Annals of B Pod: Polycythemia

/HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS

The patient is an otherwise healthy female in her late 50s who presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of bilateral posterior neck pain, odynophagia, and dysphagia with solid foods over the previous two weeks. She describes the neck pain as constant, 10/10 pain which has been progressively worsening, is exacerbated by movement, and is not alleviated by Tylenol or Ibuprofen. She also vomited twice a few days ago. She denies fever, nausea, abdominal pain, dysuria, hematuria, constipation, or diarrhea.

PAST MEDICAL HISTORY: None

PAST SURGICAL HISTORY: Hysterectomy

MEDICATIONS: None

ALLERGIES: Penicillin

PHYSICAL EXAM

Vitals: T 97.2 F HR 80 BP 150/82 RR 18 SpO2 100% RA

The patient is a thin female in no acute distress. Her pupils are equal, round, and reactive to light. Cranial nerves are intact, and her voice is clear without aphasia or dysphonia. She has 5/5 strength and intact sensation throughout bilateral upper extremities. No trismus is appreciated. Mucous membranes appear dry. Range of motion of the neck is limited, but there is no nuchal rigidity. She is exquisitely tender to palpation over the paraspinal musculature and soft tissues of the neck. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, and abdominal exam are within normal limits.

NOTABLE DIAGNOSTICS

WBC 5.4 RBC 7.18 Hgb 22.7 Hct 67.1 RDW 16.9 Plt 85

Na 138 K 3.8 Cl 101 CO2 29 BUN 7 Cr 0.88 Glu 82

Ca 9.5 PO4 3.4 Albumin 3.7 HIV 1 + 2 Non-reactive

HOSPITAL COURSE

The patient was given ketorolac with subsequent improvement in her neck pain and normalization of the range of motion of her neck. A nasopharyngeal scope was performed at bedside which showed no edema, masses or abnormalities of the vocal cords, epiglottis, or posterior pharynx. Contrasted CT imaging of the neck was normal. However, lab workup revealed an incidental finding of polycythemia. Although the workup for her neck pain was negative and her pain significantly improved, the patient was admitted to hospital medicine for further evaluation and management of her incidental polycythemia.

Hematology was consulted and recommended outpatient transthoracic echocardiography to evaluate for a shunt, carboxyhemoglobin, and JAK 2 level. Phlebotomy of 500mL was performed with replacement of crystalloid due to the extent of her polycythemia. The patient was discharged two days later, without any apparent complications, with plans to follow up in the outpatient setting with hematology for likely primary polycythemia. At that time, polycythemia vera and EPO-driven polycythemia were thought to be the most likely etiologies.

Results later demonstrated a normal echocardiogram, carboxyhemoglobin of 3.5% (normal value < 2% as the patient is not a smoker), normal JAK 2, normal EPO levels, negative testing for BCR-ABL, and CT abdomen/pelvis negative for splenomegaly. She declined bone marrow biopsy, so the etiology of her polycythemia remains unknown. She continues to be managed with intermittent phlebotomy. Since her initial visit, she has also had seizures and was found to have subdural hygromas and evidence of prior CVAs. She has also had intermittent ED visits for neck pain, which have been thought to be secondary to occipital neuralgia.

DISCUSSION

Pathophysiology and Definitions

Polycythemia, also called erythrocytosis, is an abnormally elevated level of hemoglobin or hematocrit in the circulating peripheral blood. Polycythemia can be classified into relative polycythemia, which is generally secondary to volume depletion, and absolute polycythemia, which can arise from primary myeloproliferative disorders or in response to hypoxia from a number of secondary causes. [1] Although the majority of patients are found to have polycythemia incidentally, a small percentage present to the ED with acute thrombotic events, which are a rare but well-recognized complication of both primary and secondary polycythemia.

Polycythemia is a laboratory-based diagnosis, defined as hemoglobin >16.5g/dL in men, >16g/dL in women or hematocrit >49% in men, >48% in women. [1] It is important to recognize that both hemoglobin and hematocrit are not direct measures of red blood cells (RBCs). Instead, they more accurately depict the percentage or relative value of the circulating blood volume that is comprised of RBCs. A patient can have a relative polycythemia resulting from decreased plasma volume (hemoconcentration), most commonly due to dehydration, vomiting, diarrhea or diuretic use. Although patients with polycythemia often have an elevated RBC count, the RBC count alone can be appropriately elevated in physiologic response to anemia, and therefore must be elevated in conjunction with an elevated hemoglobin or hematocrit in order to be diagnostic.

Absolute polycythemia (a true increase in red blood cell mass) can be further divided into primary and secondary causes. Primary polycythemias are caused by mutations in the RBC progenitor cells that result in an increased total RBC mass. The most well-characterized of these entities is polycythemia vera (PV), which is due to a JAK2 mutation. However, many other myeloproliferative disorders can result in primary polycythemia.

