Ovarian Emergencies: Adnexal Ectopic Pregnancy

/Adnexal pregnancy is an uncommon but high‑stakes emergency that demands careful attention in the emergency department. Because its clinical features often overlap with other early pregnancy or pelvic conditions, recognition hinges on vigilance and thoughtful evaluation. In this post, we’ll walk through the key aspects of adnexal pregnancy — from how it presents, to the diagnostic strategies that help distinguish it, to the management approaches that safeguard patient outcomes. By isolating this topic from other adnexal pathologies, we aim to provide a clear, focused discussion of its unique challenges and critical implications.

Overview

An ectopic pregnancy is when an embryo implants outside of the endometrial cavity. A tubal ectopic pregnancy is by far the most common location, accounting for approximately 95% of cases. Less common locations include the myometrium, ovary, cervix, cesarean scar and peritoneum. In this post, we will discuss adnexal ectopic pregnancies, which represent about 1-3% of all ectopics as quoted by different sources. 2% of all pregnancies result in an ectopic with a mortality rate of around 3%.

Although 98% of pregnancies result in an IUP and thus only about 2% result in an ectopic pregnancy, for women presenting to the emergency department with first trimester vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain, the incidence is much higher —> occurring in as many as 1 in 6 women. Commonly described risk factors include advanced maternal age, smoking, fallopian tube abnormalities (congenital, prior surgery), history of pelvic inflammatory disease, prior ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy due to contraceptive failure, and active use of fertility medications for use in IVF. Although women who have an IUD have an overall lower risk of ectopic pregnancy, if they do become pregnant the chance of it being an ectopic can be as high as 50% depending on the type of IUD.

Please refer to this accompanying post for more comprehensive information on ectopic pregnancies (not just adnexal), and appropriate algorithms and ultrasound imaging concepts for emergency department work up. The rest of this post is focused on only adnexal ectopic pregnancies, although a lot of the information applies to other types of ectopic pregnancies as well.

Presentation and Examination

Unruptured ectopic

Typical symptoms: lower abdominal/pelvic pain and vaginal bleeding with positive home pregnancy test

Red flags in the history that should raise suspicion for an ectopic:

Early positive home pregnancy test without confirmed intrauterine pregnancy (IUP)

Preceding amenorrhea ≥4 weeks

Current IVF treatment

Exam findings:

Cervical motion tenderness

Adnexal tenderness or palpable adnexal mass

Associated pregnancy symptoms: nausea, breast tenderness

Ruptured ectopic

Acute, severe abdominal pain with possible:

Nausea, vomiting, dizziness, syncope

Referred shoulder pain (phrenic nerve irritation from hemoperitoneum)

Urinary symptoms

May follow asymptomatic period or dull/colicky pain ± vaginal bleeding

Vital sign abnormalities: tachycardia, hypotension (depending on bleeding severity)

Exam findings: abdominal guarding, rigidity, rebound tenderness → suggestive of hemoperitoneum

Diagnosis

Initial work-up in a well-appearing patient):

Speculum exam (rules out infection or pregnancy loss, less useful for ectopic diagnosis)

Labs: quantitative beta-hCG, CBC, type & screen

Imaging: pelvic ultrasound (transabdominal + transvaginal)

Initial work up in unstable patients / suspected rupture:

FAST exam to assess free fluid in rectouterine pouch or hepatorenal recess → expedite GYN consult for likely surgery

If no significant free fluid on FAST exam, can proceed with speculum / labs / imaging as above without immediate GYN consult

