Ovarian Emergencies: Can't Miss Diagnoses

/While ovarian pathologies represent a minority of gynecologic presentations in the emergency department, many carry the potential for significant morbidity and mortality. Timely diagnosis often requires a high index of suspicion given their variable presentations. This article will review the presentation, diagnosis, and management of three key adnexal emergencies: ovarian cysts, ovarian torsion, and tubo‑ovarian abscesses. Although tubal ectopic pregnancy is another critical adnexal pathology, its complexity and importance warrant a dedicated discussion. We will cover ectopic pregnancy in a separate post to give it the focused attention it deserves.

Relevant Gynecologic Anatomy

The ovary is a small reproductive organ that sits inside the abdomen on either side of the uterus. It’s connected to the uterus by the utero-ovarian ligament and anchored to the pelvic wall by another ligament that also carries the ovarian blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. Together, the ovary and fallopian tube are often referred to as the “adnexa.”

At the far end of the fallopian tube is the infundibulum, which opens into the abdominal cavity. Finger-like projections called fimbriae drape over the ovary and help guide an egg into the tube after it release. From there, the tube widens into the ampulla and then narrows again at the isthmus before joining the uterus.

The details of this anatomy become especially important when pathology strikes, since the ovary’s position and blood supply influence both the presentation and the urgency of care.

1) Ovarian Cysts

Quick Overview

Occur in ~20% of women; most are asymptomatic and don’t need evaluation.

Types:

Functional cysts: physiologic, tied to menstrual cycle.

Pathologic cysts: due to cell overgrowth; can be benign or malignant.

Benign features:

Unilocular, thin-walled, no solid components, no internal blood flow → usually regress spontaneously.

Concerning features:

10 cm or symptomatic → may need surgical removal.

Large, multiloculated, solid components, or internal blood flow → higher risk of malignancy → urgent GYN referral.

Presentation and Exam Findings

Typical symptoms (especially with larger cysts):

Unilateral dull pelvic or lower abdominal pain/pressure

Dull ache in lower back or flanks

Bladder/bowel pressure → urinary urgency/frequency or constipation

Dyspareunia or dysmenorrhea → think endometrioma

Hormonally active cysts → abnormal uterine bleeding (heavy periods, spotting)

Problems you may encounter:

