Global Health: Chagas Disease

/A Global Perspective

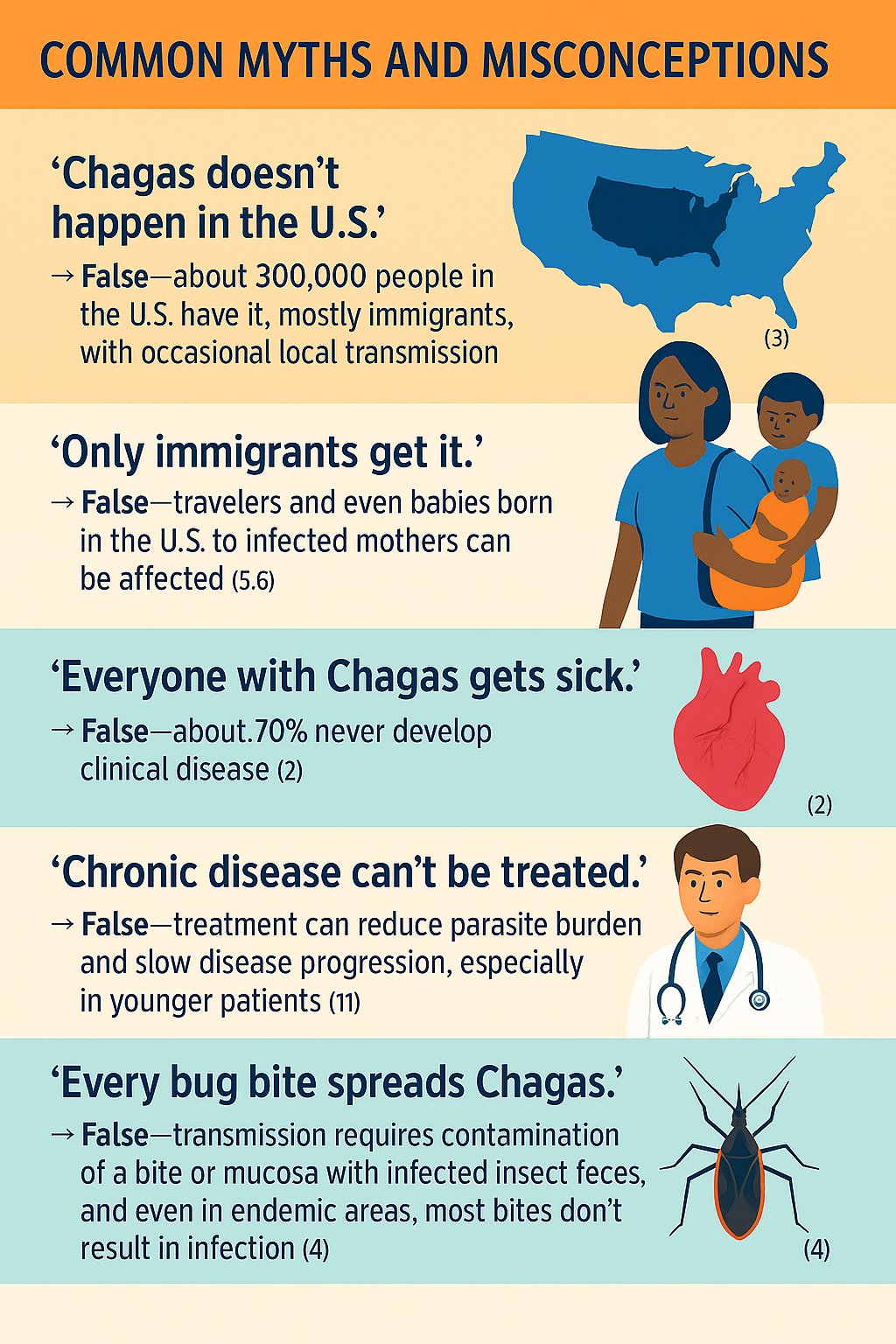

Chagas disease, or American trypanosomiasis, is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi and remains a major public health concern in Latin America. Thanks to vector control and improved housing, the number of people infected has dropped over the past few decades — from about 18 million in the 1990s to an estimated 6–7 million today. Annual incidence has also fallen, from roughly 200,000 to about 40,000 new cases per year. Still, the disease continues to affect tens of thousands each year, most commonly through insect-borne, congenital, or, transfusion. Alarmingly, as many as 70% of those infected don’t even know they have it (1,2). Migration has spread Chagas beyond rural areas and even outside of Latin America, with growing recognition of cases in urban settings and on other continents.

