Grand Rounds Recap 1.31.18

/ULTRASOUND UPDATES: DVT STUDIES WITH DR. STOLZ

Terminology

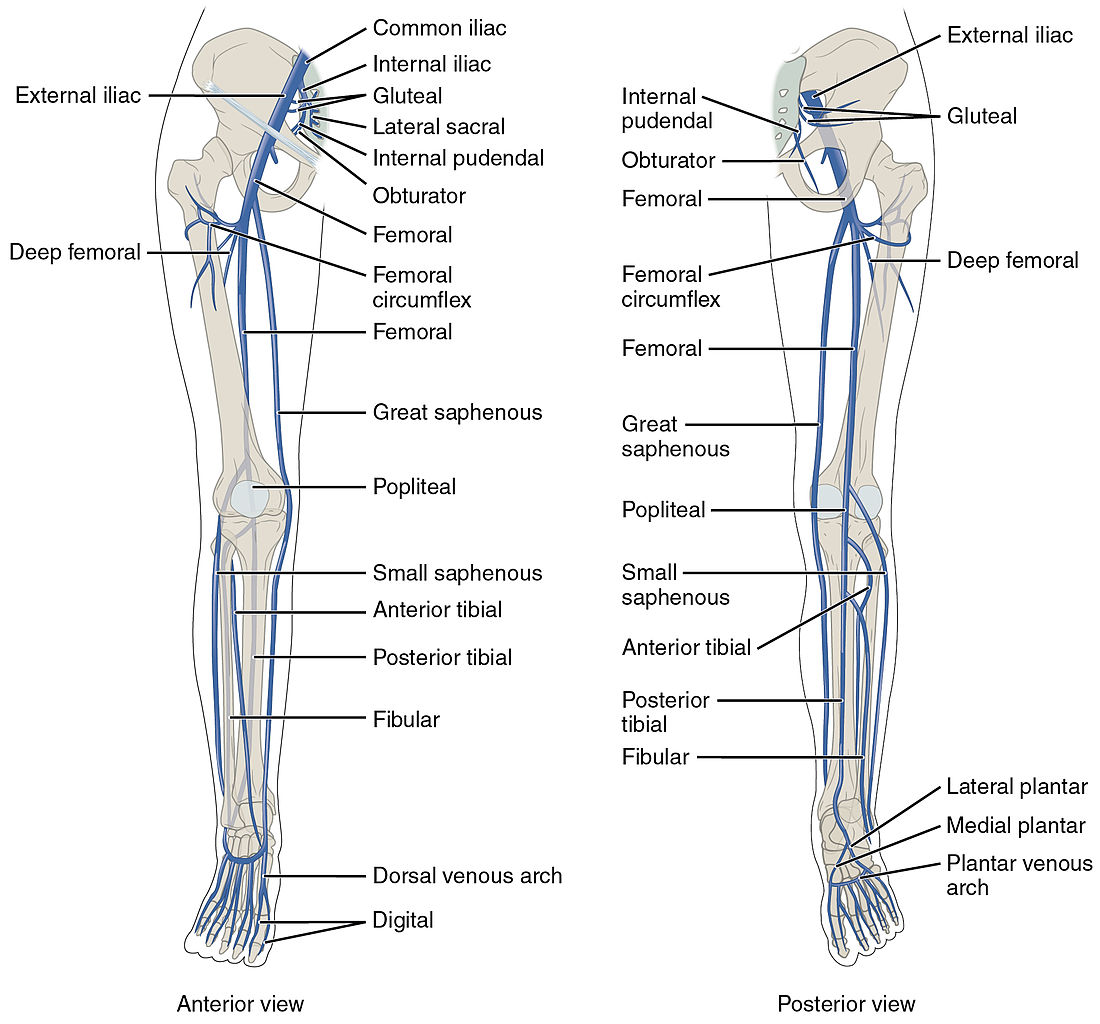

- Proximal: any femoral vein and the popliteal vein

- Distal: anything distal to the popliteal, including the anterior and posterior tibial veins

- Superficial vein thrombosis: great saphenous and small saphenous veins

The Two-Point Compression Ultrasound

- There are multiple types of scans, including scans of the whole leg, two-point compression studies, and duplex studies.