Figure 1: Erythromelalgia (Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

Secondary polycythemia is an increased RBC mass in response to elevated serum erythropoietin (EPO) levels, which is usually secondary to tissue hypoxia. Common preceding conditions leading to secondary polycythemia include smoking, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and carbon monoxide exposure. Patients residing at high altitude live in a relatively hypoxic environment and can demonstrate elevated, non-pathologic baseline levels of both hemoglobin and hematocrit. In order to account for this, the reference upper limit for hemoglobin should be increased by approximately 1.0g/dl for patients living between 7500 and 10000 feet of altitude and by approximately 2.0g/dl for patients living at 10000-12000 feet. [2] EPO is produced by the kidneys, so patients with chronic renal insufficiency or a subacute insult to the renal parenchyma can also present with a secondary polycythemia. Secondary polycythemia may also result from EPO levels which are inappropriately elevated secondary to a paraneoplastic syndrome from an EPO-secreting malignancy. The malignancies most commonly implicated include renal cell carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and pheochromocytoma. Finally, secondary polycythemia can be seen in athletes who undergo autologous blood transfusions or exogenous EPO administration (also known as blood doping). Regardless of the cause of an absolute polycythemia, the increased RBC mass leads to hyperviscosity of the blood, placing the patient at increased risk of thrombotic events.

Clinical Presentation

In the Emergency Department, polycythemia most often presents as an incidental finding. It is important to attempt to differentiate between relative and absolute polycythemia, as only the latter confers a significant thrombotic risk. This can be accomplished by treating with intravenous fluids and retesting; improvement following fluid resuscitation indicates a relative polycythemia. In addition to volume depletion, chronic carbon monoxide exposure (such as smoking history or environmental exposures), chronic hypoxia, and occult malignancy should all be considered during the initial evaluation of a patient with undifferentiated polycythemia.

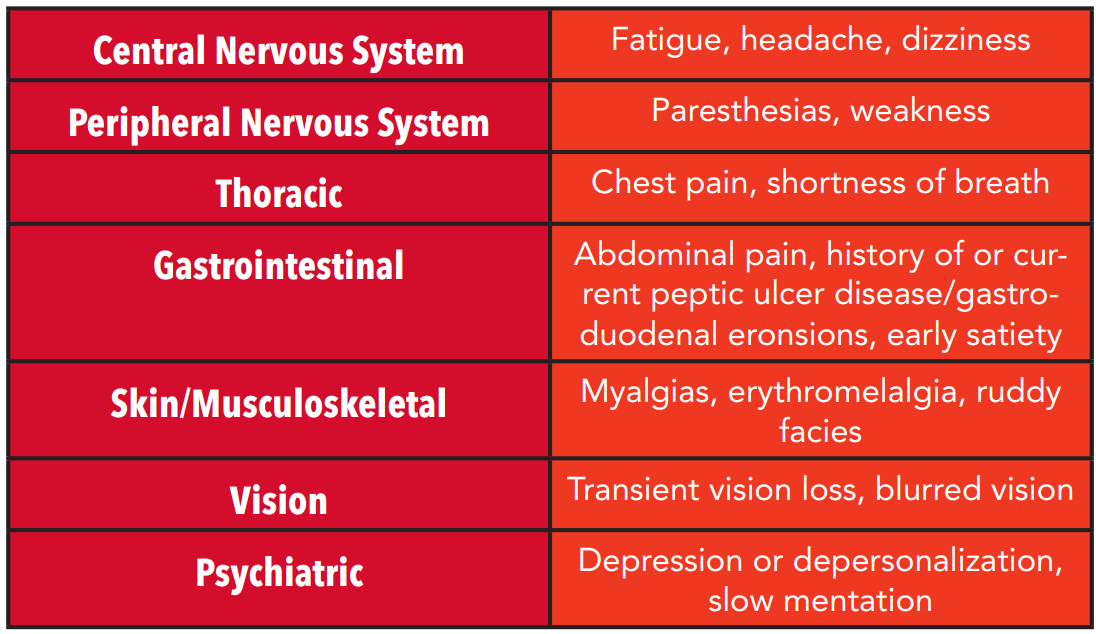

Table 1: Hyperviscosity symptoms by system

Patients with absolute polycythemia may present with symptoms of hyperviscosity (see table 1). Specific symptoms in polycythemia vera include pruritus after bathing (either with hot or cold water) and erythromelalgia (Figure 1). Some studies suggest these symptoms are present in approximately one third of patients with PV at the time of diagnosis and can often precede other manifestations of the disease by months to years. [3,4] Erythromelalgia is considered to be pathognomonic for PV and is described as an intense burning pain, often isolated to the hands and feet, associated with either rubor or pallor of those extremities. [4] In patients with erythromelalgia, there is no evidence of neurovascular dysfunction.