An American Perspective

In the U.S., an estimated 300,000 people are living with Chagas disease — mostly immigrants from endemic countries (3). Rare locally acquired cases have been reported, especially in southern states where triatomine “kissing bugs” and animal reservoirs are present, although U.S. vectors are generally less effective at transmitting the parasite (3,4). Congenital transmission is another important source of domestic cases. According to the CDC, about 43,000 women of childbearing age with chronic Chagas disease live in the US, and approximately 23% of infections occur through congenital transmission. Since blood donor screening began in 2007, transfusion-related infections have become rare (5). Nonetheless, underdiagnosis remains a big problem, and many patients go untreated — making physician awareness critical

An Ohio Perspective

Chagas is not endemic to Ohio. Although one species of triatomine bug (Triatoma sanguisuga) is found in the state, it rarely bites humans, and T. cruzi is uncommon in local wildlife. No locally acquired human infections have been documented. Clinicians should think about Chagas disease mainly in patients born in or with extended stays in endemic areas (6).

| Time Since Infection | Typical Phase | Findings / Complications |

|---|---|---|

| 0-8 weeks | Acute Phase | Often asymptomatic or mild. Possible fever, malaise, Romaña’s sign (rare), hepatosplenomegaly. |

| 8 weeks–10+ years | Indeterminate Phase | Parasite persists without symptoms. ~60–70% of infected individuals remain in this stage indefinitely. |

| 10–30 years post-infection | Chronic Phase (Cardiac) | ~20–30% develop cardiac complications:• Conduction abnormalities (e.g. RBBB, AV block)• Dilated cardiomyopathy• Ventricular arrhythmias (VT, VF)• Apical aneurysm (risk of thromboembolism)• Sudden cardiac death |

| 10–30 years post-infection | Chronic Phase (GI) | ~10% develop digestive complications:• Megaesophagus → dysphagia, aspiration• Megacolon → constipation, volvulus |

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Disease Phases - Acute and chronic

Acute phase (up to ~8 weeks)

Often asymptomatic or mild and nonspecific

Fever, fatigue, myalgias, vomiting, diarrhea, rash, decreased appetite, headache

Rarely, patients develop the classic painless unilateral eyelid swelling (Romaña’s sign)

Encephalitis may occur during the acute phase, accompanied by elevated levels of albumin, leukocytes, and trypomastigotes in the cerebral spinal fluid -CSF-

Acutely infected patients manifest difficulty in mental concentration, cephalgia, muscular disturbances (myoclonus, bradykinesia, dyspraxia), weakness, and speech disturbances

Headaches, seizures, lethargy, or mood changes are probably due to meningoencephalitis, exhibited by 5-10% of T. cruzi acutely infected patients

More frequently affects children under 2 years of age and is almost always fatal when coexists with myocarditis and cardiac insufficiency

Severe acute illness is unusual

Chronic phase: Patients can remain asymptomatic for years

About 20–30% develop cardiac disease including dilated cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, myocarditis and embolic events

Around 10% develop gastrointestinal complications such as megaesophagus or megacolon (2,7).

In one U.S. study of Latin American immigrants with newly diagnosed non‑ischemic cardiomyopathy, nearly 1 in 5 (≈19%) were found to have T. cruzi infection, and the group with Chagas cardiomyopathy had a >4‑fold higher hazard of death or heart transplant compared to non‑Chagas NICM (36% vs 10%) (3). These findings underscore the importance of including Chagas disease in the differential for NICM among at‑risk patients and highlight the elevated arrhythmic and mortality risk in Chagas‐associated cardiomyopathy

Diagnostic Approach

In the acute phase, parasitemia is high — so diagnosis can be confirmed by blood smear or PCR (8). In the chronic phase, parasitemia is low — so two positive serologic IgG tests (e.g., ELISA, IFA) are required. If results are inconclusive, a third test is recommended (9). In newborns, maternal antibodies may persist up to 12 months, so PCR in infancy or serology after 9–12 months is preferred to confirm congenital infection (10). Involving infectious disease may is also helpful in the work up and diagnosis of Chagas, as well as for patient follow up.