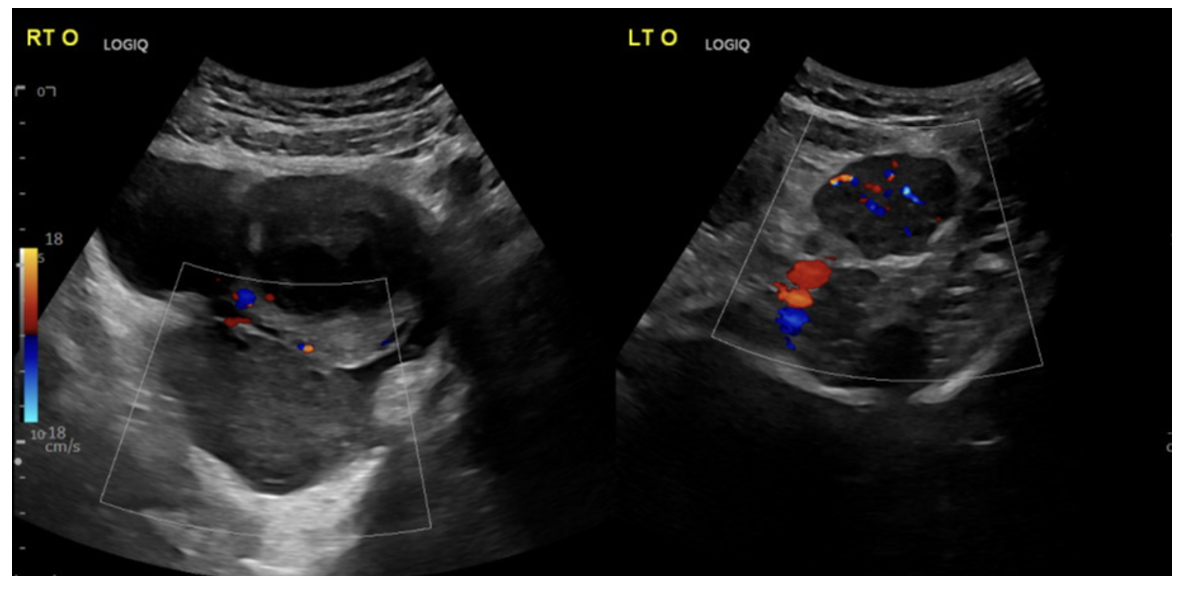

Cyst rupture / hemorrhage

Very common, often activity‑related (exercise, intercourse)

Pain shifts from dull/intermittent → sudden sharp pain

Usually self‑limited, but hemorrhagic rupture can cause hemoperitoneum, chemical peritonitis, or rarely hemorrhagic shock

Ovarian torsion (covered below in #2 in more detail)

Less common but far more serious, more likely to happen when cyst > 5 cm

Can cut off blood supply to the ovary → surgical emergency

Must be recognized quickly to preserve ovarian function

Physical exam essentials:

Abdominal exam: tenderness to palpation, peritoneal signs (sometimes)

Pelvic exam:

Speculum: check for vaginal bleeding or discharge

Bimanual: adnexal mass/tenderness, cervical motion tenderness

Diagnostic Considerations

First-line imaging (per ACOG):

Pelvic ultrasound is the initial test for suspected adnexal masses.

Use both transabdominal and transvaginal views to assess for masses or free fluid.

Ultrasound technique tips (radiology-performed is current gold standard for ovarian pathology other than ectopic, this may change in the practice environment as ultrasound skills continue to grow within the ER community over the next 5-10 years):

Transabdominal → best with a full bladder.

Transvaginal → best after bladder emptying.

Color Doppler → helpful if concerned for ovarian torsion or ectopic pregnancy.

