthopedic surgery follow-up and to agree upon these recommendations with your orthopedic surgery colleagues.

POST BY CHARLIE BROWER, MD AND NANA SIMPSON, MD WITH ASSISTANCE FROM MEDICAL STUDENTS BRI MCMONAGLE, LUKE BUCK, HAYDEN SCHOTT

Dr. Brower completed his residency in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati in June 2025 and is now an attending EM physician at North Memorial Health in Minnesota.

Dr. Simpson completed his residency in Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Cincinnati in June 2025 and is now completing a fellowship specializing in Shoulder and Elbow surgery at the University of Pittsburgh.

EDITING BY BRIAN GRAWE, MD AND BRET BETZ, MD AND DANNY GAWRON, MD AND ANITA GOEL, MD

Dr Grawe is a Professor in Orthopedic Surgery at the University of Cincinnati with fellowship training in sports medicine and shoulder reconstruction. He is also one of the team physicians for the Cincinnati Bengals.

Dr Betz is an Associate Professor in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati with fellowship training in sports medicine. He works in both the emergency department as well as the sports medicine clinic. He is also one of the team physicians for the Cincinnati Bengals.

Dr Gawron is an Assistant Professor in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati with fellowship training in sports medicine. He works in both the emergency department as well as the sports medicine clinic.

Dr. Goel is an Associate Professor at the University of Cincinnati, a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2018, and an assistant editor of Taming the SRU.

REFERENCES

Youm T, Taekmoto R, Park PKH. Acute management of shoulder dislocations. J Am Acad Ortho Surg. 2014; 22(12):761-771. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-22-12-761.

Gottlieb M. Shoulder Dislocations in the Emergency Department: A comprehensive Review of Reduction Techniques. J Emerg Med. 2020; 58(4):647-666. dot:10.1016 /j.jemermed.2019.11.031.

Zacchilli MA, Owens BD. Epidemiology of shoulder dislocations presenting to emergency departments in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(3):542-549. doi:10.2106/JBJS.I.00450.

Leroux T, Wasserstein D, Veillette C, et al. Epidemiology of primary anterior shoulder dislocation requiring closed reduction in Ontario, Canada. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(2):442-450. doi:10.1177/0363546513510391.

Kao JT, Chang CL, Su WR, Chang WL, Tai TW. Incidence of recurrence after shoulder dislocation: a nationwide database study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27(8):1519-1525. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2018.02.047.

Long B. EM@3AM: Anterior Shoulder Dislocation. emDOCs. April 4, 2020. Accessed November 16, 2024. https://www.emdocs.net/em3am-anterior-shoulder-dislocation/.

Hindle P, Davidson EK, Biant LC, Court-Brown CM. Appendicular joint dislocations. Injury. 2013;44(8):1022-1027. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2013.01.043.

Rowe CR. Prognosis in dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1956;38-A(5):957-977.

Robinson CM, Aderinto J. Posterior shoulder dislocations and fracture-dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(3):639-650. doi:10.2106/JBJS.D.02371.

Patel DN, Zuckerman JD, Egol KA. Luxatio erecta: case series with review of diagnostic and management principles. Am J Orthop Belle Mead NJ. 2011;40(11):566-570.

Soslowsky LJ, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU, Mow VC. Articular geometry of the glenohumeral joint. Clin Orthop. 1992;(285):181-190.

Robinson CM, Shur N, Sharpe T, Ray A, Murray IR. Injuries associated with traumatic anterior glenohumeral dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(1):18-26. doi:10.2106/JBJS.J.01795.

Gottlieb M, Russell F. Diagnostic Accuracy of Ultrasound for Identifying Shoulder Dislocations and Reductions: A Systematic Review of the Literature. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(5):937. doi:10.5811/westjem.2017.5.34432.

Tin J, Simmons, Cailey, Ditkowsky, Jared, Alerhand, Stephen. US Probe: Ultrasound for Shoulder Dislocation and Reduction. emDOCs.net - Emergency Medicine Education. January 18, 2018. Accessed November 16, 2024. https://www.emdocs.net/us-probe-ultrasound-for-shoulder-dislocation-and-reduction/.

Blakeley CJ, Spencer O, Newman-Saunders T, Hashemi K. A novel use of portable ultrasound in the management of shoulder dislocation. Emerg Med J EMJ. 2009;26(9):662-663. doi:10.1136/emj.2008.069666.

Rauker N, Pensa G. Shoulder Dislocations. EM:RAP UC Max. August 2024. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.emrap.org/urgent-care/episode/ucmax2024august/shoulderreducti.

Aronson, Paul L, Mistry, Rakesh D. Intra-articular lidocaine for reduction of shoulder dislocation. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(5). doi:10.1097/PEC.0000000000000131.

EM:RAP Productions. Intra-articular Lidocaine For Reduction Of Shoulder Dislocation. Accessed May 5, 2025. https://www.emrap.org/episode/ema-2015-1/abstract22.

Rungsinaporn V, Innarkgool S, Kongmalai P. Is Ultrasound-guided or Landmark-guided Intra-articular Lidocaine Injection More Effective for Pain Control in Anterior Shoulder Dislocation Reduction? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Orthop. 2024;482(7):1201-1207. doi:10.1097/CORR.0000000000002936.

Hayashi M, Tanizaki S, Nishida N, et al. Success rate of anterior shoulder dislocation reduction by emergency physicians: a retrospective cohort study. Acute Med Surg. 2022;9(1):e751. doi:10.1002/ams2.751.

Stafylakis D, Abrassart S, Hoffmeyer P. Reducing a Shoulder Dislocation Without Sweating. The Davos Technique and its Results. Evaluation of a Nontraumatic, Safe, and Simple Technique for Reducing Anterior Shoulder Dislocations. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(4):656-659. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2016.01.020.

Lin M. Trick of the Trade: Got a shoulder dislocation? Park it. ALiEM. June 25, 2013. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://www.aliem.com/trick-of-the-trade-got-a-shoulder-dislocation-park-it/.

Long N. Spaso technique. Life in the Fast Lane (LITFL). March 13, 2019. Accessed June 19, 2025. https://litfl.com/spaso-technique/.

Tobola, A., Cook, C. et al. Accuracy of glenohumeral joint injections: comparing approach and experience of provider. Journal of Shoulder & Elbow Surgery, 20(7): 1147-1154.

Bao MH, DeAngelis JP, Wu JS. Imaging of traumatic shoulder injuries - Understanding the surgeon's perspective. Eur J Radiol Open. 2022 Mar 2;9:100411. doi: 10.1016/j.ejro.2022.100411. PMID: 35265737; PMCID: PMC8899241.

Dickens, J., Slaven, S., Cameron, K. et. al. (2019). Prospective Evaluation of Glenoid Bone Loss After First-time and Recurrent Anterior Glenohumeral Instability Events. American Journal of Sports Medicine, 47(5): 1082-1089. doi: 10.1177/0363546519831286.