At the University of Cincinnati Medical Center, the EPIC order for Chagas testing is LAB3058, and it requires one gold top or one red top. This is a send out test.

Treatment and Management

Antiparasitic Therapy

Two drugs are available:

Benznidazole (preferred, for those under 50 and without cardiomyopathy): 5–7 mg/kg/day PO for 60 days (11)

Nifurtimox: 8–10 mg/kg/day PO for 60–90 days (12)

Both work best in the acute phase but are still recommended for most chronic infections, particularly in younger patients or those without advanced heart disease. It is important to recognize that the treatment of Chagas is meant for preventing worsening outcomes such as end organ damage. Once there is end organ damage, treatment is futile.

Side effects are common — rash, neuropathy, and GI upset with benznidazole; more neurologic and GI toxicity with nifurtimox (11,12). Neither should be used in pregnancy or severe liver/kidney disease (12).

Supportive Care

Manage cardiac and GI complications according to standard heart failure, arrhythmia, and surgical protocols (7). Multidisciplinary follow-up is often needed.

What Emergency Physicians Should Know

For ED clinicians, a high index of suspicion is key — especially when evaluating immigrants or travelers from endemic regions, or their children.

Red flags in the ED include:

New-onset heart failure, cardiomegaly, high-grade AV block, or ventricular arrhythmias in a middle-aged patient from an endemic country

Ischemic stroke or other embolic events in a young person with risk factors for Chagas.

Bowel obstruction, volvulus, or aspiration pneumonia suggestive of underlying megacolon or megaesophagus

Acute febrile illness in a newly arrived migrant or traveler (rare in the U.S.).

Chagas is not contagious through casual contact. Standard precautions suffice. Counsel patients to avoid donating blood or organs until evaluated and refer women of childbearing age for treatment to prevent congenital transmission.

POST BY Charlene Kotei, md

Dr. Kotei is a PGY-3 resident at the University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine Residency.

EDITING BY Whitney Bryant, MD MPH MEd

Dr. Bryant is an Associate Professor at the University of Cincinnati and Global Health Director at the University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine

References

World Health Organization. Chagas disease (American trypanosomiasis). WHO. Updated April 11, 2024. Accessed July 17, 2025. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis)

Pan American Health Organization. Chagas disease. PAHO. Updated December 2023. Accessed July 17, 2025. https://www.paho.org/en/topics/chagas-disease

Bern C, Montgomery SP. An estimate of the burden of Chagas disease in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49(5):e52-e54. doi:10.1086/605091

Montgomery SP, Parise ME, Dotson EM, Bialek SR. What do we know about Chagas disease in the United States? Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2016;95(6):1225-1227. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.16-0213

Montgomery SP, Stramer SL, Rotman J, et al. Declining incidence of transfusion-transmitted Chagas disease in the United States after implementation of screening. Transfusion. 2016;56(12):2966-2972. doi:10.1111/trf.13807

Ohio Department of Health. Chagas disease. ODH. Accessed July 17, 2025. https://odh.ohio.gov/know-our-programs/infectious-disease-control-manual/section3/chagas-disease

Rassi A Jr, Rassi A, Marin-Neto JA. Chagas disease. Lancet. 2010;375(9723):1388-1402. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60061-X

Bern C, Kjos S, Yabsley MJ, Montgomery SP. Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas’ disease in the United States. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(4):655-681. doi:10.1128/CMR.00005-11

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Parasites—American trypanosomiasis (also known as Chagas disease): diagnosis. CDC. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed July 17, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/chagas/health_professionals/dx.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Congenital transmission of Chagas disease—Virginia, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(26):477-479. Accessed July 17, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6126a3.htm

Bern C. Chagas’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(5):456-466. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1410150

Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Lampit (nifurtimox) for treatment of Chagas disease in pediatric patients. FDA. August 6, 2020. Accessed July 17, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-lampit-nifurtimox-treatment-chagas-disease-pediatric-patients