Intern Diagnostics: Approach to the Limping Child

/A child’s inability to walk normally is a common cause of emergency department visits. While the differential diagnosis of the limping child is extensive and the majority of etiologies are due to mild or self-limiting events, sometimes a limp is a sign of severe or life-threatening conditions that require emergent intervention. The following article expands on key information and diagnoses imperative for emergency physicians to consider in their initial evaluation and treatment of children presenting with gait abnormalities.

Normal Gait and Developmental Milestones

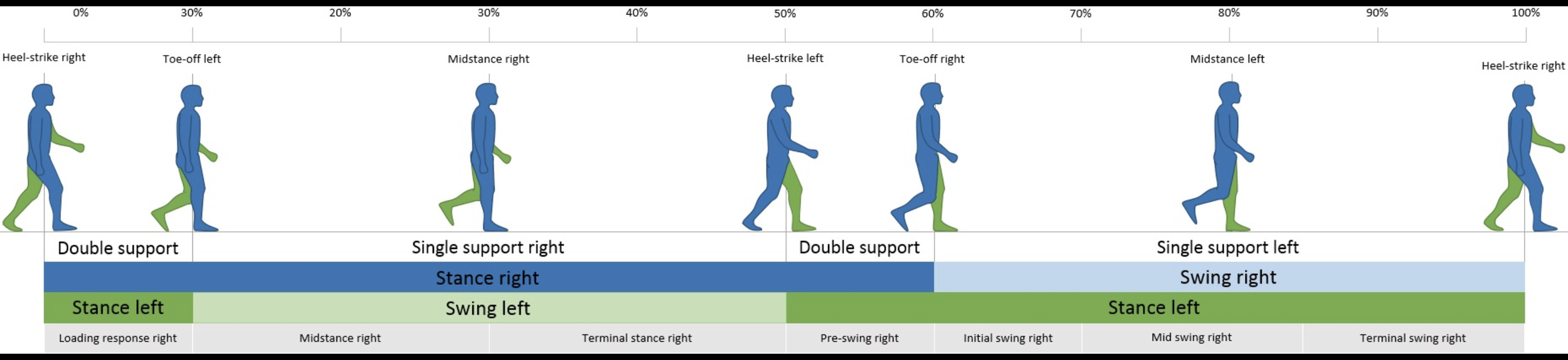

To understand gait variation, the emergency physician must first understand the normal gait pattern in children. Gait is divided into two main cycles- stance and swing phase. The stance phase is when the limb supports the weight of the body while the limb is in contact with the ground (1,2). It begins with heel strike and ends at toe-off of the same foot, and makes up about 60% of the gait cycle, whereas the swing phase begins with toe-off and ends with heel contact of the same foot and occupies about 40% of each cycle.

The timing of when a child can walk varies; however, usually children begin walking between 12-16 months of age (3). Toddlers usually take short, asymmetric steps with a wide base of support and occasional foot slapping as they increase speed (2). Falls are common in this age group due to poor balance, nonreciprocal arm and leg motion, and overall immature motor planning. Single-limb stance and gait stabilization, which are indicators of progression to mature gait, typically begin around 3-5 years of age (2,4). This is also the age that children are starting to be able to walk up and down steps appropriately with alternating feet. Mature gait resembling the gait of an adult is typically reached by 7 years of age.

What is an Abnormal Gait?

Abnormal gait can be described in one of two ways: antalgic and non-antalgic.

Antalgic gait is a pattern in which the stance phase is shortened to compensate for and avoid pain in the affected hip, knee, or ankle (2). An antalgic gait may also be translated into complete refusal to walk (1,5). Antalgic gait may also result in circumduction of the hips, which allows for foot clearance from the floor without significant motion of their painful joint (2).

Frequent causes of antalgic gait include bony fracture or stress fracture, joint swelling (septic arthritis, reactive arthritis, transient synovitis), or soft tissue injury from trauma. However, children may also present with an antalgic gait when they are being cautious from pain in another area of the body (i.e., if they have back pathology such as meningitis, spinal cord tumors, nerve radiculopathy, muscle spams in back, acute abdomen), so a full review of systems is very important to better localize the area of pain.