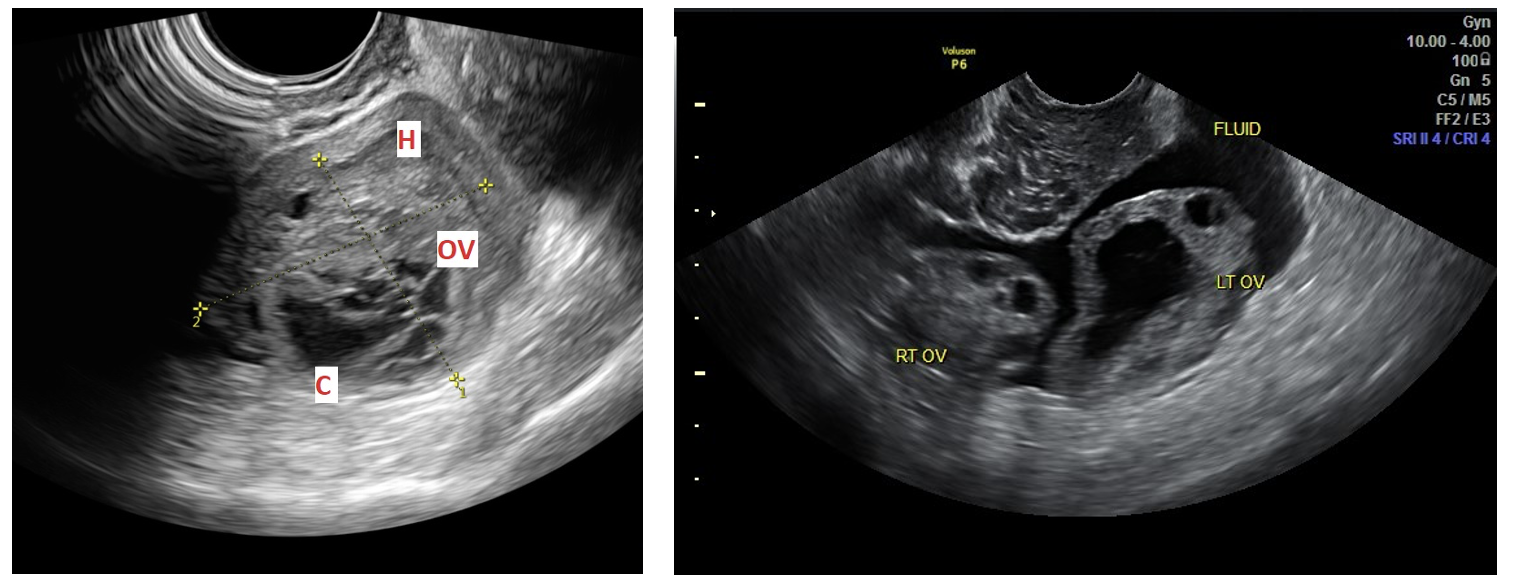

Ultrasound appearance of cysts:

Simple cysts: thin-walled, anechoic, no septations.

Complex cysts: multilocular, thickened walls, mixed solid/cystic components.

Laboratory testing (to rule out alternative etiologies):

CBC and chemistry panel

Serum/urine pregnancy test

Urinalysis

Cervical STI swabs / wet prep

Cross-sectional imaging (CT/MRI):

Consider if alternative diagnoses are suspected (e.g., appendicitis, nephrolithiasis).

Management of Ovarian Cysts

Symptomatic treatment should include multimodal pain control and antiemetics. For uncomplicated cysts regardless of appearance, discharging home with outpatient gynecology follow-up is typically appropriate. Those with intractable pain or vomiting may warrant an expanded work-up, gynecology consultation in the ED, and even potential admission for symptom control. A ruptured cyst with a large amount of free fluid or unstable vital signs warrants urgent gynecology consultation as does any concern for torsion or adnexal infection.

-

Differentiate the source of bleeding:

Vaginal bleeding may be from the cervix, vagina, or uterus. A speculum exam helps localize the source, which guides whether you’re thinking cyst rupture, cervical pathology, or another cause.

Rule out infection or discharge causes:

Vaginal discharge could point toward cervicitis, vaginitis, or pelvic infection rather than a cyst‑related issue.

Identify concurrent pathology:

A patient with pelvic pain and bleeding might have a ruptured cyst, but could also have ectopic pregnancy, miscarriage, or cervical lesions. Speculum exam helps narrow the differential.

-

Very common; often activity‑related (exercise, intercourse).

Pain shift from dull → sudden sharp.

Usually self‑limited; supportive care often enough.

Hemorrhagic rupture → hemoperitoneum, rare shock.

Ultrasound helps confirm rupture and exclude torsion.

2) Ovarian Torsion

Quick Overview

Definition:

Surgical emergency → ovary twists around supporting ligaments (utero‑ovarian + infundibulopelvic).

Sequence: venous outflow obstruction → congestion/edema → impaired arterial inflow → ischemia/necrosis if untreated.

Major risk factors:

Presence of an adnexal mass (especially >5 cm).

Dermoid cysts (heavier, more prone to twisting).

Epidemiology:

Most common in women of childbearing age (higher incidence of functional cysts).

More likely on the right side (longer utero‑ovarian ligament allows more rotation).

Predisposing conditions:

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

Hormonal ovulation induction for infertility (multiple/large cysts).

Pregnancy (especially 1st trimester).

Prior tubal ligation.

Presentation & Exam findings

Diagnostic challenge:

Variable presentation → up to 50% initially misdiagnosed.

Requires a high index of suspicion in women with acute pelvic pain.

Classic presentation:

Acute, severe, sharp, unilateral lower abdominal pain.

But: only ~59% report sudden onset; ~44% describe pain as crampy (Abbott & Houry, 2001).

Nausea/vomiting common.

