Annals of B-Pod: Approach to the Febrile Infant

/Setting the Scene

Imagine it’s your first moonlighting shift at a small rural community hospital. The nearest referral center for both adults and children is 90-minutes away by ground. The annual census of the emergency department is 15,000 patients per year, of which only 5% is pediatric. There are 2 hours left in your 12-hour shift and your energy is all but spent. You are looking forward to winding down at home after an extremely busy and high-acuity shift when your 35th patient of the day checks in. The patient’s chief complaint is fever. You give yourself an internal fist pump thinking that you’re about to see your 12th viral URI of the day and that you’ll be in-and-out of that room no in time. In the midst of your premature celebration you scan the nursing note and see the age of the patient: 6 weeks…You’re hopes of a quick and easy disposition suddenly melt away leaving you with many more questions regarding this patient’s care than answers…You muster your remaining energy and make your way toward the patient’s room.

You walk in the room...

The patient is an otherwise healthy ex-full term 6-week old male. The mother denies any prenatal or neonatal complications. Patient has been in a good state of health until yesterday evening when he became irritable, febrile, and refused oral intake. These symptoms have persisted throughout the last 24 hours with a Tmax of 103. When asked about associated symptoms the mother endorses decreased urine output and periods of decreased activity. She denies cough, rash, cyanosis, decreased body tone, diarrhea, bloody stool, foul-smelling urine, and seizures. The patient has not yet received his 2 month shots. There has been no recent travel and no known sick contacts.

Physical Exam

T 102.5 HR 180 BP 70/45 RR 45 O2 Sat 97%

The infant is intermittently irritable but consolable. He does not interact or make eye contact with the care provider and only intermittently with the mother and is appropriately sized for his age. His fonteanelles are flat, he has mild erythema of both tympanic membranes, mild clear rhinorrhea, normal conjunctiva, a normal oropharyx and pupils are equal, round, and reactive to light. He has non-labored breathing without retractions faint wheezing at the right lung base but his lungs are otherwise clear to auscultation. His cardiac exam reveals a regular tachycardia without any murmurs, rubs, or gallops. His abdomen is soft and non-tender without any masses or hepatosplenomegaly. His extremities are well perfused, he has brisk cap refill. His skin, neck, and neurological exam are all normal.

Now What?

As you finish your assessment with tears welling in her eyes the mother asks you “is he going to be OK?” You want to tell the mother that everything is fine, but at the same time you know that your assessment wasn’t 100% reassuring. Although your suspicion is low, you cannot rule out a serious bacterial infection (SBI) at this point. As you sit next to the mother carefully contemplating what to say, your phone rings. “Thank God!”, you tell yourself and you rush out of the room. And as you make your way back to your work station a flood of questions regarding management of the febrile infant hit you all at once…

Q&A with the Experts in Pediatric Emergency Medicine at Cincinnati Children's Hospital

You have no identifiable source of infection. The differential ranges from otitis media, to UTI, to early pneumonia, to bacteremia, to meningitis. What is the incidence of SBI in this patient population? What labs, if any, are indicated in this patient population?

“In a large meta-analysis of infants less than three months of age with fever without a source (>54,000 patients) published in 2012 by Hui et al., the authors found the prevalence of SBI to be 9.4%. Notably, they found that those less than two weeks had the highest prevalence of SBI (25%), while those less than one month (13%) and between one and three months (7.1%) had less prevalence of disease. In this study, they found that UTI was the most common source of SBI (prevalence 15-94%) whereas bacteremia was less common (prevalence 0-41%) and meningitis even more rare (prevalence 0-26%).

This infant is ill, but non-toxic and represents a clinical and diagnostic dilemma. A slightly red tympanic membrane in the setting of a crying, febrile infant is not representative of acute otitis media. The current evidence supports multiple

approaches – but only if the infant is well appearing. Doing “nothing” isn’t an option – but in general, WELL appearing babies can get blood and urine studies alone.”

Does this child need a lumbar puncture?