Patients with absolute polycythemias may present with acute thrombotic events. Between 7 and 16 percent of patients with PV are noted to have an arterial or venous thrombotic event at or before the time of diagnosis. [5] These events more commonly occur in the mesenteric, hepatic or portal vasculature. In patients who are young, female or otherwise relatively healthy and without comorbidities, new diagnoses of Budd-Chiari syndrome, portal vein thrombosis or mesenteric ischemia should trigger concern for a possible hyperviscous state such as polycythemia vera. [6] Absolute polycythemia is a known risk factor for pulmonary embolism, deep vein thrombosis, acute myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke.

Management & Disposition

Patients with relative polycythemia do not typically require further evaluation or admission for polycythemia alone. ED evaluation of patients with incidentally-discovered, asymptomatic absolute polycythemia can reasonably be limited to a CBC, renal profile and walking pulse oximetry, with consideration for carboxyhemoglobin levels.

Patients with polycythemia have up to a 28% incidence of thrombotic events and an approximately 8% chance of a major hemorrhage related to their disease. [4] Therefore, admission is appropriate for symptomatic patients, either with hallmark signs of PV or with hyperviscosity symptoms, and for patients with hematocrit >= 60g/dl. These patients can be started on low-dose aspirin in the emergency department, which provides symptomatic relief and decreases the thrombotic risk. [7]

Acute thrombi in patients with polycythemia are managed similarly to patients who lack this risk factor, with the exception of phlebotomy. Phlebotomy is indicated for patients with thrombotic complications and to maintain normal hematocrit levels in patients with primary polycythemias. While the need for phlebotomy may be an indication for admission, it is generally considered to be outside the scope of practice of an emergency physician. General guidance suggests that during the diagnostic workup phase, phlebotomy can be used to lower hematocrit levels to <60% until definitive diagnosis is reached, after which target hematocrit should be approximately 45%. [8] Phlebotomy treatments involve the removal of large quantities of blood, usually 250-500 cc, followed by 1:1 replacement with a crystalloid fluid. Conventional wisdom is that the expected reduction in hematocrit is three percentage points per 500mL blood removed. Dual-antiplatelet agents are not routinely recommended in patients with polycythemia due to an increased risk of hemorrhage, but there is some evidence that this may be helpful in certain patients. [9]

SUMMARY

Polycythemia is most frequently found incidentally, and can be relative or absolute. Absolute polycythemia has both primary and secondary causes, and if left unmanaged can cause symptoms of hyperviscosity and increased risk of thrombotic events. Treatment depends on the underlying cause and may include anti-platelet agents and phlebotomy.

AUTHORED BY OLIVIA URBANOWICZ, MD

Dr. Urbanowicz is an Education Fellow in Emergency Medicine at the University of Cincinnati

EDITING BY THE ANNALS OF B POD EDITORS

REFERENCES

1. Djulbegovic M, Dugdale LS, Lee AI. Evaluation of Polycythemia: A Teachable Moment. JAMA internal medicine. 2018 Jan 1;178(1):128-30.

2. Sullivan KM, Mei Z, Grummer‐Strawn L, Parvanta I. Haemoglobin adjustments to define anaemia. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2008 Oct;13(10):1267-71.

3. Siegel FP, Tauscher J, Petrides PE. Aquagenic pruritus in polycythemia vera: characteristics and influence on quality of life in 441 patients. American journal of hematology. 2013 Aug;88(8):665-9.

4. Yesilova AM, Yavuzer S, Yavuzer H, Cengiz M, Toprak ID, Hanedar E, Ar MC, Baslar Z. Analysis of thrombosis and bleeding complications in patients with polycythemia vera: a Turkish retrospective study. International journal of hematology. 2017 Jan 1;105(1):70-8.

5. Tefferi A, Rumi E, Finazzi G, Gisslinger H, Vannucchi AM, Rodeghiero F, Randi ML, Vaidya R, Cazzola M, Rambaldi A, Gisslinger B. Survival and prognosis among 1545 patients with contemporary polycythemia vera: an international study. Leukemia. 2013 Sep;27(9):1874-81.

6. Landolfi R, Di Gennaro L, Nicolazzi MA, Giarretta I, Marfisi R, Marchioli R. Polycythemia vera: gender-related phenotypic differences. Internal and emergency medicine. 2012 Dec;7(6):509-15.

7. Van Genderen PJ, Mulder PG, Waleboer M, Van De Moesdijk D, Michiels JJ. Prevention and treatment of thrombotic complications in essential thrombocythaemia: efficacy and safety of aspirin. British journal of haematology. 1997 Apr;97(1):179-84.

8. Marchioli R, Finazzi G, Specchia G, Cacciola R, Cavazzina R, Cilloni D, De Stefano V, Elli E, Iurlo A, Latagliata R, Lunghi F. Cardiovascular events and intensity of treatment in polycythemia vera. N Engl J Med. 2013 Jan 3;368:22-33.

9. Pedersen OH, Larsen ML, Kristensen SD, Hvas AM, Grove EL. Recurrent cardiovascular events despite antiplatelet therapy in a patient with polycythemia vera and accelerated platelet turnover. The American journal of case reports. 2017;18:945.