Non-antalgic gait refers to an abnormal gait pattern without pain as the presenting feature. Non-antalgic gait patterns are usually caused by underlying neurologic conditions or more chronic musculoskeletal conditions, and frequently do not require a diagnosis in the emergency department. Common examples include (1):

Steppage gait: patient excessive lifts leg off ground due to foot drop (neurologic cause)

Ataxic gait: patient with wide based unsteady gait due to poor coordination (central neurologic cause, usually either cerebellum or dorsal spinal column sensory issue)

Trendelenburg gait: patient shifts body weight over affected hip during stance phase to reduce force exerted on weak abductors (2). Hip abductor / gluteus muscle weakness causes the pelvis to drop on the unaffected side when standing on the affected leg. This may be caused specifically by nerve damage causing chronic muscle atrophy.

Trendelenburg and Antalgic gaits are distinguishable in the stance phase. The Trendelenburg stance phase is normal and not shortened because the patient is not avoiding pain (2).

Waddling gait: patient sways from side to side in a “duck-like” waddle due to weakness in BOTH gluteus medius muscles and subsequent pelvis instability (most commonly due to muscular dystrophy)

Equinus gait, otherwise known as “toe walking”: caused by musculoskeletal issues such as limb-length discrepancy, cerebral palsy, tight Achilles tendon (heel cord), calcaneal fracture, foreign body in foot, club foot

Vaulting gait: also toe walking, but only on the unaffected side – specifically patient will toe walk on the unaffected side to artificially lengthen that leg and better clear the affected leg during the swing stance (musculoskeletal cause such as leg length discrepancy, spasticity or contracture of knee or ankle on one side)