“This is a question that is dependent on your overall plan for the child. In Baker’s study (Philadelphia, 1993), 1.2% of patients had bacterial meningitis. However, etiologies of meningitis in these cases included Haemophilus influenza b

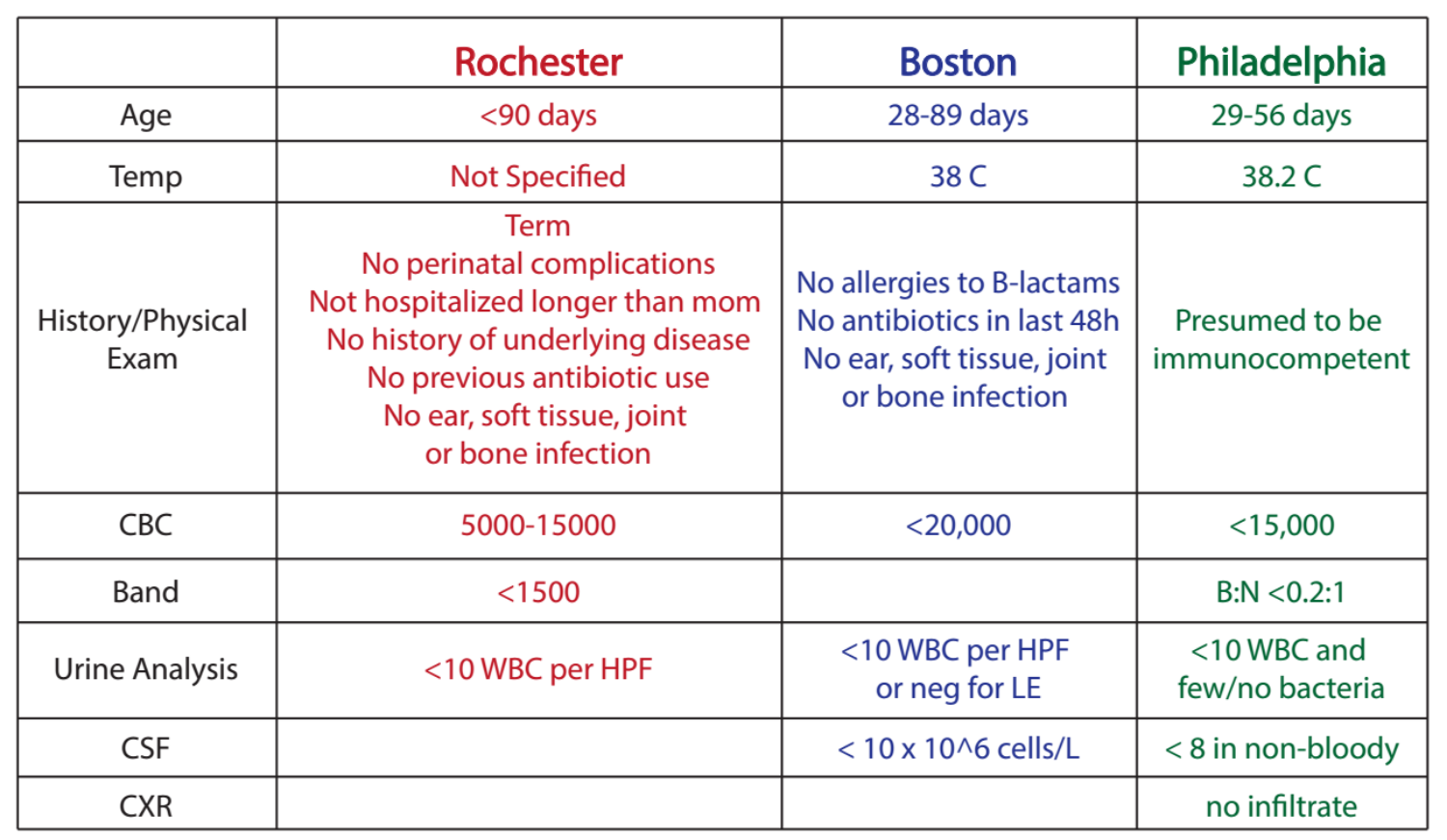

and Streptococcus pneumonia, both of which have become increasingly less notable players in invasive bacterial disease given the overall success of vaccine initiatives. More recently, bacterial meningitis is being cited at a prevalence of 0.3% in this age group. See Table 1 for features of infants at low risk for meningtis.

