Annals of B Pod: Retzius Abscess

/HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS

The patient is a male in his 40s with a past medical history of intravenous drug use (IVDU) who presents to the emergency department with chief complaints of dysuria and inguinal pain. The patient reports that his symptoms started approximately 10 days ago after he helped a friend put up fencing in his yard. He describes the pain as a stretching sensation in his bilateral inguinal regions that has progressively worsened. He additionally reports weakness of the lower extremities, worse on the right compared to the left, which he attributes to be secondary to this pain. He denies associated numbness or tingling, and has no saddle anesthesia, bowel or bladder incontinence, fevers, chills, or back pain. He complains of dysuria, described as a burning sensation, which has occurred for the past four days. He has no constipation, diarrhea, shortness of breath, or chest pain. The patient had to be lifted out of his car and brought into the emergency department on a stretcher due to inability to bear weight on his lower extremities secondary to severe pain.

Past Medical History: IV Drug Use

Past Surgical History: None

Medications: None

Allergies: Penicillin (hives)

Social History: Intravenous heroin one hour prior to arrival; smokes marijuana, unspecified frequency of use; patient denied alcohol use; smokes 1 pack per day of cigarettes.

PHYSICAL EXAM

Vitals: T 99.7F HR 120 BP 155/90 RR 24 SpO2 97% on RA

The patient is ill-appearing, but alert and in no acute distress. His HEENT exam is unremarkable. Cardiovascular exam demonstrates strong distal pulses and tachycardia. He is in no respiratory distress and had normal breath sounds. His abdomen is soft and nondistended without tenderness or guarding. No hernias are appreciated in the inguinal region. Neurologic exam demonstrates a normal cranial nerve exam, with intact sensation to light touch in all four extremities. Motor exam demonstrates weakness of hip flexion, more pronounced on the right compared to the left (felt to be secondary to pain). Plantar flexion and extension is intact and equal bilaterally. He is unable to bear weight for gait testing secondary to pain.

