Joint Fluid Analysis in the ED

/Introduction

Piece of cake, you think to yourself as you review the chart of your next patient. A 60 year old male with a history of osteoarthritis with knee pain. No diagnostic dilemma here, right? You find that the patient is afebrile and well appearing. They have a three-day history of progressive knee pain which acutely worsened today, and on exam you find a warm and erythematous right knee with an appreciable effusion and limited ROM. Is this their normal arthritis? Could this be a septic joint? Do they have Lyme disease? You perform the arthrocentesis, but how do you interpret the synovial fluid?

Looking at the fluid

There are three characteristics of synovial fluid that you can analyze clinically right away: the color of the fluid, the clarity of the fluid, and the viscosity of the fluid. None of these findings may be highly sensitive or specific to your diagnosis of septic arthritis by themselves, but taken together with the other labs and your history and physical exam, they may contribute to your overall clinical acumen.

Is this yellow/greenish and opaque fluid more likely to be infectious? Are these subjective findings very sensitive or specific? The answer to that is maybe. One study based out of France found purulent synovial fluid appearance to have an odds ratio of 8.4 that was significant for septic arthritis (2). This intuitively makes sense, just as finding purulent versus clear CSF makes us more likely to think true bacterial meningitis. Normal synovial fluid is clear in color, transparent in clarity, and highly viscous. Therefore, fluid that is yellow/green, opaque, and very thin is more likely to represent a septic joint.

Lab Studies

The following is a list of joint fluid studies that you should order for every arthrocentesis you perform:

- The WBC count: this is the total number of leukocytes present in 1 cubic millimeter (#WBCs/mm3)

- The WBC differential: the most important part of which is the PMN % - the percentage of the total WBC count that are polymorphonuclear leukocytes

- Crystals: to evaluate for crystal induced arthropathies, most commonly monosodium urate crystals in gout and calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate in pseudogout

- Gram stain: An easily performed test that can provide quick information concerning the diagnosis and choosing therapy (Gram-positive versus Gram-negative coverage) (1)

- Culture: The gold standard in the diagnosis of septic arthritis

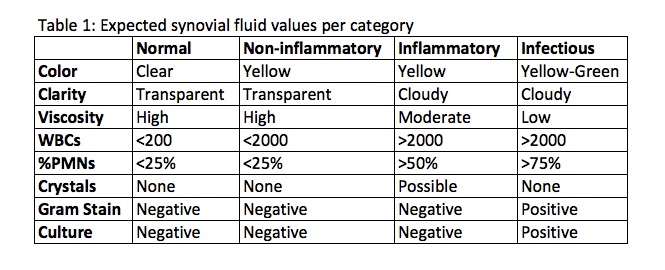

Based on these results, synovial fluid can be categorized as normal, non-inflammatory, inflammatory, or infectious. So let’s look further into analysis of these results.

Interpreting the Results

- WBC count: Contrary to the dogmatic approach, there is no arbitrary cut-off at 50,000 WBCS/mm3 at which a septic joint is diagnosed. In fact, in a meta-analysis published by Carpenter et al in 2011 in Academic Emergency Medicine found that this level had a sensitivity of only 56% (3). Based on several studies, the WBC count is >50,000/mm3 in only 50-70% of patients with septic arthritis (4). What we do know is that the higher the WBC, the more likely that septic arthritis is present (5). A 2007 systematic review found that as the synovial WBC count increased from 25,000/mm3 to over 50,000/mm3 or to over 100,000/mm3, the positive likelihood ratio (+LR) increased from 2.9 to 7.7 and to 28, respectively (6). Of note, there are studies that also show evidence of WBC >50,000/mm3 and even up to around 150,000/mm3 caused by gout alone.

- WBC Diff: The most important part of the differential for emergency physicians, when investigating for septic arthritis, is the % PMNs. Four studies have shown that polymorphonuclear cells of at least 90% are associated with septic arthritis (6). When this percentage is at least 90%, the likelihood of septic arthritis is increased (+LR, 3.4); and for percentages less than 90%, the likelihood decreased (+LR, 0.34) (6). Other findings that may arise with the WBC differential is an eosinophilia, which may suggest a parasitic infection, allergy, neoplasm, or Lyme disease (7,8).