A study by Paquette et al. in 2011 looked retrospectively at 392 infants between 30 and 90 days with abnormal urinalyses, finding that only 4 ultimately had meningitis (1%). That being said, none of them were “well-appearing” on presentation nor met “low-risk” criteria. In 2010, Mintegi et al. retrospectively reviewed 685 cases of SBI evaluation in infants < 3 mos of age. In their study, the incidence of bacterial meningitis was 0.3%, all of which were identified by a combination of laboratory data and clinical appearance. Four infants (0.6%) who did not initially have an LP were ultimately diagnosed with aseptic meningitis, and all four did well.”

Table 1: Features and work-up results of infants who are at low risk of meningitis

Should you decide to do an LP, it will undoubtedly take a while to perform as you’re ED is full and your nurses and techs are already stretched thin. When, if ever, should empiric antibiotics started? What antibiotics should be given?

“Empiric antibiotics can be delayed until studies are obtained in the mildly-ill or well-appearing febrile neonate or infant. Only start empiric antibiotics on the aforementioned patient if you get an LP. Ceftriaxone or Cefotaxime would suffice. If there is pleocytosis on the CSF or a positive gram stain consider adding Vancomycin for Staph coverage and Acyclovir for HSV. If you are worried about HSV send a CSF PCR along with hepatic profile (may show transaminitis which is a clue to invasive HSV disease) along with swabs of skin, mucous membrane and eyes for PCR. Get an enterovirus PCR if it is the right season (August-October).”

If everything comes back normal what is the most appropriate disposition if there is still concern for SBI? Discharge with close PCP follow up? Admit and wait on culture results?

“If our patient was still “low risk” following completion of our work up, then there is still a decision to make. For this specific child, if you obtained blood and urine and low-risk criteria were met, plus a negative chest xray if ordered then you can consider discharge home. The patient should be consolable and have an improved HR with defervescence. They should also be able to feed. It is your job as the Emergency Department physician to ask the following questions: What are the family’s concerns? Will they be able to follow up tomorrow? Is it a holiday or weekend? Is the Primary Care Provider’s office even open? Is their PCP comfortable with them going home? Would the parents be more comfortable in the hospital? On antibiotics (after LP, of course)? You can admit off antibiotics LP or not. Again, any infant that gets antibiotics in this age range should be admitted 100% of the time.”

Low risk criteria for SBI broken down by original study

The patient has rhinorrhea and some scant wheezing at the right lung base. However, your suspicion of bacterial pneumonia is low. What is the utility of an CXR in this patient? You foresee a hedge read from the radiologist of atelectasis vs pneumonia? What are the chances that this patient has a bacterial pneumonia that will benefit from antibiotics?

“The most pertinent question is: What is your pretest probability that the patient does, in fact, have a clinical pneumonia? If you are more suspicious of early bronchiolitis, then the evidence would suggest that a CXR is not necessarily indicated and will result in a 12% greater likelihood that you will prescribe antibiotics when you don’t necessarily need to. The focal wheezing in the right lower lobe should be confirmed with a repeat examination after the infant is suctioned, cries and/or coughs. Focal lung findings in the febrile neonate, especially those with respiratory symptoms should prompt ordering of a chest radiograph.

It’s tough to use the risk-stratifying studies to identify the frequency of pneumonia as a source of SBI for two reasons: 1. Pneumonia usually presents with symptoms... 2. Therefore, pneumonia was not categorized as a SBI in many prior studies. However, Baker (Philadelphia, 1993) does note that 3.7% of the patients in his study of 747 infants between 29 and 56 days were ultimately diagnosed with pneumonia, despite none of these patients being in the SBI category. In Hui’s meta-analysis noted above, between 1-2% of patients in several of the studies cited had pneumonia. So, the true value may lie somewhere between 1-4%, however most of these infants are not asymptomatic.

All that considered, in a patient who has reassuring lab findings, improved clinical appearance with defervescence, and mild to no respiratory findings and without a persistent focal finding on examination, you might consider omitting a chest x-ray from your work up.”

Might a normal ANC and Procalcitonin level indicate a low enough risk of meningitis that we can forgo the LP?