Important history questions to ask in the emergency department

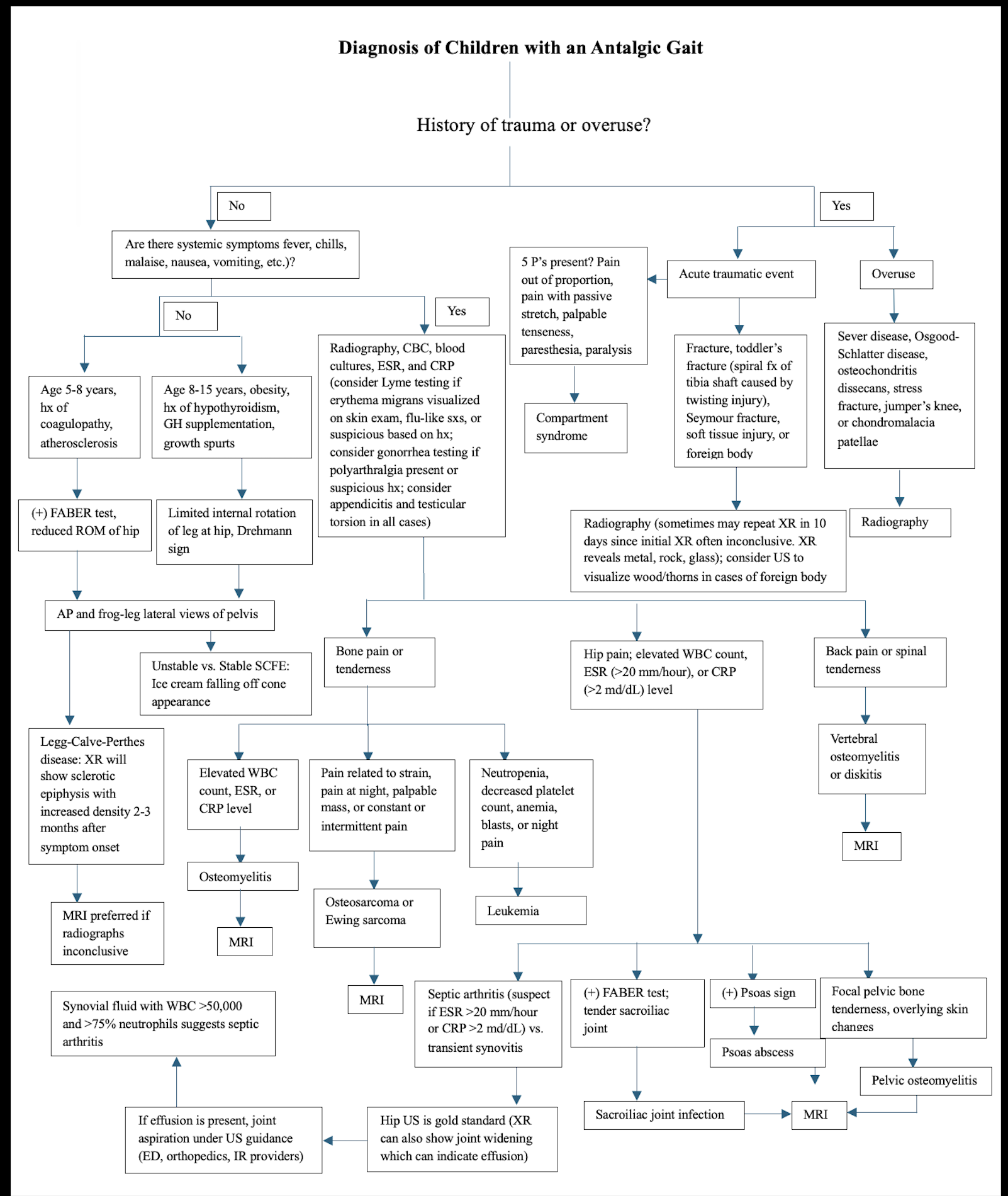

A thorough history and review of systems is of paramount importance in evaluating the pediatric limp. Some specific barriers to consider in the pediatric clinical setting include pre-verbal children and young children coming from environments where parents or caregivers are not present, resulting in gaps in observation of the child. Below is a great reference flowchart for diagnosing pediatric limp in the ER, with a focus on history questions leading to the correct type of work up to pursue.

History of Present Illness

The first key historical question to ask is whether the limp is painful or painless. If it is painful, ask about suspected source(s) of pain, history of trauma/sports activities, as well as the onset, duration, quality, and severity of pain. Intermittent pain at rest may raise your suspicion for a malignant bone tumor. Keep in mind that hip pain may oftentimes present as referred knee pain, and that back pain can also cause a limp. Ask whether the child can bear weight and if the parents/caregivers have noticed any pattern to their gait disturbance. In addition, be sure to ask about a history of recent trauma or sports activities, recent illness/infection (viral, MRSA+), tick/insect bites, or travel outside of the United States.

Review of Systems

In your review of systems, ask about fevers, chills, night sweats, back pain, rashes, weight gain/loss, loss of appetite, anorexia, or other sick symptoms. If non-accidental trauma/sexual abuse is suspected, interview the child and parents separately. Be sure to ask about gynecologic and urologic symptoms in these cases (3).

Physical examination of the limping child

First off, don’t forget to undress the child! Children are not always the best historians, especially when younger, and often you may miss important physical exam findings if you do not fully undress the patient. Additionally, having shoes on can often mask certain gait abnormalities, so make sure the child is barefoot before performing any gait testing.

Skin examination: Observe the skin fully for any cutaneous findings, such as café-au-lait spots, hairy patches, sacral dimples, rashes, tick bites, lesions, or bruises. Some of these may signal systemic causes of gait abnormalities that require a more rigorous work-up.

Standing examination: Examine the spine carefully. Assess range of motion with forward flexion, hyperextension, lateral flexion, and rotation. Check for obvious scoliosis of asymmetry, pain to palpation over spinous processes or paraspinal muscles, and step-offs or deformities.

If clinically indicated, have the child perform a Trendelenburg test, where the child stands on the affected leg with the knee flexed and hip extended for 20 seconds. This will fatigue the hip flexors which often mask a mild deficiency of the gluteus medius. A positive test often indicates a congenital hip dislocation / subluxation.

You may also have them perform the Gower test, where the child sits on the floor, then rise quickly. If they use their hands to push up and substitute for weak hip extensor muscles, muscular dystrophy is possible and requires a specialist consultation.

