Esophageal Trauma in the Emergency Department

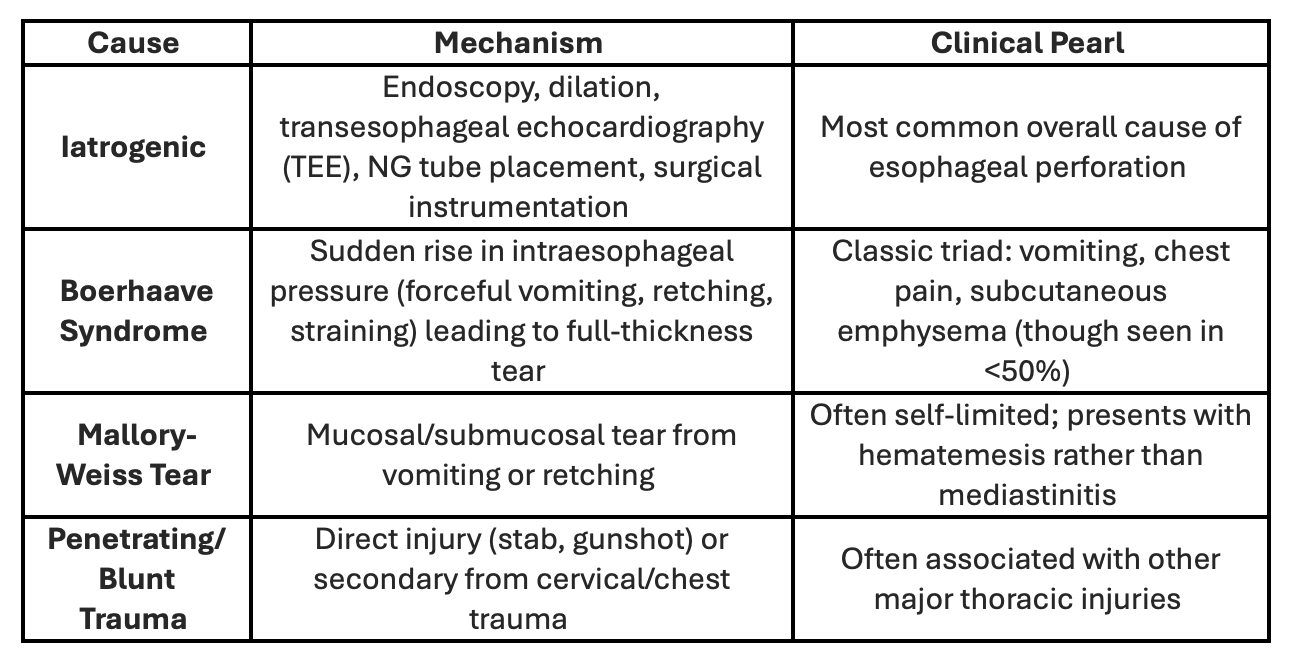

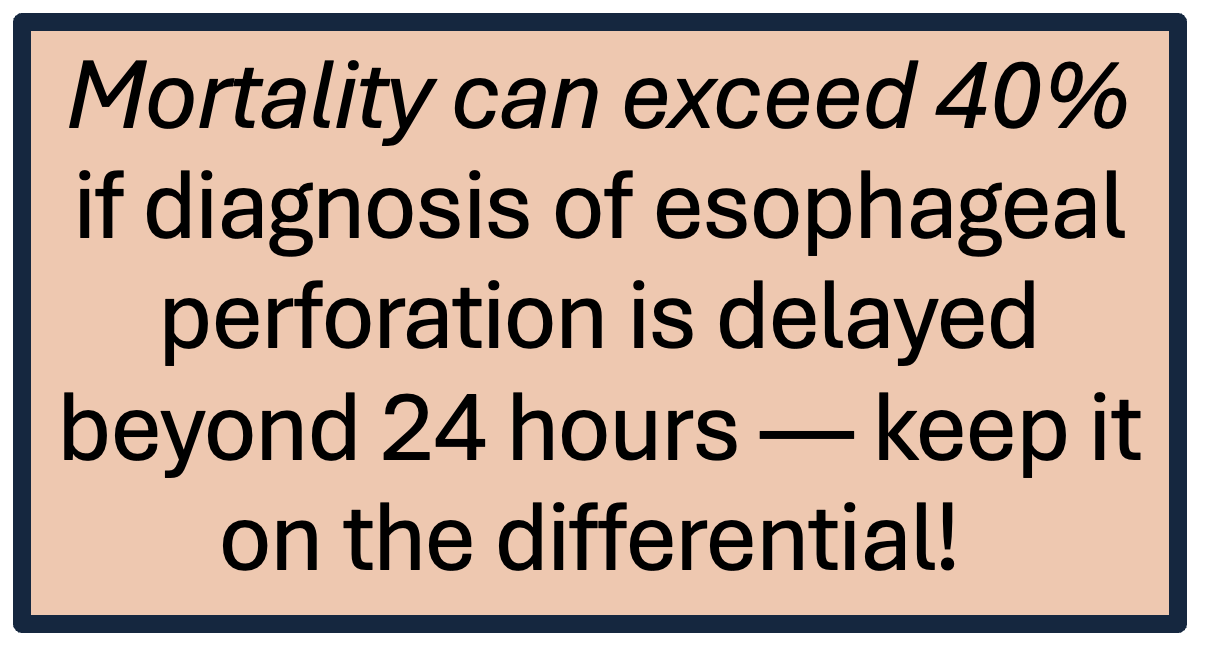

/While esophageal injuries are relatively rare, they can be devastating if missed. From the spontaneous tears of Boerhaave syndrome to the mucosal lacerations of Mallory-Weiss, recognizing and initiating treatment esophageal trauma quickly is critical. In the emergency department, prompt diagnosis and management can mean the difference between a full recovery and rapid decompensation.

ANATOMY, epidemiology, and Common Mechanisms of Esophageal Injury