“There’s a lot of interest in inflammatory markers to aid in the evaluation of SBI in young infants. While Gomez et al. (2012) found an elevated procalcitonin (PCT, > 0.5) to be associated with invasive bacterial disease, meaning either meningitis or bacteremia, with a OR of 22 (95% CI 8-57), England et al. (2014) found that it did not perform as well as current clinical prediction models. Yo et al. (2012) performed a meta-analysis including 1883 patients < 3 mos with fever which suggested that elevations in either PCT or CRP have better sensitivities than WBC counts, however specificities are similar, drawing the authors to conclude that these studies are better at ruling out disease – counter to what England suggests. Moreover, the LRneg for PCT and CRP are 0.25 and 0.35, respectively, which doesn’t strikingly change your pretest/posttest probability. Interestingly, Nabulsi et al. (2012) note that there are few indications for inflammatory marker testing that are truly “evidence based”, that most providers tend not to use them in an evidence-based fashion, and that they infrequently inform medical decision making. ”

A special thank you to Dr. Benjamin Ostro, PGY-4 Emergency Medicine Resident at University of Cincinnati Medical Center, for facilitating this discussion and Dr. Brad Sobolewski, Assistant Professor in Pediatric Emergency Medicine at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, and Dr. Adam Vukovic Clinical Fellow in Pediatric Emergency Medicine at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, for participating in our expert commentary. Be sure to check out Dr. Brad Sobolewski's PEM Blog for more pediatric emergency medicine FOAM.

References

Andreola, B., Bressan, S., Callegaro, S., Liverani, A., Plebani, M., & Da Dalt, M. Procalcitonin and c-reactive protein as diagnostic markers of severe bacterial infections in febrile infants and children in the emergency department. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 26(8), 672-677.

Baker, M. D., Bell, L. M., & Avner, J. R. (1993). Outpatient management without antibiotics of fever in selected infants. The New England Journal of Medicine, 329(20), 1437-1441.

Baskin, M. N., O’Rourke, E. J., & Fleisher, G. R. (1992). Outpatient treatment of febrile infants 28 to 89 days of age with intramuscular administration of ceftriaxone. Pediatrics, 120(1), 22-27.

Bilavsky, E., Yarden-Bilavsky, H., Ashkenazi, S., & Amir, J. (2009). C-reactive protein as a marker of serious bacterial infections in hospitalized febrile infants. Acta Pediatrica, 98, 1776-1780.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Progress toward elimination of Haemophilus influenzae type b invasive disease among infants and children—United States, 1998-2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51(11):234-237.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Invasive pneumococcal disease in children 5 years after conjugate vaccine introduction—eight states, 1998-2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly ep. 2008;57(6): 144-148.s

Dagan, R., Powell, K. R., Hall, C. B., & Menegus, M. A. (1985). Identification of infants unlikely to have serious bacterial infection although hospitalized for suspected sepsis. Pediatrics, 107(6), 855-860.

England, J. T., Del Vecchio, M. T., & Aronoff, S. C. (2014). Use of serum procalcitonin in evaluation of febrile infants: A meta-analysis of 2317 patients. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 47(6), 682-688.

Gomez, B., Bressan, S., Mintegi, S., Da Dalt, L, Blazquez, ... , & Ruano, A. (2012). Diagnostic value of procalcitonin in well-appearing young febrile infants. Pediatrics, 130(5), 815-822.

Hamilton, J. L., & John, S. P. (2013). Evaluation of fever in infants and young children. American Family Physician, 87(4), 254-260.

Hui, C., Neto, G., Tsertsvadze, A>, Yazdi, F., Tricco, A. C., ..., & Daniel, R. Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 mos). Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2012, Mar. (Evidence Report/Technology Assessment, No. 205)

Mintegi, S., Benito, J., Astobiza, E., Capape, S., Gomez, B., & Eguireun, A. (2010). Well appearing young infants with fever without known source in the emergency department: Are lumbar punctures always necessary? European Journal of Emergency Medicine, 17 (abstract).

Nabulsi, M., Hani, A., & Karam, M. Impact of c-reactive protein tewst results on evidence-based decision-making in cases of bacterial infection. BMC Pediatrics, 12(140), 1-7.

Paquette, K., Cheng, M. P., McGillivray, D., Lam, C., & Quach, L. (2011). Is a lumbar puncture necessary when evaluating febrile infants (30 – 90 days of age) with an abnormal urinalysis? Pediatric Emergency Care, 27 (11), 1057-1061.

Yo, C., Hsieh, P., Lee, S., Wu, J., Chang, S., ... , & Lee, C. (2012). Comparison of the test characteristics of procalcitonin to c-reactive protein and leukocytosis for the detection of serious bacterial infections in children presenting with fever without source: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 60(5), 591-600.