Pain may radiate to flank or groin → can mimic renal colic.

Exam findings:

Abdominal/pelvic exam indicated but not reliable for diagnosis.

Up to ⅓ have no tenderness on exam.

Bimanual exam: ~30% report bilateral adnexal tenderness.

Poor sensitivity for detecting adnexal mass; poor inter-rater reliability (EPs and gynecologists).

Diagnostic considerations

Imaging of choice:

Ultrasound with color Doppler (transabdominal + transvaginal).

Common US findings:

Enlarged ovary.

Midline positioning of ovary.

Peripheral displacement of follicles.

Pelvic free fluid.

Heterogeneous ovarian stroma.

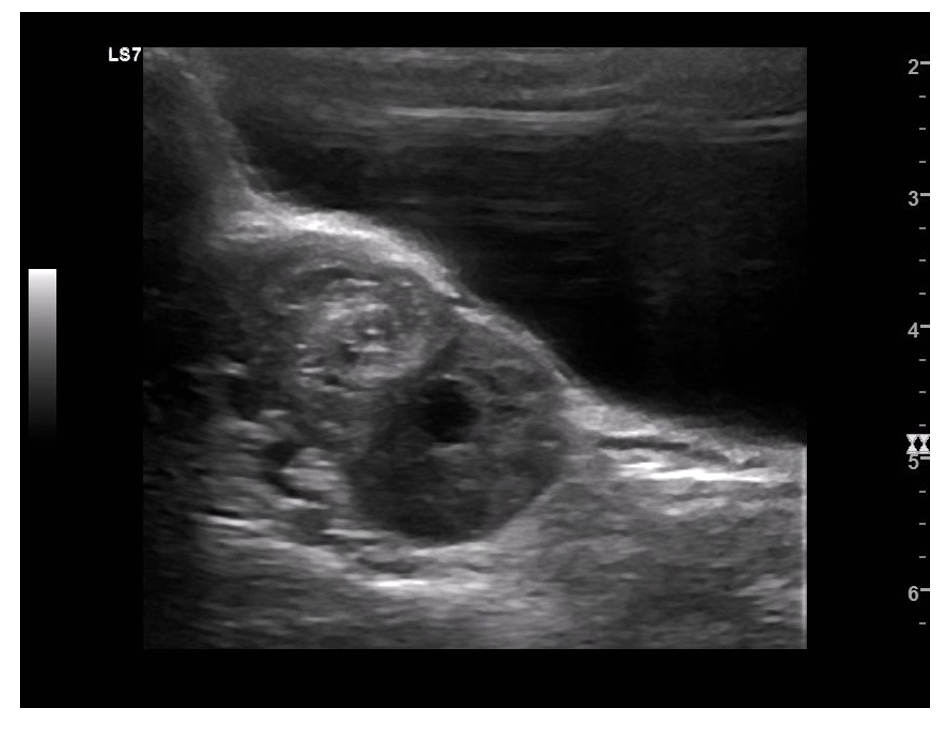

Doppler considerations:

Decreased/absent arterial flow → poor sensitivity (dual blood supply, late finding).

If present → PPV ~100%.

Key ultrasound finding:

“Whirlpool sign” (twisted vascular pedicle) (sensitivity ~65%, specificity ~91% (Garde et al., 2022))

Other modalities:

Labs and cross-sectional imaging (CT/MRI) → limited role in diagnosis.

CT/MRI may show enlarged ovary or incidental findings but not definitive.

Management

Symptomatic treatment should include multimodal pain control and antiemetics. Emergent gynecology consultation is indicated for both patients with highly suggestive imaging findings or in cases where ultrasound findings are indeterminate but there is a high index of suspicion by the ED provider.

-

Still low - sometimes quoted at only 30% chance of salvage

-

Sudden pelvic pain + nausea/vomiting → torsion until proven otherwise.

Right side more common (longer ligament).

Normal Doppler doesn’t rule it out (dual blood supply).