It can be easy to forget about the esophagus until it’s the source of the problem. Then suddenly, a simple episode of vomiting or an “easy” endoscopy becomes a race against the clock.

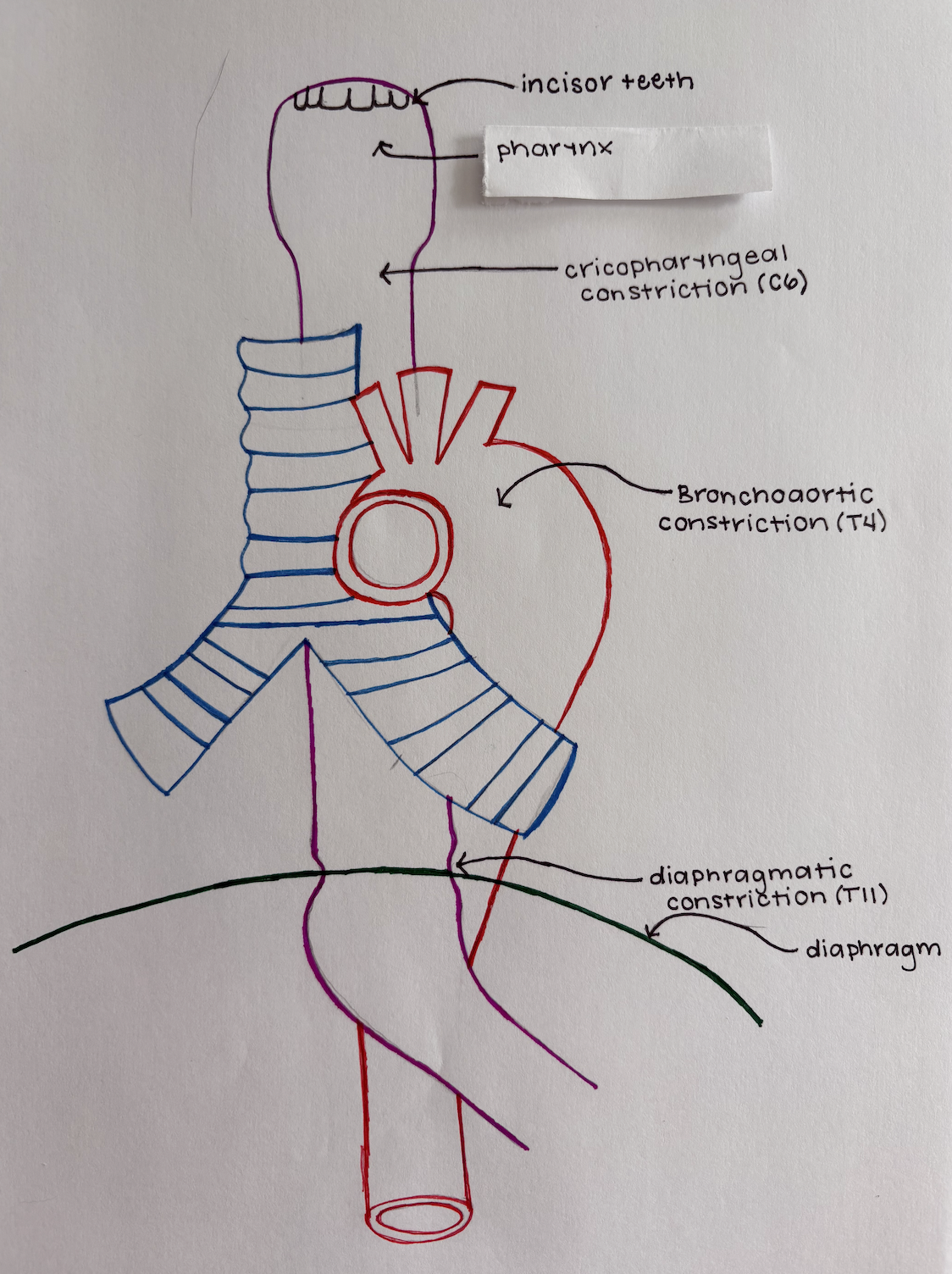

The esophagus itself spans roughly 25 cm from C6 to T10, and its vertical course through the neck, chest, and diaphragm with three natural constriction points makes it particularly vulnerable to shear forces and pressure-related rupture especially during instrumentation and forceful vomiting.