Tabletop Examination (Sitting and Supine): The tabletop examination begins with a gross examination with the patient sitting on the bed. Be sure to look for asymmetry, deformity, erythema, rashes, and swelling. Look on the plantar surfaces of the bilateral feet for puncture wounds or foreign bodies in walkers, and on the anterior knees in crawlers.

Have the patient lie supine on the bed. If there is a painful limb, be sure to assess the normal limb first. Examine the pelvis for skin changes and tenderness. Tenderness at the anterior superior and inferior iliac spines may be concerning for an avulsion fracture of the sartorius or of the direct head of the rectus (2).

Observe the resting position of the limbs. Children with septic arthritis of the hip will hold the hip flexed and externally rotated. Next, palpate the lower extremities and find the point of maximal tenderness on the affected leg after thoroughly examining the unaffected leg. Examine every joint of the lower extremity and take each one through its range of motion, noting pain, contractures, or muscle spasticity. Conclude your lower limb examination with a thorough neurovascular assessment.

other Special Physical Exam Maneuvers

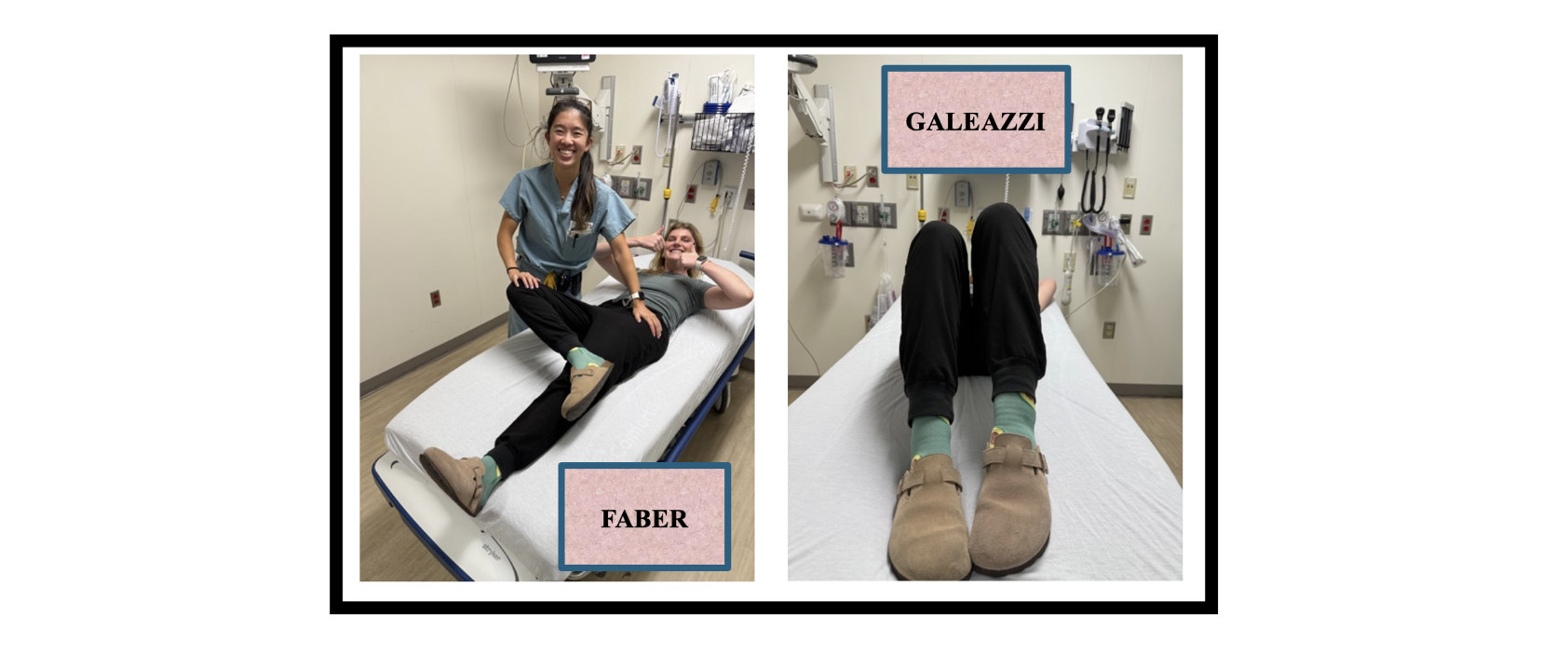

The FABER/Patrick test is used to assess for potential problems in the hip joint, sacroiliac joint, and surrounding muscles. Instructions: bend one knee at 90 degrees while keeping contralateral leg straight. Place the hip in flexion, abduction, and external rotation. Stabilize the opposite hip with one hand. Use slight pressure to stress the joint and determine if there is pain present.