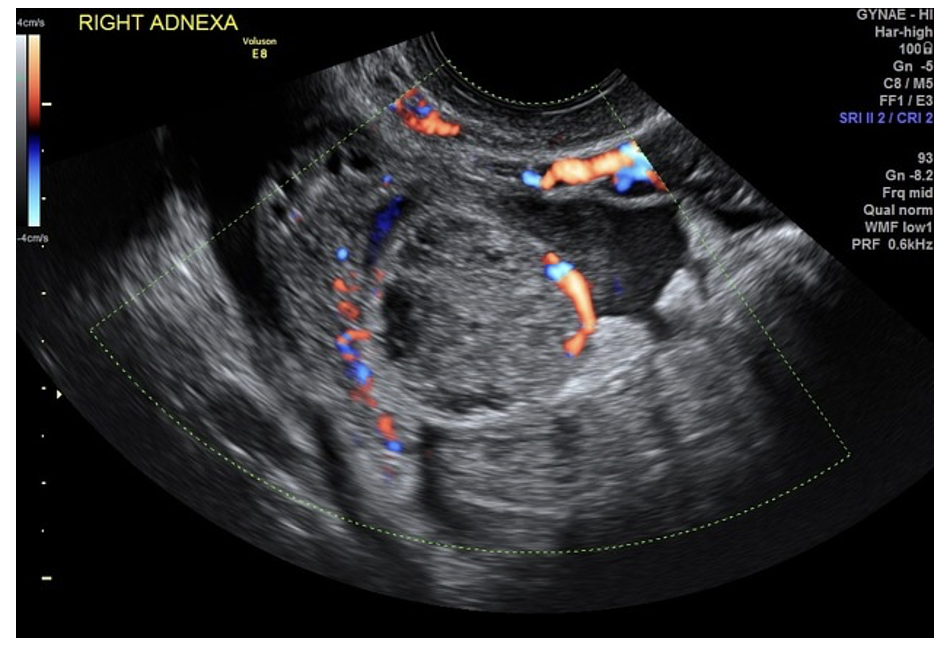

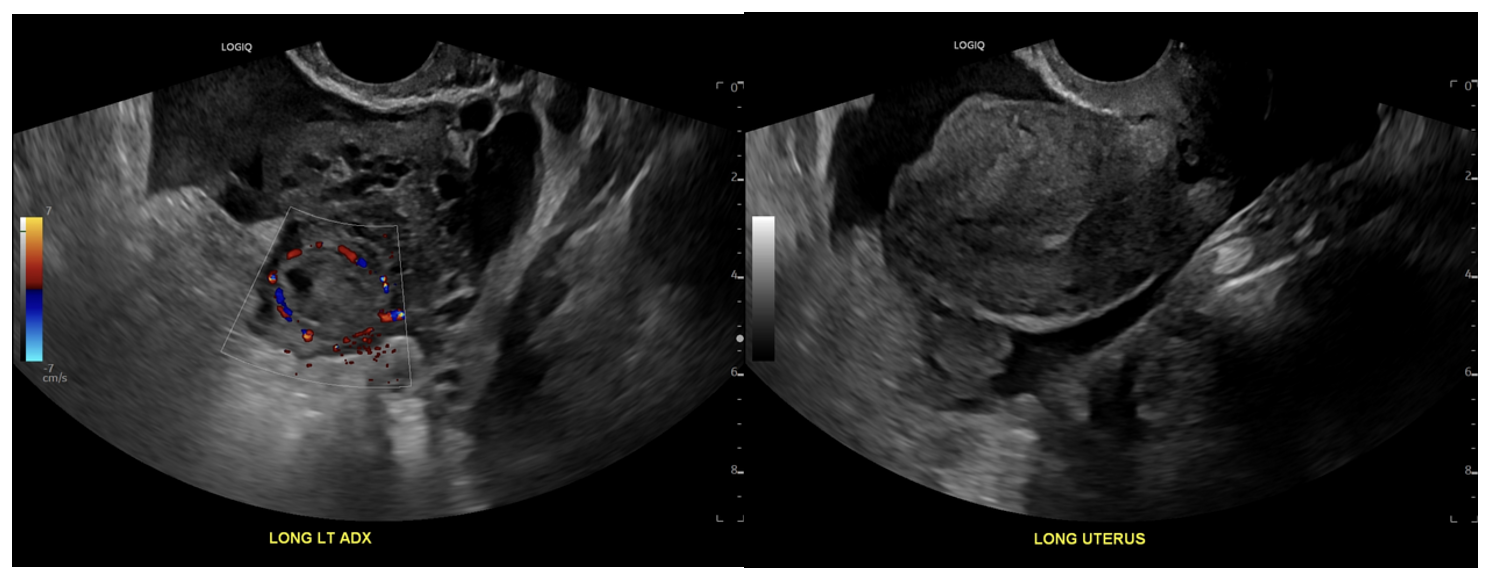

Ultrasound findings:

IUP: gestational sac + yolk sac in uterus

Ectopic: gestational sac + yolk sac outside uterus (rare but diagnostic)

Suggestive signs: heterogenous adnexal mass, “ring of fire” on Doppler, pseudogestational sac, tubal ring sign

Discriminatory zone:

Beta-hCG threshold above which IUP should be visible on TVUS

Commonly quoted: 1,500 mIU/mL

ACOG recommends conservative cutoff: up to 3,500 mIU/mL to avoid misdiagnosis

Management

Above discriminatory zone (>3,500 mIU/mL):

No IUP on TVUS → consider ectopic until proven otherwise

Radiology-performed ultrasound + gynecology consult for definitive management

Below discriminatory zone (<3,500 mIU/mL):

Repeat hCG in 48 hours to assess rise

Expected minimum 2-day rise (Barnhart et al., 2016):

49% if initial hCG <1,500 mIU/mL

40% if 1,500–3,000 mIU/mL

33% if >3,000 mIU/mL

Values below thresholds → suggest ectopic or early pregnancy loss → close gynecology follow-up

Summary

A key principle in evaluating suspected ectopic pregnancy is recognizing that certain historical features should heighten clinical suspicion, prompting early consideration of the diagnosis. Because hCG discriminatory values are highly variable and unreliable, clinicians should avoid waiting for a discrete threshold and instead prioritize serial pelvic ultrasounds. In unstable patients, rapid bedside ultrasound to assess for free fluid is essential, as early recognition and intervention are critical to reducing morbidity and mortality.

POST BY DALTON BANNISTER, MD

Dr. Bannister is a PGY-1 resident at the University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine Residency.

EDITING BY ANITA GOEL, MD

Dr. Goel is an Associate Professor at the University of Cincinnati, a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2018, and an assistant editor of Taming the SRU.

REFERENCES

Papageorgiou, D., Sapantzoglou, I., Prokopakis, I., & Zachariou, E. (2025). Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy: From Diagnosis to Treatment. Biomedicines, 13(6), 1465. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13061465

Vadakekut ES, Gnugnoli DM. Ectopic Pregnancy. [Updated 2025 Mar 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539860/

Hendriks, E., Rosenberg, R., & Prine, L. (2020). Ectopic Pregnancy: Diagnosis and Management. American family physician, 101(10), 599–606.

Mullany, K., Minneci, M., Monjazeb, R., & C Coiado, O. (2023). Overview of ectopic pregnancy diagnosis, management, and innovation. Women's health (London, England), 19, 17455057231160349. https://doi.org/10.1177/17455057231160349

Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (2018). ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 191: Tubal Ectopic Pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology, 131(2), e65–e77. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002464

Li, C., Zhao, W. H., Zhu, Q., Cao, S. J., Ping, H., Xi, X., Qin, G. J., Yan, M. X., Zhang, D., Qiu, J., & Zhang, J. (2015). Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy: a multi-center case-control study. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 15, 187. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-015-0613-1

Barnhart, K. T., Guo, W., Cary, M. S., Morse, C. B., Chung, K., Takacs, P., Senapati, S., & Sammel, M. D. (2016). Differences in Serum Human Chorionic Gonadotropin Rise in Early Pregnancy by Race and Value at Presentation. Obstetrics and gynecology, 128(3), 504–511. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001568

Doubilet, P. M., & Benson, C. B. (2011). Further evidence against the reliability of the human chorionic gonadotropin discriminatory level. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, 30(12), 1637–1642. https://doi.org/10.7863/jum.2011.30.12.1637

Connolly, A., Ryan, D. H., Stuebe, A. M., & Wolfe, H. M. (2013). Reevaluation of discriminatory and threshold levels for serum β-hCG in early pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology, 121(1), 65–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0b013e318278f421

Ko, J. K., & Cheung, V. Y. (2014). Time to revisit the human chorionic gonadotropin discriminatory level in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. Journal of ultrasound in medicine : official journal of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, 33(3), 465–471. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.33.3.465

Budorick N, Ovarian ectopic pregnancy. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-208112

Knipe H, Tubal ectopic pregnancy. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-36812.