- The more comprehensive studies take up to 45 minutes to complete; Emergency Physicians have thus gravitated towards the more efficient two-point compression studies.

- While some facilities have robust DVT outpatient protocols, many hospitals do not have these policies in place. Additionally, a formal study can also take significant time, which is detrimental to throughput, or a patient may be too sick to travel out of the department.

- One study found that it is 125 minutes faster to get a bedside ultrasound done by an Emergency Physician rather than send a patient for a comprehensive scan.

- Two-point compression study looks at the common femoral vein and the popliteal vein. The study has a >96% sensitivity and specificity when used by EPs.

- There is some data, however, that you will miss isolated femoral or deep femoral clots with a two-point exam, although this rate is about 6% in the ED patient population (Adhikari, 2015)

- As such, the modified two-point exam was created, which looks at the femoral vein, the common and deep femoral veins, and the popliteal vein.

Walking Through a Study...

- Choose the linear probe to start with. If habitus is making visualization difficult, consider a curvilinear probe.

- Start at the common femoral vein at the inguinal ligament; you should see the common femoral vein and artery as landmarks.

- Work your way down to the saphenofemoral junction; if there is a clot here, this counts as a DVT!

- The common femoral will then bifurcate into the deep femoral and femoral veins.

- Apply compression at all of the above sites and assess for compressibility. How do you know if you're compressing hard enough? If you see some mild compression of the artery, that's probably good enough!

- You can look for augmentation: squeeze the lower extremity, which causes sudden venous return and a rapid increase in blood flow. An occlusive distal thrombus will decrease this response, although rarely diagnostic it can be useful comparing sides.

- You then attempt to look at the popliteal vein. This can be difficult based on the patient's ability to externally rotate or lift their leg. Hanging a patient's leg off the bed can also help make this part of the exam easier.

- The popliteal vein sits on top of the popliteal artery ("pop on top").

Pearls & Pitfalls

- The most common mistake EPs make in doing this study is not getting full visualization of the popliteal vein. It's easy to mistake the small saphenous vein or another superficial vessel for the popliteal.

- Another common pitfall is failure to fully compress the veins. If you're not sure if something is completely compressible, you can compare to the contralateral leg.

- If you try to compress in a long axis, you'll likely slide off the vein; compress only in the short axis.

- If you identify a clot, should you compress it? Will this embolize based on your compression? There are a couple of case reports of this occurring, but overall it's quite rare. If you see a free floating thrombus, however, it's probably best to leave this alone.

- Acute vs chronic thrombus? Usually an acute thrombus is more anechoic, smooth appearing with clean edges.

- Don't forget that you can use d-dimer to help risk stratify these patients.

- In the case of patients who are high risk OR have a positive d-dimer but go on to have a negative study, about 5% will go on to have a DVT discovered later. For these patients, they need follow-up with a repeat DVT study.

- In a patient with hemodynamic compromise where you are considering massive PE but the patient is either too unstable for CT scan, consider a bedside lower extremity ultrasound to help narrow your differential.

- What do we do with calf vein DVTs? This is still controversial, and there is no great data on whether these clots can go on to become PEs. A recent study in JAMA Surgery showed that the NNT was 16.9 to prevent PE or DVT within 30 days, but the NNH for clinically significant bleeding was 15! This is where a shared decision-making conversation with the patient can help.

EM-NEURO COMBINED CONFERENCE: ACUTE STROKE MANAGEMENT WITH DR STETTLER

Case 1

- Elderly male with a history of afib (on dabigatran) and DM who presents with sudden onset left-sided weakness that occurred while at work approximately an hour ago. Your exam reveals no antigravity on the left with a left-sided facial droop and significant neglect. A non-contrast head CT is unremarkable.

- You discover that his last dose of dabigatran was 27 hours ago. A CTA shows a right M2 occlusion.