The Galeazzi sign is used to assess for leg-length discrepancy that could indicate developmental dysplasia of the hip, femoral or tibia shortening, or a hip dislocation. Instructions: Place the child in a supine position with their hips and knees flexed. A positive test reveals that the knee on affected side is lower than the normal side

Differential Diagnosis Frameworks and Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic testing choices are dependent on the differential diagnosis based on history and physical exam findings. Three different diagnostic approaches to the pediatric limp may provide a more manageable mental framework for the emergency physician’s cognitive load:

Simple Framework for “Can’t Miss” Diagnoses - a method where physicians can use broad categories for consideration in their Ddx - trauma, infection, inflammatory, neoplasm.

Traumatic / Orthopedic Injuries - closed or open fractures, compartment syndrome, non-accidental trauma, slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE)

Infectious - septic arthritis, transient synovitis, osteomyelitis, deep soft tissue infections

Inflammatory - lyme disease, juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, other rheumatologic disease

Neoplasm - primary bone tumor (ewing, sarcoma, osteosarcoma), blood cell tumor (leukemia, lymphoma), soft tissue sarcoma

Aged-based Differential Diagnosis - a method where physicians use age ranges to consider various disease etiologies, noting that several diagnoses cross over between categories.

Toddler aged 3 and under: developmental dysplasia of the hip, congenital limb deficiencies, neuromuscular abnormalities, toddler fracture, septic arthritis, transient synovitis, reactive arthritis, osteomyelitis, foreign object in the knee or foot

Child age 3-10: legg-calve-perthes disease, stress fracture, tumor, osteochondrosis, Kohler disease, osteochondrosis, osgood-schlatter disease, transient synovitis, osteomyelitis, leg-length discrepancy

Adolescent / teenage age 10+: slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE), legg-calve-perthes disease, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JRA), overuse syndromes (osgood-schlatter and sever disease), osteochondrosis, tumors, osteochondritis dissecans, stress fractures, discoid meniscus