Whirlpool sign = highly specific → act fast.

Urgent GYN consult → time is ovary.

3) Tubo-Ovarian Abscess

Quick Overview

Definition: rare but severe complication of adnexal infection.

Most common cause: untreated pelvic inflammatory disease (ascending genital tract infection).

Other causes (less common):

Local spread (appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease).

Hematogenous spread (e.g., tuberculosis).

Pathology: inflammatory, pus‑filled mass involving fallopian tube + ovary; can extend to bowel or bladder.

Microbiology: typically polymicrobial (aerobes, anaerobes, enteric bacteria).

Risk factors:

Age 15–25.

Multiple sexual partners.

History of STIs/PID.

HIV infection.

Presentation and Exam Findings

Typical symptoms:

Fever, chills, lower abdominal pain, abnormal vaginal discharge.

~40% afebrile at presentation (large case series).

Dyspareunia and abnormal vaginal bleeding possible.

Exam findings:

Bimanual exam → unilateral/bilateral adnexal tenderness, adnexal mass, cervical motion tenderness (if PID present).

Ruptured TOA → peritonitis, sepsis.

Diagnostic Considerations

Laboratory testing:

Leukocytosis common but not universal.

Elevated inflammatory markers predict severity/treatment failure.

CRP >49.3 mg/L → 85% sensitivity, 93% specificity for TOA in hospitalized PID patients (Ribak et al., 2019).

Blood cultures if concern for rupture/sepsis.

Speculum exam → assess discharge/bleeding, obtain cervical swabs for STI screen + wet prep.

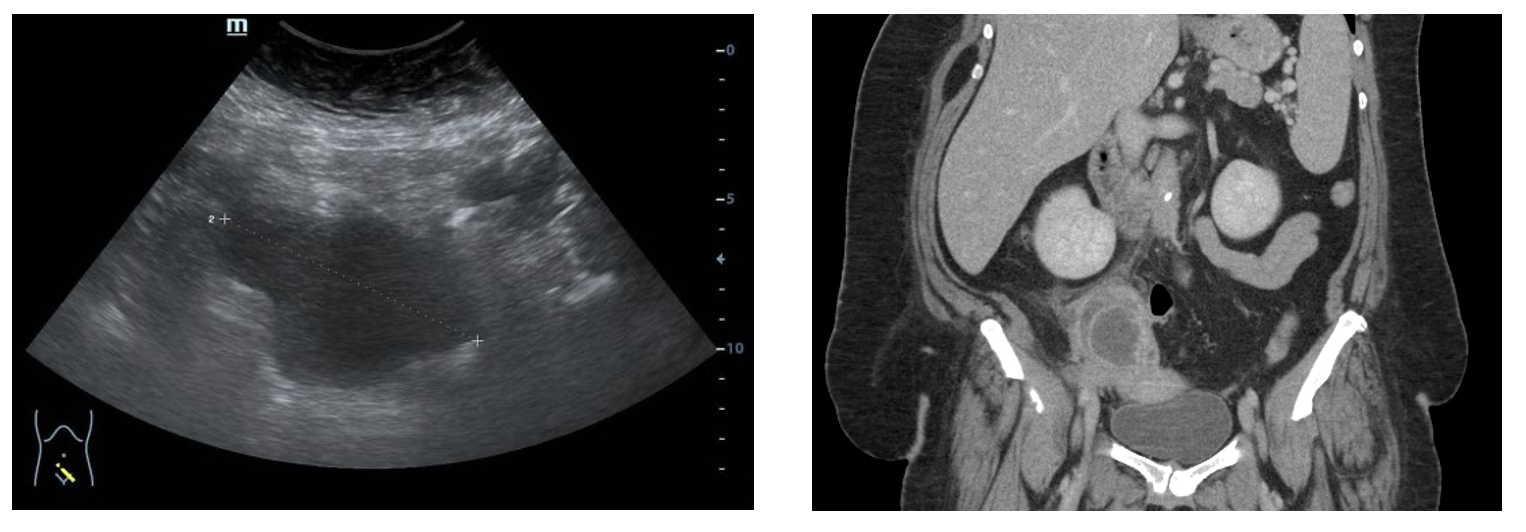

Imaging:

Pelvic ultrasound → first line.