- Crystal search: The patient with an acutely painful joint that you tap may or may not have a history of gout or pseudogout, but either way the synovial fluid analysis will investigate for crystals. Monosodium urate crystals are diagnostic for gout, and will appear needle shaped and have negative birefringence (blue color) (9). Calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystals are diagnostic for pseudogout, and will appear rhomboid in shape with positive birefringence (yellow color) (9). Does the presence of crystals rule out septic arthritis? No, it doesn’t. There are several case reports as well as one retrospective review of 30 hospitalized cases that all had positive bacterial cultures and monosodium urate crystals in the affected joint (10).

- Gram stain: The sensitivity and specificity of synovial fluid gram staining is not precisely known. Based on various studies, gram stains are positive in approximately 71% of gram-positive causes, 40-50% of gram-negative causes, and less than 25% of cases of gonococcal septic arthritis (11).

- Culture: This is the gold standard in diagnosing septic arthritis. Routine bacterial culture will be very sensitive and specific at growing out staph, strep, and gram-negative bacteria. However, the culture for Neisseria gonorrhoeae is positive in less than 50% of synovial fluids, which may be the result of the difficulty in growing this organism in vitro (11). If you suspect this organism to be the cause, it is recommended that you send cultures to be submitted on Thayer-Martin media of synovial fluid, skin lesions, urethral swab, cervical swab, and rectal swab.

Putting it all together

- For primarily inflammatory findings, keep in mind both crystal-induced arthropathies as well as other potential autoimmune causes like RA or SLE

- Septic arthritis is NOT defined by >50,000/mm3 WBCs in the synovial fluid; use your clinical gestalt and the entire picture to define your diagnosis

- Crystals in the synovial fluid does not preclude the joint from being septic

- If a septic arthritis diagnosis cannot be reliably excluded after clinical evaluation, including arthrocentesis, admit the patient for IV antibiotics and pain control until culture results are available (8)

- Based on clinical suspicion, additional testing may be pursued including serum Borrelia burgdorferi DNA PCR and special staining and culturing for TB or fungal organisms (1)

Post by Shaun Harty, MD

Peer Review and Editing by Ryan LaFollette, MD

References

- Sholter, D.E. and Russell, A.S. Synovial fluid analysis, Uptodate, last updated Feb 4, 2016

- Couderc, M., Pereira, B., Mathieu, S., Schmidt, J., Lesens, O., Bonnet, R., Soubrier, M. and Dubost, J.-J. (2015) ‘Predictive value of the usual clinical signs and laboratory tests in the diagnosis of septic arthritis’, CJEM, 17(4), pp. 403–410. doi: 10.1017/cem.2014.56.

- Carpenter, C. R., Schuur, J. D., Everett, W. W. and Pines, J. M. (2011), Evidence-based Diagnostics: Adult Septic Arthritis. Academic Emergency Medicine, 18: 781–796. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2011.01121.x

- Brannan, S.R. and Jerrard, D.A. (2006), Synovial fluid analysis. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2006 Apr;30(3):331-9

- Sternbach, G.L. and Baker, F.J. 2nd. (1976), The emergency joint: arthrocentesis and synovial fluid analysis. JACEP. 1976 Oct;5(10):787-92

- Margaretten, M.E., Kohlwes, J., Moore, D., and Bent, S. (2007), Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA 2007 Apr 4;297(13):1478-88

- Kay J, Eichenfield AH, Athreya BH, et al. Synovial fluid eosinophilia in Lyme disease. Arthritis Rheum 1988; 31:1384.

- Dougados M. Synovial fluid cell analysis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 1996; 10:519.

- Stapczynski, J. Stephan., and Judith E. Tintinalli. Tintinalli's Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education, n.d. Print.

- Yu, K.H., Luo, S.F., Liou, L.B., Wu, Y.J., Tsai, W.P., Chen, J.Y., and Ho, H.H. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003 Sep;42(9):1062-6. Epub 2003 Apr 16.

- Garcia-De La Torre, I. and Nava-Zavala, A. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009 Feb;35(1):63-73. Doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.03.001.