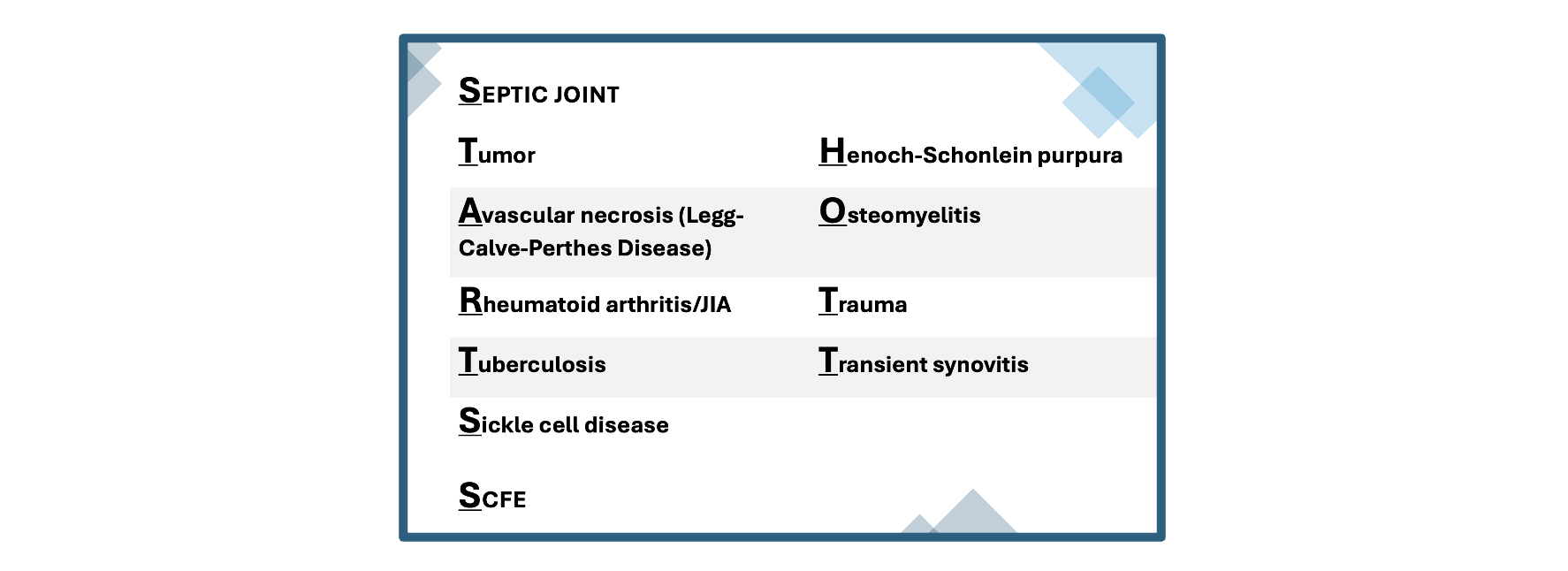

“STARTSS HOTT” - a mneumonic to remember the most common and can’t miss diagnoses for the ER physician to consider in their Ddx

work up in the emergency department

Lab work:

Lab work is often not indicated. However, if the clinician has concern for infectious, inflammatory, or oncologic processes, obtain a complete blood count (CBC) with differential count, C-reactive protein (CRP) level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and blood cultures (especially in febrile neonates). If there is concern for Lyme disease based on history and physical, consider obtaining Lyme antibodies.

Chronic inflammatory states, such as in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA / JRA), may result in elevated ESR, whereas the presence of blasts on CBC with differential count may suggest leukemia. If surgical intervention is indicated, emergency physicians may obtain CBC with differential count, basic metabolic panel, coagulation studies, and type and screen for pre-surgical purposes.

Imaging:

As a general rule of thumb, plain radiographs are typically warranted for most patients with focal areas of pain to rule out a fracture. Plain radiographs are efficient, available 24/7, inexpensive, and sensitive and specific for a wide variety of disorders. While they still expose the child to radiation, the amount of exposure is less than in secondary imaging modalities, and the benefits often outweigh the risks of obtaining plain films. X-rays may also reveal other abnormalities, such as signs of infection (i.e., periosteal reaction), neoplasm, developmental dysplasia of the hip, and slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE). If there is a high degree of suspicion for overuse injuries, such as Osgood-Schlatter disease, Sever disease, or sprains, radiographs are typically not of use in these scenarios and are not recommended (2,8). If there is concern for SCFE, obtain frog-leg lateral radiographs in addition to anteroposterior pelvis plain films.

Secondary imaging studies available in the emergency department setting include ultrasonography and CT scans. Ultrasonography is most utilized when there is a high clinical suspicion for septic arthritis of the hip. In these cases, the ultrasonographer looks for effusion and may complete ultrasound-guided hip joint aspiration via this modality. Furthermore, ultrasound may be used to identify deep soft-tissue abscesses, foreign bodies not seen on radiographs (i.e., splinters, glass, plastic) (2,8).

In cases of negative radiographs, MRI is another powerful secondary imaging modality that may be most useful for evaluating for osteomyelitis, benign/malignant neoplasms of soft tissue and bone, and for avascular necrosis of the femoral head due to sickle cell disease, Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, or other causes. MRI is both sensitive and specific. It can discern between small abscesses associated with septic arthritis and osteomyelitis.

CT scanning is often a last resort in pediatric imaging, due to high radiation exposure. It may be used to evaluate for occult bone fractures and benign lesions. CT scans may be most helpful in pre-surgical planning in conjunction with orthopedic specialist recommendations. Some benign lesions found on CT scans include simple bone cysts, osteoid osteomas, and nonossifying fibromas (2).