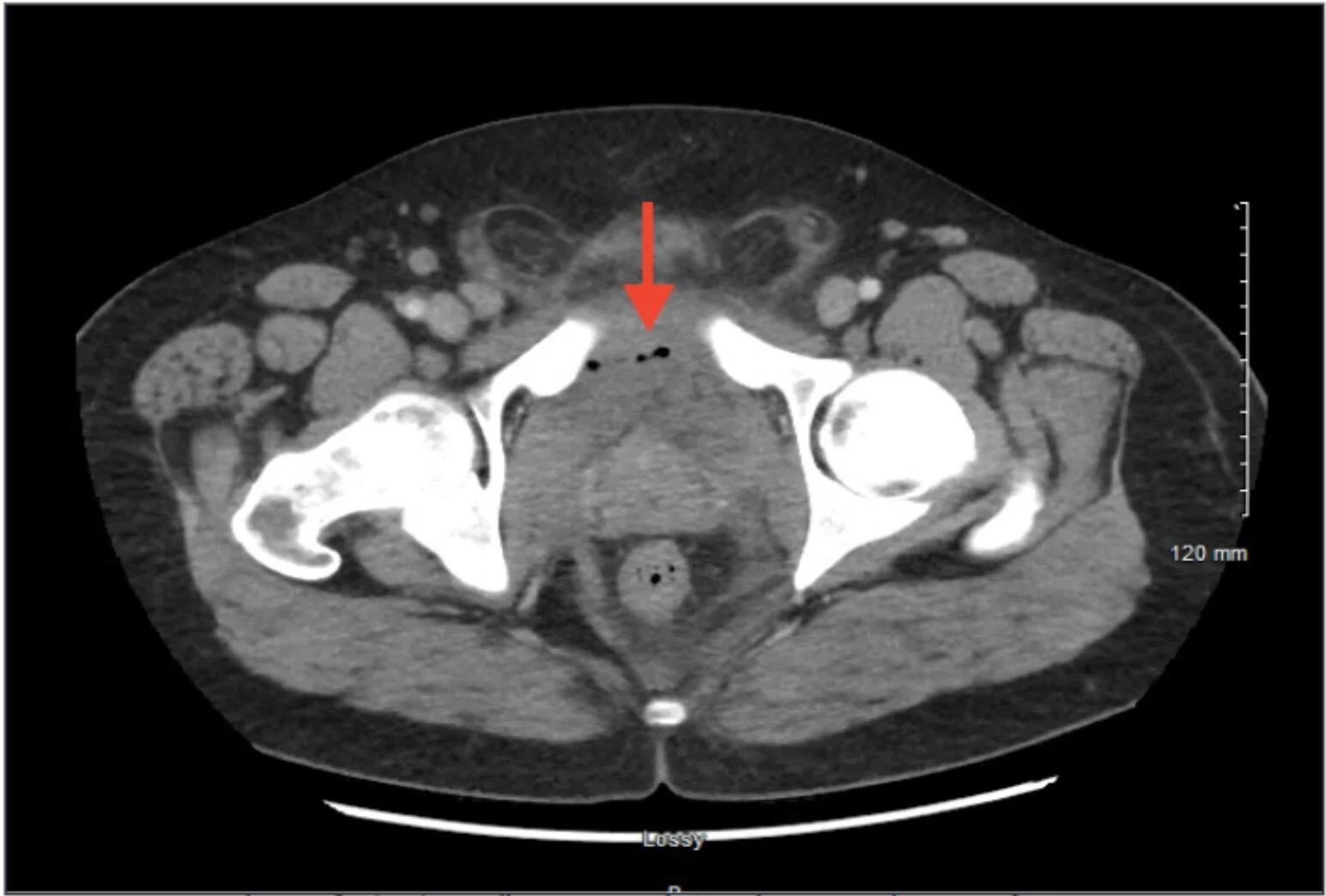

IMAGE 1: SAGGITAL CT IMAGE OF ENHANCING FLUID COLLECTION WITH ADJACENT FAT STRANDING ANTERIOR TO THE BLADDER

DIAGNOSTICS

WBC: 26 Hgb: 11 Hct: 34 Plt: 445

Na: 134 K: 3.9 Cl: 93 CO2: 27 BUN: 18 Crt: 0.90 Glu: 123

Lactate: 1 CRP: 287 ESR: 65

UA: Unremarkable

Blood cultures: + methicillin-sensitive staphylococcus aureus (MSSA)

EKG: Sinus tachycardia, normal axis and intervals, no ST segment or T wave changes.

HOSPITAL COURSE

The patient’s history of IVDU, tachycardia, leukocytosis, and elevated inflammatory markers (ESR, CRP) with severe inguinal pain and dysuria were concerning for a pelvic or intra-abdominal infection. This was confirmed by CT, as the CT demonstrated a retropubic abscess secondary to septic arthritis of the pubic symphysis (see Image 1). The patient was started on vancomycin and ceftriaxone after blood cultures were drawn, and the orthopedics service was consulted for management. They recommended admission and interventional radiology consultation to percutaneously drain the extraperitoneal fluid collection.

DISCUSSION

Pathophysiology

The space of Retzius is bordered externally by the transversalis fascia and internally by the parietal peritoneum of the abdomen. It is also known as the prevesical space, as it lies anterior to the urinary bladder, or the retropubic space, with its position posterior to the pubic symphysis. It is considered to be an extraperitoneal space and normally contains fat and blood vessels. Abscess formation in this site is relatively rare, but has been described in the literature through various case reports. [1,2,3] As seen in the case described in this article, abscess formation can arise from septic arthritis or osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis due to its adjacent contact with this space. Inflammation and infection of the pubic symphysis can arise from repetitive trauma, urologic or gynecologic surgery, urachal infections, or pregnancy. [4] Other pelvic infections, such as perianal abscesses or Fournier’s gangrene, can spread into the space of Retzius and cause infection. [5] IVDU and immunosuppression may promote hematogenous spread and seeding of fibrocartilaginous joints like the pubic symphysis. The bacterial etiology of the abscess often depends on the associated inciting infection. For example, pubic symphysis osteomyelitis causing a retropubic abscess in a patient who uses drugs intravenously would be more likely to be secondary to a bacterium such as staphylococcus (as in this case), whereas a Fournier’s gangrene spreading to the prevesical space would likely be polymicrobial to include gram-negative anaerobes.

Clinical Presentation

The patient typically presents with pubic or groin pain, although the symptoms may be vague, insidious, and difficult to discern. The pain may progress to be severe enough to impact ambulation and normal gait. Strength testing can be impaired secondary to pain, particularly in the hip adductors and flexors. [6] Dysuria, increased urinary frequency, and a sensation of incomplete bladder emptying may be experienced by the patient due to mechanical pressure on the bladder or its outlet from the adjacent abscess in the prevesical space. [3] Systemic symptoms such as malaise, fevers, and chills can occur, especially with hematogenous infection. The pubic symphysis and suprapubic area are typically tender to palpation. Bowel function is usually normal.