- The MR CLEAN study: NEJM study from 2015 that looked at 500 patients with occlusions of the distal ICA, M1/M2 or A1/A2. It did not evaluate posterior circulation occlusion. 89% of these patients were treated with IV t-PA.

- The intervention was intra-arterial therapy. Modified Rankin Scales for the intervention group at 3 months were significantly better compared to the control groups.

- What should you do with giving t-PA to patients who are on the "novel" oral anticoagulants? This all comes down to history and the last dose of their medication.

Case 2

- Elderly female with a history of HTN, HLD who presents with right sided weakness and aphasia with a right facial droop upon waking up in the morning. She presents at 0830. She was last seen normal when she went to bed that night at 2200. A non-contrast head CT shows an evolving left-sided infarct.

- The DAWN trial: recently published trial that looked at 206 patients with distal ICA or M1 strokes with NIHSS greater than or equal to 10. These patients had a last known normal time of between six to 24 hours, and had a mismatch between core infarct and penumbra on MR or CT perfusion imaging. Those with a significant mismatch received thrombectomy.

- This study showed a profound difference in patients who received thrombectomy compared to the control group with regards to their Modified Rankin Scale. The study was stopped early due to positive effect.

- What is an ASPECTS score? It is ten point scale which attempts to quantify the degree of MCA infarct based on a non-contrast CT.

- Timing of lytics? IV t-PA is a hard stop at 270 minutes from last known normal. For intraarterial t-PA, in the anterior circulation, the cutoff is 6 hours. The posterior circulation timing cutoff may be more--up to 12 hours depending on what studies you read.

In general, your approach to suspected acute ischemic stroke--in conjunction with the stroke team-- should be:

- Last known normal less than 4.5 hours? If so, give IV t-PA and get a CTA. If the CTA is negative for a large vessel occlusion, the patient goes to the ICU. If they have a large-vessel occlusion, they should go to angio for iA t-PA and/or thrombectomy.

- If their last known normal is greater than 4.5 hours, IV t-PA is contraindicated. If they are between 4.5 hours and 6 hours, get a CTA and send the patient to angio if there is a large vessel occlusion.

- If they are greater than 6 hours out but less than 24 hours, get a CTA/CTP. If the CTA is positive for a large vessel occlusion with a core infarct/penumbra mismatch on CTP, send the patient to angio. If there is no significant mismatch, admit to the appropriate level of care.

QUARTERLY SIM WITH DRS CONTINENZA, FERNANDEZ, LAFOLLETTE, LOFTUS and HILL

Simulation -- House Fire

The patient is a 60-year-old male who was found down in a house fire. After a prolonged extraction time, the patient was found to be unresponsive and was intubated by paramedics with etomidate and succinylcholine. En route, EMS loses their peripheral access. Upon arrival he is hypotensive (70s/40s), hypoxic in the high 80s on an FiO2 of 100% and hypothermic.

On exam, he is found to have full-thickness circumferential burns around his chest as well as burns involving his extremities and face. Access is established via IO and labs are sent. Resuscitation is began with IV fluids. His labs were notable for a lactate of 22 and a carboxyhemoglobin level of 32. Given his profound hypotension and hypoxia, CyanoKit is given. His hypotension improves with this, but the patient has continued difficulty with oxygenation and compliance on the vent. Given this, an escharotomy was performed of the chest, which does improve his oxygenation and vent dynamics.

- Establishing IV access in burns patients can be difficult. Move early to an IO in the acute phase of treatment and stabilization.

- For refractory shock in patients from house fires or other industrial exposures, consider cyanide poisoning as an etiology. The classic patient with cyanide poisoning comes from an enclosed house or structure fire, and has hemodynamic instability with high lactate levels. CyanoKit administration can exact profound hemodynamic changes and has even been reported to aid in obtaining ROSC.

- Try to get your labs before giving CyanoKit, as the color of the infusion can affect many serum lab tests. However, this should not delay administration in the unstable or coding patient.

- For patients with circumferential burns with hemodynamic or vascular compromise, consider escharotomy. Remember that this is not a fasciotomy, and only go through the burned tissue. Electrocautery, if available, can help with bleeding of viable tissue below the eschar.