TOA: complex, multilocular, heterogeneous mass distorting adnexal anatomy.

Dilated, thickened, fluid‑filled tubes → pyosalpinx.

Echogenic free fluid in rectouterine pouch → concern for rupture.

CT scan:

Slightly higher sensitivity than US.

Useful for ruling out alternative abdominopelvic diagnoses.

Findings: heterogeneous loculated adnexal mass, thickened rim‑enhancing walls, fat stranding, dilated tubes, pelvic free fluid.

Management

General principles:

All patients → inpatient admission, IV antibiotics, and gynecology consultation.

Antibiotic therapy (hemodynamically stable, premenopausal, unruptured TOA <7 cm):

Success rate >70% with antibiotics alone.

Standard regimen: ceftriaxone + doxycycline + metronidazole.

Alternatives: cefoxitin, cefotetan, or ampicillin‑sulbactam + doxycycline.

Duration:

IV for 2–3 days → transition to oral once improved (afebrile, less tenderness, downtrending WBC/inflammatory markers).

Oral therapy continued for 14 days total.

Common oral regimens:

Metronidazole or clindamycin + doxycycline.

Levofloxacin or moxifloxacin + metronidazole.

Amoxicillin‑clavulanate.

Indications for operative drainage:

Abscess >7 cm.

Ruptured abscess.

Unstable vitals or sepsis.

No improvement after 72 hours of IV antibiotics.

Postmenopausal women (higher malignancy risk).

Surgical options:

Historically: TAH + BSO (open surgery).

Increasingly: unilateral salpingo‑oophorectomy in select patients.

Stable, unruptured abscess: laparoscopic or image‑guided percutaneous drainage may be considered.

Postmenopausal: open surgery recommended to assess for malignancy/metastatic disease.

-

chronic pelvic pain

infertility

increased risk of ectopic pregnancies in the future due to adhesions and scar tissue

-

Can present without fever (~40%).

PID patient with worsening pain/mass → suspect TOA.

Rupture = sepsis risk → urgent resus + GYN consult.

CRP >49 mg/L strongly supports diagnosis.

Ultrasound first; CT adds sensitivity and rules out other causes.

Broad‑spectrum IV antibiotics + admission are standard; escalate to drainage/surgery if >7 cm, ruptured, unstable, or postmenopausal.

Summary

Ovarian emergencies may represent a minority of gynecologic presentations in the ED, but their impact can be significant. Torsion, cyst rupture, and tubo‑ovarian abscess each carry unique diagnostic challenges and require vigilance, timely imaging, and early gynecology involvement. Recognizing subtle presentations, maintaining a broad differential, and acting decisively can prevent morbidity, preserve fertility, and in some cases save lives. By sharpening awareness of these high‑stakes pathologies, emergency physicians can better navigate the complexity of acute pelvic pain and ensure patients receive the urgent care they need.

POST BY Dalton Bannister, MD

Dr. Bannister is a PGY-1 resident at the University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine Residency.

EDITING BY ANITA GOEL, MD

Dr. Goel is an Associate Professor at the University of Cincinnati, a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2018, and an assistant editor of Taming the SRU.