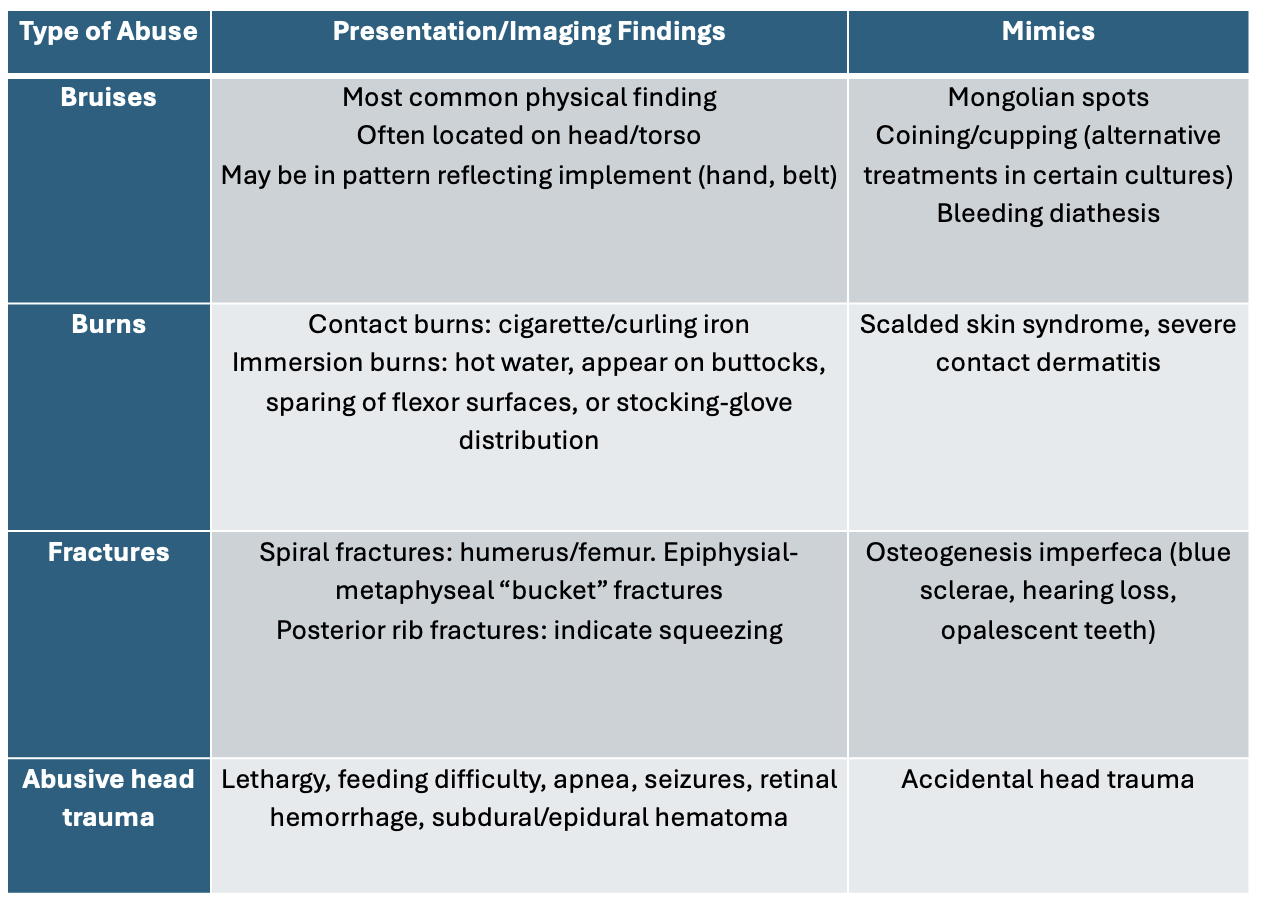

Special Considerations in Pediatrics: Is It Abuse?

While limping in a child may be caused by a myriad of musculoskeletal, rheumatologic, immunologic, infectious, and hematologic etiologies, the emergency physician must also have a very low threshold to suspect non-accidental trauma (NAT). Non-accidental trauma may include physical, sexual, and psychological maltreatment of children.