- Given his altered mental status and carboxyhemoglobin level, this patient needs hyperbarics. In dispositioning this patient from a smaller community hospital, look for a facility that has both hyperbaric medicine and a burn center.

- Don't forget standard burn care, including calculating a Parkland Formula for IVF resuscitation, antibiotics as indicated and tetanus.

Mock Oral Boards

Triple Case

Patient One: The patient is a middle aged female who is brought into the ED via EMS after an MVC. She had an obvious deformity of her left arm, which was splinted by EMS. On arrival she is generally well appearing with stable vitals. She is complaining of left arm pain and denies any other complaints. Exam reveals a closed deformity of the left forearm without any neurovascular compromise. X-rays reveal a fracture and dislocation consistent with a Galeazzi fracture . After the patient is consented, conscious sedation is performed and the wrist is reduced and splinted. She is discharged with ortho follow up.

Critical actions included: providing appropriate analgesia, obtaining consent and discussing risk/benefit with the patient for deep sedation, and putting a sugartong splint on a Galeazzi fracture with appropriate ortho follow up.

Patient Two : The patient is an elderly female with a history of HTN, HLD and DM who pushed her LifeAlert button after falling. She reports that her legs gave out from underneath her while she was getting out of bed, and she could not get up off the floor. EMS brings her to the ER. She denies hitting her head and states that other than some aching and weakness in her legs, she feels well. She is found to be in a-fib, which is a new diagnosis for her. On exam, she has absent palpable and dopplerable pulses on the left, and only dopplerable pulses on the right. She is started on a high-dose heparin drip for presumed ischemic limb, and vascular surgery is consulted.

Critical actions included: performing a full vascular exam, ordering CTA of the aorta with runoff into the extremities, ordering a high dose heparin drip, and consulting vascular.

Patient Three : The patient is a middle aged male with a history of CAD, HTN and HLD who presents to the ED with a headache. He reports the recent onset a few weeks ago of headaches that are intermittently responsive to ibuprofen. He reports today he woke up with a headache that was associated with nausea and chest pain as well. His physical exam is unremarkable. He does note that he has had someone working on his furnace recently. Due to his history of CAD, a cardiac workup is initiated which reveals a borderline elevated trop of 0.04 and an EKG with some subtle ST elevation but no evidence of STEMI. A bedside cardiac ultrasound does not reveal any evidence of effusion. A carboxyhemoglobin level is 22. He is placed on a non-rebreather at 15 lpm and is admitted to the hospital for carbon monoxide poisoning.

Critical actions included: considering CO poisoning and disposition appropriately based on CO levels and patient symptoms.

Case Two (eOrals)

The patient is a 58-year-old female with a history of HTN and HLD who presents to the ED for four hours of chest pressure and pain. She states that she was sitting at work when she developed a sharp pain radiating to her left shoulder. She is mildly hypertensive and is satting 93% on RA but otherwise has unremarkable vitals. EKG is notable for inappropriate ST elevation in II, III and aVF as well as V4-V6 with ST depression in the septal leads and a new LBBB. She is given full dose aspirin and interventional cardiology is contacted. As she has ongoing chest pain she is given morphine. She is loaded with clopidogrel and and given a heparin bolus and goes to the cath lab for further management of her STEMI.

Critical actions included: ordering an EKG, identifying a STEMI in the setting of a LBBB, giving ASA/heparin, and activating the cath lab.

ADULT INFECTIOUS DIARRHEA WITH DR LANE

- Definition of diarrhea: either 3 or more liquid or loose stools per day, or more frequently than is normal for the individual.

- Acute: symptoms less than 14 days; persistent: symptoms for 14-30 days; chronic: more than 30 days.

- There are 180 million cases of acute diarrhea each year; 48 million of these cases are food-borne.

- Viral causes are far more likely than bacterial etiologies of diarrhea, and norovirus alone represents 25% of all diarrheal illnesses in the United States.

- C. difficle is progressively more common, representing a more frequent etiology of acute diarrhea in the US.