References

Agur, A. M. R., Dalley, A. F., II, & Moore, K. L. (2019). Moore's essential clinical anatomy, 6e. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, a Wolters Kluwer business

Gibson E, Mahdy H. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Ovary. [Updated 2023 Jul 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545187/ Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):online

Heniff M, & Fleming H.B. (2020). Abdominal and pelvic pain in the nonpregnant female. Tintinalli J.E., & Ma O, & Yealy D.M., & Meckler G.D., & Stapczynski J, & Cline D.M., & Thomas S.H.(Eds.), Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 9e. McGraw-Hill Education. https://accessmedicine-mhmedical-com.uc.idm.oclc.org/content.aspx?bookid=2353§ionid=219643361

Mobeen S, Apostol R. Ovarian Cyst. [Updated 2023 Jun 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560541/ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology (2016). Practice Bulletin No. 174: Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses. Obstetrics and gynecology, 128(5), e210–e226. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768

Abduljabbar, H. S., Bukhari, Y. A., Al Hachim, E. G., Alshour, G. S., Amer, A. A., Shaikhoon, M. M., & Khojah, M. I. (2015). Review of 244 cases of ovarian cysts. Saudi medical journal, 36(7), 834–838. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2015.7.11690

Saber M, Ruptured ovarian hemorrhagic cyst. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-89358

Anan R, Ruptured hemorrhagic ovarian cyst. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-86342

Baron SL, Mathai JK. Ovarian Torsion. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560675/

Bridwell, R. E., Koyfman, A., & Long, B. (2022). High risk and low prevalence diseases: Ovarian torsion. The American journal of emergency medicine, 56, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.03.046

Houry, D., & Abbott, J. T. (2001). Ovarian torsion: a fifteen-year review. Annals of emergency medicine, 38(2), 156–159. https://doi.org/10.1067/mem.2001.114303

Huchon, C., & Fauconnier, A. (2010). Adnexal torsion: a literature review. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology, 150(1), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.006

Garde, I., Paredes, C., Ventura, L., Pascual, M.A., Ajossa, S., Guerriero, S., Vara, J., Linares, M. and Alcázar, J.L. (2023), Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound signs for detecting adnexal torsion: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol, 61: 310-324. https://doi.org/10.1002/uog.24976

Bani doumi H, Ovarian torsion. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-181584

Patel M, Ovarian torsion. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-85486

Osborne N. G. (1986). Tubo-ovarian abscess: pathogenesis and management. Journal of the National Medical Association, 78(10), 937–951.

Bridwell, R. E., Koyfman, A., & Long, B. (2022). High risk and low prevalence diseases: Tubo-ovarian abscess. The American journal of emergency medicine, 57, 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2022.04.026

Ilmer, M., Bergauer, F., Friese, K., Mylonas, I., Genital Tuberculosis as the Cause of Tuboovarian Abscess in an Immunosuppressed Patient, Infectious Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2009, 745060, 4 pages, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1155/2009/745060

Kinay, T., Akay, A., Aksoy, M., Celik Balkan, F., & Engin Ustun, Y. (2024). Risk factors for antibiotic therapy failure in women with tubo-ovarian abscess: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research, 50(3), 298–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/jog.15870

Landers, D. V., & Sweet, R. L. (1983). Tubo-ovarian abscess: contemporary approach to management. Reviews of infectious diseases, 5(5), 876–884. https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/5.5.876

Demirtas, O., Akman, L., Demirtas, G. S., Hursitoglu, B. S., & Yilmaz, H. (2013). The role of the serum inflammatory markers for predicting the tubo-ovarian abscess in acute pelvic inflammatory disease: a single-center 5-year experience. Archives of gynecology and obstetrics, 287(3), 519–523. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-012-2600-3

Ribak, R., Schonman, R., Sharvit, M., Schreiber, H., Raviv, O., & Klein, Z. (2020). Can the Need for Invasive Intervention in Tubo-ovarian Abscess Be Predicted? The Implication of C-reactive Protein Measurements. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology, 27(2), 541–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmig.2019.04.027

Gil, Y., Capmas, P., & Tulandi, T. (2020). Tubo-ovarian abscess in postmenopausal women: A systematic review. Journal of gynecology obstetrics and human reproduction, 49(9), 101789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101789

Botz B, Tubo-ovarian abscess. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-83123

Hacking C, Tubo-ovarian abscess. Case study, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 19 Nov 2025) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-34719