Natural Constriction Points:

Cricopharyngeal constriction (C6): At the level of the upper esophageal sphincter, just below the pharynx. This is a common site for iatrogenic injury during endoscopy or intubation.

Bronchoaortic constriction (T4): Where the esophagus is compressed by the aortic arch and left main bronchus. This fixed point is susceptible to shear forces.

Diaphragmatic constriction (T11): At the gastroesophageal junction, where the esophagus passes through the diaphragm. This is the classic site of rupture in Boerhaave syndrome.

Iatrogenic causes, particularly endoscopy-related, account for nearly 60% of all esophageal perforations. The most frequently affected regions are the hypopharynx and distal esophagus, aligning with the first and third constrictions. Intrathoracic tears are most common (54%), followed by cervical (27%) and intraabdominal (19%) injuries. While external trauma rarely leads to perforation, ingested foreign bodies—especially fish bones—are responsible for about 12% of cases.

Mallory-Weiss Tears:

Definition: A longitudinal mucosal tear, usually at the gastroesophageal junction.

Etiology: Sudden increase in intra-abdominal pressure — vomiting, coughing, or straining.

Presentation: Hematemesis after retching, typically without severe chest pain.

Diagnosis: Best confirmed with upper endoscopy, but many resolve before intervention.

Management:

Most resolve spontaneously.

Supportive care: IV fluids, antiemetics, acid suppression (PPIs).

Endoscopic therapy (clips, epinephrine injection) if bleeding persists.

Key point: Mallory-Weiss tears are mucosal, not full-thickness — think “bloody but benign” compared to Boerhaave.

Boerhaave Syndrome:

This is the classic full-thickness esophageal rupture after forceful vomiting — and it’s a true emergency.

Clinical Features:

Sudden, severe retrosternal chest pain after vomiting.

Subcutaneous emphysema (“crunching” on palpation).

Mediastinal air may produce the Hamman crunch — a precordial crackling sound with each heartbeat.

Rapid progression to sepsis and shock if untreated.

Diagnosis:

CT chest with contrast (water-soluble, not barium) → identifies extraluminal air or contrast leak.

CXR findings: Pneumomediastinum, pleural effusion, widened mediastinum.

Avoid NG tube insertion or blind instrumentation if perforation is suspected.

Management:

Broad-spectrum antibiotics (covering oral and GI flora) +/- anti-fungals

NPO + surgical consultation early.

Operative vs. nonoperative management:

Surgery for large or contained ruptures, mediastinitis, or hemodynamic instability.

Nonoperative if contained leak, minimal symptoms, and early diagnosis.

Iatrogenic Esophageal Injuries: The Unseen Majority

While Boerhaave grabs the headlines, iatrogenic trauma as mentioned above is the quiet majority of esophageal injuries.

Common Sources

Endoscopic perforation (EGD, dilation, variceal banding)

Nasogastric tube placement (especially with resistance)

Trans-esophageal echocardiography (TEE)

Surgical instrumentation or intubation mishaps

Diagnosis & Management

Often discovered intra-procedurally or due to post-procedure neck/chest pain, crepitus, or dysphagia.

CT with contrast remains the gold standard.

Management depends on location and severity:

Small, contained injuries → conservative care (NPO, IV antibiotics, observation).

Larger or uncontained perforations → surgical or endoscopic repair.

Tip: If a patient develops neck pain, crepitus, or fever after a recent endoscopy — think esophageal perforation until proven otherwise.

Key Takeaways

Esophageal injuries are rare but deadly if missed — early imaging and surgical consultation save lives.

Mallory-Weiss: mucosal tear, usually self-limited GI bleed.

Boerhaave: full-thickness rupture, rapidly fatal without prompt management.

Iatrogenic: most common overall but often caught earlier.

Always use water-soluble contrast if imaging for suspected perforation.

When in doubt — call CT surgery or GI early and keep the patient NPO.

POST BY emma fitz, md

Dr. Fitz is a PGY-1 resident at the University of Cincinnati Emergency Medicine Residency.

EDITING BY ANITA GOEL, MD

Dr. Goel is an Associate Professor at the University of Cincinnati, a graduate of the UC EM Class of 2018, and an assistant editor of Taming the SRU.

References

Brinster CJ, Singhal S, Lee L, et al. Evolving options in the management of esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77(4):1475–1483.

Brauer RB, Liebermann-Meffert D, Stein HJ, Bartels H, Siewert JR. Boerhaave’s syndrome: Analysis of the literature and report of 18 new cases. Dis Esophagus. 1997;10(1):64–68.

Mavrelos K, Hall C, et al. Iatrogenic esophageal perforation: management strategies and outcomes. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(5):2403–2412.

Nandi P, Ong GB. Iatrogenic perforation of the oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1978;65(3):179–182.

Cappell MS, Friedel D. Mallory-Weiss tear: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(3):491–509.

Markar SR, Mackenzie H, Wiggins T, et al. Management and outcomes of esophageal perforation: a national study of 2,564 patients in England. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(11):1559–1566.