Risk Factors

There are certain pediatric patient populations more vulnerable to child abuse. Specific risk factors include parents with a history of alcohol or drug use disorder, children with complex medical problems, infants with colic (excessive crying for >3 hours per day for >3 days per week), and repeated hospitalizations of the child.

History and Physical Exam Findings

Stop and consider child abuse if the parents’ story is inconsistent with the child’s injury pattern or child’s developmental age (9). For example, stating that a 2-month-old “rolled off the couch” and sustained their presenting injuries is suspicious, as 2-month-olds cannot roll yet. Be weary if the parents’ story continually changes or is very vague. When conducting your history and physical exam, make note of bruising on fleshy areas, distinct patterns of bruises (indicative of object used), bruises of different ages and color, and well-circumscribed burns. If there are any concerning signs of child abuse, make sure to document the appearance of injuries thoroughly by uploading photos to the electronic medical record and describing your findings in your documentation (location, color, size, shape).

In addition, infants who present with apnea, seizures, feeding intolerance, excessive irritability, somnolence, and failure to thrive are “red flag” signs that should concern the emergency physician for child abuse. In older children, poor hygiene and behavioral abnormalities are common manifestations of non-accidental trauma.

In all clinical cases concerning for non-accidental trauma/child abuse, involve social work and notify Child Protective Services immediately.

Summary

In conclusion, pediatric limp accounts for approximately 5% of pediatric emergency department visits (2,8). The differential diagnosis of pediatric limp is extensive; however, there are a limited number of diagnoses that require emergent intervention. Treatment and ultimate disposition of the pediatric limp depend on its etiology. For example, if life and limb threats have been excluded by thorough history and physical, lab workup, and imaging, patients may be referred for close outpatient pediatric orthopedic or pediatric neurology follow-up for further workup of gait disturbances based on the suspected etiology. If the diagnosis is unclear, the patient’s clinical presentation is concerning for progressively worsening symptoms, or non-accidental trauma is suspected, the patient should be admitted for further workup and protection from assailants. Of note, a patient’s ultimate disposition may also depend on consultant recommendations. In emergency cases such as unstable SCFE, compartment syndrome, open fractures, septic arthritis, aggressive neoplasm, or other neurovascular compromise, patients may require rapid transport to the operating room.

pOST BY Lauren huang, MD

Dr. Huang is a PGY-1 in Emergency Medicine residency at the University of Cincinnati.

EDITING BY ANITA GOEL, MD

Dr. Goel is an Associate Professor at the University of Cincinnati, a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2018, and an assistant editor of Taming the SRU.

References

Sawyer JR, Kapoor M. The limping child: a systematic approach to diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):215-224.

Herman MJ, Martinek M. The limping child. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36(5):184-195; quiz 196-197. doi:10.1542/pir.36-5-184

Flynn JM, Widmann RF. The limping child: evaluation and diagnosis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9(2):89-98. doi:10.5435/00124635-200103000-00003

Sutherland D. The development of mature gait. Gait Posture. 1997;6(2):163-170. doi:10.1016/S0966-6362(97)00029-5

What Is My Gait and Do I Have a Gait Abnormality? Cleveland Clinic. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21092-gait-disorders

Storer SK, Skaggs DL. Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(8):1310-1316.

Valisena S, De Marco G, Vazquez O, et al. The Kocher–Caird Criteria for Pediatric Septic Arthritis of the Hip: Time for a Change in the Kingella Era? Microorganisms. 2024;12(3):550. doi:10.3390/microorganisms12030550

Truong T, Chang D, Friedman S. Limping Child. Pediatr Rev. 2024;45(8):476-478. doi:10.1542/pir.2023-006052

Le T, Bhushan V, Deol M, Reyes G. First Aid for the USMLE Step 2 CK, Tenth Edition: Le, Tao, Bhushan, Vikas: 9781260440294: Amazon.com: Books. Accessed August 11, 2025. https://www.amazon.com/First-Aid-USMLE-Step-Tenth/dp/126044029X

EM:RAP CorePendium. EM:RAP CorePendium. Accessed August 28, 2025. https://www.emrap.org/corependium/chapter/rec2IN7kWX76sp4Qn/Approach-to-the-Limping-Child.