- Historical factors that are useful include: the age of the patient, the presence of fever, and the presence of blood. Other historical factors, such as the presence of emesis, recent travel or the duration of the symptoms, can also be helpful but are not necessarily diagnostic.

- Physical exam should include examination for systemic illness, a focused abdominal exam, and a rectal exam if the patient is complaining of blood in their stool.

- Imaging is generally not helpful unless there is concern for a serious abdominal pathology such as perforated viscous, toxic megacolon or abscess. Labs can be helpful to assess the severity of the patient's dehydration, but a white blood cell count is neither sensitive nor specific with regards to bacterial versus viral etiology of acute diarrhea.

- Stool studies should be considered for: severe acute diarrhea (where the patient is systemically ill), grossly bloody stools, in the elderly or immunocompromised patient, in patients with risk factors for C diff colitis, or people with exposure to potential pathogens such as day care workers or food handlers.

- For mild to moderate non-bloody diarrhea, guidelines recommend oral hydration and loperamide. If the patient has a high fever or severe symptoms, they do recommend considering empiric treatment with azithromycin 1g once.

- For mild to moderate bloody diarrhea in a well appearing and afebrile patient, guidelines recommend a test-and-treat method for bacterial diarrhea, and withholding any treatment until a causative etiology is identified. If the patient has a high fever or severe symptoms, guidelines do recommend empiric treatment with azithromycin 1g once as well as stool testing. Patients with recent international travel should also be considered for antibiotic therapy.

- Diarrheal illnesses can precede other more serious conditions such as reactive arthritis, Guillain-Barre syndrome, and thoracic aortitis.

R4 CASE FOLLOW UP WITH DR SHAH

The patient is an approximately 30-year-old male who was found down and unresponsive and presents to a small community ER via EMS. Per their report, he was found down next to his bicycle. He was unhelmeted. He was given 4 mg of narcan without effect. On presentation he is unresponsive but does have stable vitals. His eyes are open, but he is not regarding the examiner nor participating with exam. He has some scalp and facial abrasions that appear superficial. His pupils are equal and reactive. He does have some abdominal bruising and abrasions on his extremities. On skin exam it is noted that he has old EKG stickers on him. Neurologically, he is a GCS of 3-1-2 with some questionable extensor posturing.

The patient was given narcan and versed for possible overdose versus non-convulsive status without improvement of his GCS. He was intubated for airway protection and then went to CT scan. Labs were notable for some mild dehydration and hemoconcentration, a lactate of 3.1 and CK of 1180. A tox workup was unremarkable. He was empirically covered for meningitis and transferred to the NSICU at a larger academic hospital.

There, repeat neurologic imaging was stable. An EEG showed some slowing but no evidence of seizure activity. He is then identified as a male with a history of TBI with residual pseudobulbar affect. On HD1, the patient woke up, self-extubated and gradually improved over the course of the day to his baseline mental status. He then states that he has been taking medication he buys on the internet from China for his pseudobulbar affect which turns out to be dextromethorphan (DXM). The patient is diagnosed with DXM overdose.

- DXM is, amongst other things, a NMDA antagonist, mu receptor agonist, 5-HT1 agonist, histamine H1 agonist.

- It is metabolized through the liver and has active metabolites, some of which interact with other medications.

- It is a drug of abuse and often seen in younger patients who take over the counter cough and cold medications for recreational purposes.

- The therapeutic dose is 0.3 mg/kg. There is a dose-dependent effect of the medication that starts with euphoria and increased energy (1.5-2.5 mg/kg) and progresses to visual hallucinations, dissociation and agitation (2.5-15 mg/kg). In very high doses (>15 mg/kg in a single dose), complete dissociation, seizures, coma and death can occur.

- Treatment for overdose is primarily supportive care, but due to the mu agonist activity, narcan is also recommended. In very acute overdoses, activated charcoal can be considered.

- Don't forget the common co-ingestions with DXM: Tylenol, anticholingerics and pseudoephedrine are all commonly seen in cough and cold medication.

- A urine drug screen may turn positive for PCP for these patients due to the similar chemical structure.