Diagnostic Evaluation

example image showing APPROXIMATELY a 5 CM FLUID & GAS COLLECTION ON AXIAL CT IN THE PREVESICULAR SPACE OF RETZIUS

Laboratory evaluation is typically consistent with infection, with leukocytosis and neutrophilia found on CBC. Thrombocytosis may indicate ongoing inflammation as an acute phase reactant. Other nonspecific markers of inflammation such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) may be elevated in response to this bacterial infection. C-reactive protein is a protein released by the liver that binds to dead or dying bacteria to trigger the complement system; its elevation, while nonspecific, suggests an ongoing bacterial infection. [7] Similarly, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, which is the measure of how fast red blood cells (RBCs) fall to the bottom of a tube in a sample of blood, is typically elevated in infection due to increased inflammatory proteins in the blood, such as fibrinogen. These inflammatory proteins cause the RBCs to clump together and fall at a faster rate, thereby increasing the ESR. Urinalysis typically does not suggest infection, as the urinary symptoms are caused by mechanical compression as opposed to acute cystitis.

The test of choice for diagnosis of abscess in the space of Retzius in the ED is a CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast. This will also assist with evaluation of septic arthritis or osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis and will evaluate for other intra-abdominal abscesses or fluid collections. MRI is another potential diagnostic modality to evaluate for osteomyelitis and adjacent abscess, although it is typically less available in the standard emergency department compared to CT.

Treatment

Percutaneous drainage of the abscess is the recommended approach for treatment. [8] More invasive surgeries predispose the patient to further infections and complications. Blood cultures should be drawn, and the patient should be started on broad-spectrum antibiotics due to the multiple potential causes of this extraperitoneal infection. MRSA coverage should be present with an agent such as vancomycin, as hematogenous seeding of the pelvic bones can cause osteomyelitis with adjacent Space of Retzius abscess, as described in this case. This abscess can also be a result of contiguous spread of perirectal or perineal infection such as Fournier’s gangrene; therefore, gram negative anaerobes should also be covered with an agent such as zosyn. [9] In summary, recommended antibiotic regimens to cover suspected organisms would be vancomycin and zosyn or a combination of vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole. The patient may require a prolonged course of antibiotics if accompanying osteomyelitis is present.

SUMMARY

The space of Retzius is located anterior to the bladder and posterior to the pubic symphysis. Abscesses can form in this extraperitoneal space, causing pelvic or inguinal pain, gait disturbance, urinary symptoms, and constitutional symptoms in affected patients. Immunocompromise, IVDU, and other chronic conditions such as diabetes or end-stage renal disease may predispose patients to this infection, or it may occur spontaneously. Laboratory evaluation may be suggestive of active infection, with elevated inflammatory and infectious markers. A CT scan with IV contrast is preferred to diagnose this condition in the emergency department. IV antibiotics and percutaneous drainage are the primary treatment modalities. By understanding pelvic space anatomy and carrying a high index of suspicion for the disease, the emergency clinician can more accurately evaluate and diagnose extraperitoneal abscesses such as those in the space of Retzius.

AUTHORED BY KRISTEN MEIGH, MD

Dr. Meigh is a PGY-3 in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati

EDITING BY THE ANNALS OF B POD EDITORS

REFERENCES

1. Rising EH. Prevesical abscess. Ann Surg. 1908; 48: 224-36

2. Lorenzo, Gustavo Ph.D.; Meseguer, María A. M.D.; del Rio, Pedro M.D.; Sánchez, Juan Ph.D.; de Rafael, Luis M.D. Prevesical abscess secondary to pubis symphysis septic arthritis, The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2000; 19(9): 896-898

3. Pimentel torres J, Morais N, Cordeiro A, Lima E. Abscess originating from osteomyelitis as a cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and acute urinary retention. BMJ Case Rep. 2018

4. Sexton DJ, Heskestad L, Lambeth WR, McCallum R, Levin LS, Corey R. Postoperative pubic osteomyelitis misdiagnosed as osteitis pubis: report of four cases and review. Clin Infect Dis 1993; 17: 695–700.

5. Oikonomou C, Alepas P, Gavriil S, et al. A Rare Case of Posterior Horseshoe Abscess Extending to Anterolateral Extraperitoneal Compartment: Anatomical and Technical Considerations. Ann Coloproctol 2019; 216-220.

6. Choi H, Mccartney M, Best TM. Treatment of osteitis pubis and osteomyelitis of the pubic symphysis in athletes: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2011; 45(1): 57-64.

7. Paydar-Darian N, Kimia AA, Monuteaux MC, et al. C-reactive protein or erythrocyte sedimentation rate results reliably exclude invasive bacterial infections. Am J Emerg Med. 2019; 37(8): 1510-1515.

8. Sartelli M, Chichom-mefire A, Labricciosa FM, et al. The management of intra-abdominal infections from a global perspective: 2017 WSES guidelines for management of intra-abdominal infections. World J Emerg Surg. 2017; 12:29.

9. Hamza E, Saeed MF, Salem A, Mazin I. Extraperitoneal abscess originating from an ischorectal abscess. BMJ Case Rep. 2017.